If Malaysia’s political impasse breaks, the impact may be global.

“I myself have never wanted foreign interference in our domestic affairs,” former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad declared in late June in his Putrajaya office. “But domestic means of redress have been closed.”

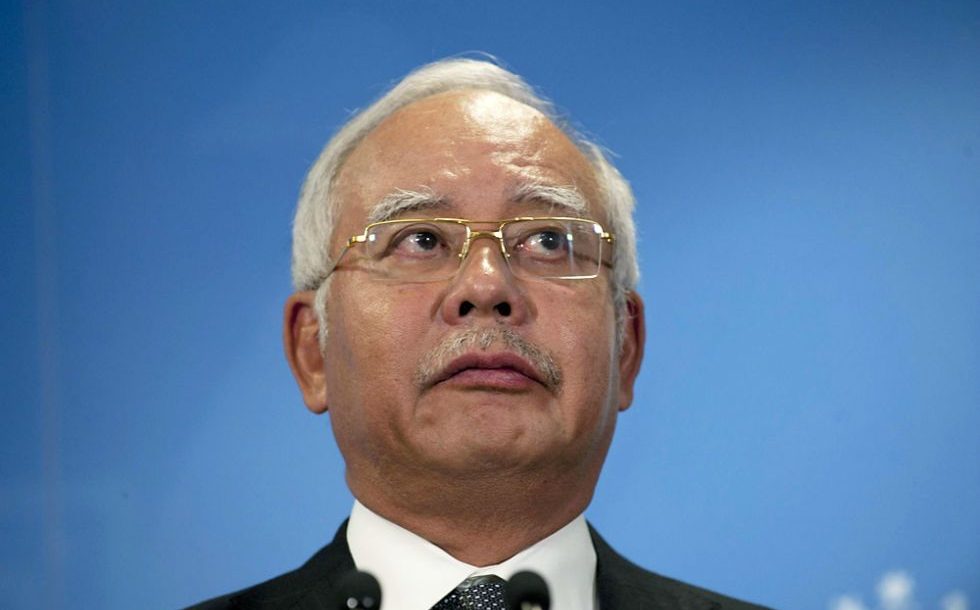

Since I spoke to him then there’s been much debate between Malaysia analysts on whether current PM Najib Razak’s position is safe, and how much longer he can hold on before the cluster of problems now assembled around him ends his political career. Today, the ANU Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs hosts the 2016 Malaysia Update largely focused on this debate.

This is an important question, not only for Malaysia but for Australia. Analysts in Asia continue to argue that Najib is unassailable, based on their analysis of formal UMNO structures and the Malaysian bureaucracy. Mahathir largely concurs in his assessment of Najib’s domestic prospects, saying “the AG [Attorney-General] will not take up the case against him in the court.

“The AG simply brushes aside all reports, just like 1MDB,” the state development fund that the United States Department of Justice (DoJ) is now investigating under its Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative. “So he will never be proven guilty because the courts are under his control,” Mahathir adds.

Nevertheless, DoJ documents have named Najib’s step-son Riza Aziz, financier Low Taek Jho (or Jho Low), his associate Eric Tan, along with two government officials in Abu Dhabi. The DoJ believes that USD $3.5 billion was siphoned out of the fund, of which it claims that $1 billion was laundered through the purchase of US-based assets or “dissipated” through lavish lifestyle expenses.

The DoJ announcement makes clear that the international reach of the Najib saga—now creating many problems for Malaysia’s trading partners—makes external jurisdictions the key arena in which Najib’s opponents are now moving to depose him. Yet precisely because the networks, relationships and Machiavellian stand-offs now operating around Najib are too numerous and diffuse, there remains no telling how long he will last, or, importantly, what change will follow if sufficient forces combine to push him.

The problem is nevertheless now affecting elites at the highest level in the United States, where the scandal has reached Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. Leonardo Dicaprio, star of Wolf of Wall Street and potential beneficiary of 1MDB funds through Riza’s company Red Granite Productions, has had to drop out of hosting a Hollywood fundraiser he planned to hold for her. It has also prompted action in Switzerland and Singapore, which have acted against banks and account holders in their jurisdictions that have links with 1MDB.

In Australia, the government has stayed relatively quiet on 1MDB, although Foreign Minister Julie Bishop has finally noted publicly that the allegations against Najib are “serious”. Mahathir, however, argues that the government is out of step with Australians’ attitudes.

“There is a dichotomy in Australia between the people and the government,” Mahathir said. “On the one hand, the people are aware of what’s happening in Malaysia. They have been here, they know Malaysia, and some of them were Malaysians.”

“But your government,” Mahathir continued, “is not willing to confront the Malaysian government.”

“Australian TV have come out with a lot of things,” Mahathir noted, “but the government is being very clinical.”

Indeed, in open forums this might be genuinely difficult. Key regional relationships are built around Malaysia’s political stability, built around a strong volume of trade, migration and regular elections that have delivered victory to Najib’s government since 1957. Now, the words “Malaysia Solution” have even returned to national public debates around refugees and asylum-seekers, and counter-terrorism and other security relationships also depend on Malaysia as a key regional partner.

Yet Najib’s opponents also have excellent international access, which, in Australia for example, has only gained them more influence since the 2013 election result, in which the opposition parties won the popular vote. For some time now in Australia, not a month has passed without representatives of the PKR, the People’s Justice Party led by Anwar Ibrahim, visiting academics, officials, politicians, community supporters, and their friends and relatives in Australian cities.

Mahathir too has allies travelling overseas. One of these allies, Ibrahim Ali, who is head of Malay nationalist organisation Perkasa, which Mahathir advises, is in Canberra today for the ANU Malaysia Update. Ibrahim has recently announced he will consider joining the new party that Mahathir is setting up, called Parti Pribumi Bersatu (PBB)—United Natives this time, as distinct from United Malays.

In Malaysia, the PBB is negotiating with the PKR and its allies over how best to collaborate electorally to oust UMNO at the 2018 election. Mahathir’s credentials as a Malay nationalist are a useful support for his pitch to disproportionately powerful rural seats dominated by Malay Muslims, and his social media channels are actively calling on UMNO members to defect to him.

Yet these negotiations are sticky and problematic. Mahathir must avoid being damaged by racially-charged allegations that he is in league with Malaysia’s ethnic Chinese, and he will also need to find a way to address the rift between him and Anwar Ibrahim, who was imprisoned for five years in 1999 on charges of corruption after a lengthy and damaging trial for sodomy.

He will also need to avoid being tainted by allegations that he is working with foreign imperialists, as Najib and his allies have begun a strong nationalist campaign at home, insinuating that Western powers like the United States carry an anti-Muslim agenda that infects the DoJ investigation.

The last thing the Australian government needs is to be confronted with similar allegations. Yet it is now finding itself inexorably drawn in to the contest, due to awkward connections enabled by this nation’s very strong ties with Malaysia.

For example, Stephen Lee, a suspect under investigation for the recent murder of Sarawak PKR leader Bill Kayong has been tracked down in Australia, a logical place to flee given Australia will not extradite people at risk of being executed for capital crimes.

Australia’s Villawood detention centre is also now host to Sirul Azhar Umar, convicted murderer of Altantuya Shaarribuu, a Mongolian interpreter who assisted Malaysian negotiations with French submarine firm DCNS in 2002.

From time to time, speculation emerges in Malaysia as to when he will go public with allegations that Najib and his wife Rosmah ordered the murder, after Altantuya threatened to expose alleged kickbacks between Malaysian officials and the firm in question.

Sirul has already been sentenced to death in Malaysia for his part in the crime, while DCNS has since won a contract to build twelve Barracuda submarines for Australia, a project which has been touted as a victory for job creation in South Australia. DCNS built Malaysia’s Scorpene submarines, whose secret combat capability has been leaked in recent days.

Meanwhile, Mahathir-linked figure Matthias Chang has filed a class action on behalf of Malaysian citizens over 1MDB funds in the United States, supported by a group of Amanah Party leaders including Husam Musa, who are also seeking support for the suit from Malaysia’s King.

With every such move and countermove the Najib issue grows yet larger, and becomes yet more international in its scope. The political impasse remains in place, yet if and when a decisive shift suddenly results, it may set off a chain of events all over the world, including in Australia.

Calling a result or a timeline at this stage would involve pure speculation, and Australian researchers working on Malaysia would be better off combining forces to support Malaysians’ capacity for civic, political and institutional resilience through whatever change is about to ensue. I have made this case in more detail elsewhere.

Meanwhile, the race to internationalise the issue continues apace.

“If anything can be done outside the country,” Mahathir said, “we would welcome that. We are forced to.”

“I don’t care. They can take away my passport. They can watch me as much as they like.”

Amrita Malhi is a Visiting Research Fellow in the ANU Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs. Her website is www.amritamalhi.com.

This article is based on an in-depth interview between Amrita Malhi and Dr Mahathir Mohamad and is the final in a four-part series. Read the first, second and third. A shorter version of this article was also published in The Canberra Times.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss