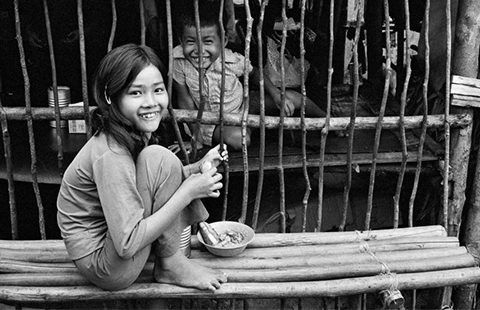

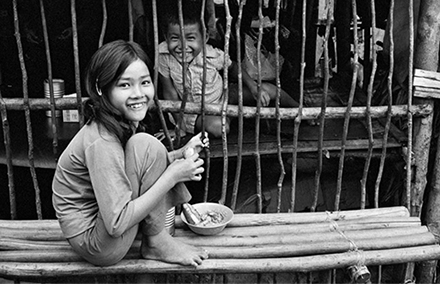

Vietnamese refugees at the Pulau Bidong refugee camp in Malaysia. UN Photo/John Isaac. www.unmultimedia.org/photo/

Aslam Abd Jalil – in the second of a three-part series – looks at how Malaysia’s lack of consistency is hurting asylum seekers.

For the past 40 years, Malaysia has been a major destination for refugees seeking either temporary or permanent refuge from devastating conflicts in the region and further afield.

This is despite the country not being a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol.

In the past, asylum seekers have included Filipino refugees from Mindanao arriving during the late 1970s and early 1980s, Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees during the 1980s and 1990s, a small number of Bosnian refugees in the early 1990s, and Indonesians from Aceh in the early 2000s.

Malaysia also continues to receive refugees from Myanmar’s troubled ethnic minorities, especially the stateless Rohingya. Unlike most of these Myanmar asylum seekers who arrive by crossing the Thailand-Malaysia border illegally, refugees from other regions like the Middle East and Africa board planes to Kuala Lumpur, as Malaysia practices a visa upon arrival system.

Clearly refugees are a major part of the nation’s day-to-day reality.

But currently, Malaysia has at best an ad hoc policy towards refugees and there is no clear and official plan from the Malaysian Government on how best to handle these groups.

To add to the confusion, despite not being a signatory to the UN refugee convention, Malaysia does allow for the presences of refugees in the country on the basis of humanitarian grounds, and cooperates with the UNHCR in addressing these issues.

Officially, Malaysia has strict immigration rules that prohibit illegal entry into the country and enacts severe punishment for anyone found guilty of doing so. However, the humanitarian grounds exception means that at certain times these rules are not enforced.

It is also important to note that by allowing these refugees to stay does not involve the state playing an active role in protecting them or their rights. Instead the UNHCR, since 1975, and other NGOs, including religious-based organisations, take up this function.

The major flaw of Malaysia’s current ad hoc refugee policy is that the government is trying to deny existing problems related to asylum seekers and refugees. It also causes greater uncertainty and confusion for all parties, especially the Malaysian authorities tasked with handling refugees.

Malaysia’s most successful policy in managing refugees came almost 30 years ago during its role in the international Comprehensive Plan of Action (CPA) for Indochinese Refugees.

A major flow of Vietnamese refugees to Malaysia (and the region more broadly) in the 1970s and 1980s led to the drafting of the CPA in Kuala Lumpur in March 1989 and its adoption at an international conference in Geneva in June that same year.

The international agreement was not only set up to stop the flow of boat people from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, but provided a framework for refugee status determination for these asylum seekers and their voluntary repatriation and resettlement to third countries.

Consensus was achieved between the countries of origin (in Malaysia’ case Vietnam), host countries of first asylum, including Malaysia, and third countries beyond the region. Under the agreement, Malaysia accepted around 250,000 Indochinese boat people who resided at Pulau Bidong refugee camp in Terengganu.

Malaysia managed to give temporary protection to the refugees at that time because of the coordination with third countries, and countries of origin. The refugees sheltered at refugee camps in Malaysia were processed to determine their refugee status.

Once they were proven to be genuine in fleeing persecution, third countries such as Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom, and European states resettled them. As for the non-refugees, Vietnam was willing to accept their voluntary return.

The international consensus between different countries and the leadership of the UNHCR were key factors in this successful example of “burden sharing” in solving the major refugee issue at that time.

Since the plan ended on 6 March 1996, there has been no more comprehensive multilateral agreements regarding the issue.

With so much uncertainty and inconsistency caused by current policy, and with so many refugees living in limbo, perhaps it is time for Malaysia to revisit a comprehensive and multilateral approach to the movement of asylum seekers in the region.

Aslam Abd Jalil, is a graduate of the Australian National University, and a refugee rights campaigner.

This is the second article in a three-part series on Malaysia’s treatment of refugees and asylum seekers. Read the first article here.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss