Few figures in modern history have attracted as much biographical attention as Myanmar’s State Counsellor and de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi. The Griffith Asia Institute’s select bibliography of Burma (Myanmar) Since the 1988 Uprising, the third edition of which was published earlier this year, lists 34 books in English about her, all written since 1990. There are several others, in other languages, and even a few collections of photographs. Most have been aimed at the general public, including young readers. All of these books were written after Aung San Suu Kyi became an icon of democracy, adored by millions and held up by the international community as a paragon of virtue, the result of her long struggle for universal human rights and peaceful democratic change. Very few biographies have appeared since her government took office in 2016, and she was in a position to give practical effect to her ideas about political, economic and social reform. As a result, the world has been waiting for years for a study that rigorously and objectively examines not just the Nobel Peace laureate’s undoubted strengths and achievements, but also her weaknesses and policy failures.

Few figures in modern history have attracted as much biographical attention as Myanmar’s State Counsellor and de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi. The Griffith Asia Institute’s select bibliography of Burma (Myanmar) Since the 1988 Uprising, the third edition of which was published earlier this year, lists 34 books in English about her, all written since 1990. There are several others, in other languages, and even a few collections of photographs. Most have been aimed at the general public, including young readers. All of these books were written after Aung San Suu Kyi became an icon of democracy, adored by millions and held up by the international community as a paragon of virtue, the result of her long struggle for universal human rights and peaceful democratic change. Very few biographies have appeared since her government took office in 2016, and she was in a position to give practical effect to her ideas about political, economic and social reform. As a result, the world has been waiting for years for a study that rigorously and objectively examines not just the Nobel Peace laureate’s undoubted strengths and achievements, but also her weaknesses and policy failures.

The Daughter: A Political Biography of Aung San Suu Kyi, by long time Myanmar-watcher Hans-Bernd Zöllner and freelance journalist Rodion Ebbighausen, is a comprehensive and thoughtful account of her life and times, and ventures into a few unfamiliar areas, but it still does not satisfy that need.

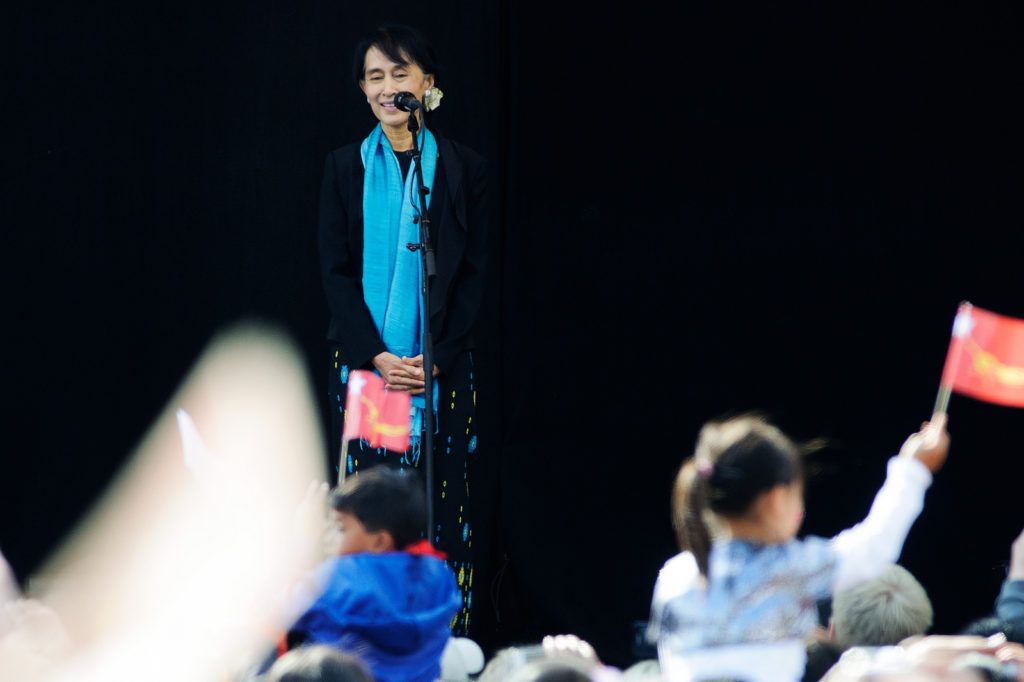

Before 2016, Aung San Suu Kyi was not just admired, she was idolised. Wherever she went, both within Myanmar and outside it, she was given what journalists liked to describe as “a rock star welcome”. This cult of personality helped her become a household name around the world and boosted her cause, but it had a downside. In journalistic and even academic circles she was rarely subjected to the same level of critical analysis as other world figures, or members of the military government she opposed. When more objective Myanmar-watchers dared to point out examples of her poor judgement and tactical missteps, or suggested that, like everyone else, she had flaws in her character, they were subject to an avalanche of abuse. One outspoken critic who wrote disparagingly about The Lady (as she became widely known), and the tunnel vision of her more extreme supporters, was sent a death threat. This had the effect of silencing many commentators aware of her imperfections, or who disagreed with some of her decisions. Even professional analysts began to self-censor what they wrote about her.

To be fair, they did this not just out of fear of being attacked by Aung San Suu Kyi’s legion of supporters, who used the Internet and social media to great effect. Serious observers of Myanmar were aware that to openly criticise Aung San Suu Kyi risked giving the military regime ammunition to use against her. For years, a virulent campaign was waged against the opposition leader in the state-run news media, where she was cast as a traitorous renegade who had turned her back on her own people. Countless stories and cartoons, including jibes about her marriage to a foreigner and her schooling abroad (in India and the UK) were published with the aim of undermining her popularity with the Myanmar people. Anything written by foreign commentators in the international press, or said by them in public, that could be used to support the regime and bolster its case against Aung San Suu Kyi, was seized upon and shamelessly exploited. With that danger in the back of their minds, more critical and aware foreign observers tended not to draw attention to her shortcomings as an alternative leader of Myanmar.

Doubtless, in private counsels and confidential reports prepared for senior officials, diplomats and strategic analysts took a hard-headed approach and produced unvarnished assessments of Aung San Suu Kyi’s character, political skills and suitability for high office. Presumably, they also warned that, should she ever find herself in a position of real power, she would inevitably be forced to choose sides between contending factions, and make hard decisions about contentious issues, in ways that would leave some of her admirers dissatisfied. She would not be able to please everyone, or avoid controversy, simply by referring to broad principles and abstract concepts, as was her usual practice. However, for obvious reasons, the recipients of such assessments were unlikely to share them with the public. Some senior officials (George W. Bush and Gordon Brown spring to mind) may have even been reluctant to accept them. Thus the net effect of the world-wide campaign being waged on her behalf was to strengthen the popular image of her as being without fault or peer, existing above the grubby political fray.

This two-dimensional picture was reflected in most of the books written about her. As Kyaw Yin Hlaing pointed out in a review article, “Quite often the biographies of leading political figures are written by their loyalists, enemies, or by neutral authors or scholars. In the case of Suu Kyi, however, one finds that most of the writings about her are written by her sympathisers and her enemy (the Myanmar junta)”. Works in the former category were not all hagiographies. For example, Bertil Lintner’s Aung San Suu Kyi and Burma’s Struggle for Democracy discussed some of the criticisms usually levelled at The Lady. Other books made passing references to Aung San Suu Kyi’s human frailties and some other perceived shortcomings. However, these character flaws tended to be brushed over as insignificant in the greater scheme of things. As a rule, very few authors attempted to offer an objective picture of the opposition leader that stripped away her public image to show the real person underneath, warts and all. As Barbara Victor wrote in her own biography, titled The Lady, “deconstructing Aung San Suu Kyi is not part of the game”.

Aung San Suu Kyi in Oslo, 2012 (Photo: aktivioslo on Flickr, Creative Commons

Over the past few years, however, the pendulum has swung completely the other way. Aung San Suu Kyi is now being lambasted by the international community and, albeit to a much lesser extent, criticised by many people within Myanmar. At one level, this is hardly surprising. Her government has disappointed on several fronts, failing to deliver on most if not all the promises she made before the 2015 elections. Given the challenges she inherited, and the unrealistic expectations held about her ability to solve Myanmar’s “fiendishly complex problems”, that was to be expected. However, her dramatic fall from grace in the eyes of the international community has come about mainly because of her response—or lack of it—to the Rohingya crisis of 2016–2017, which saw three quarters of a million Muslims driven into Bangladesh by Myanmar’s security forces in circumstances that have been labelled by the UN ethnic cleansing, if not genocide. She has also publicly defended egregious human rights violations in other contexts.

Aung San Suu Kyi is now the subject of vitriolic abuse in the international news media. Amnesty International recently stripped her of its highest honour, telling her that “you no longer represent a symbol of hope, courage and and the undying defence of human rights”. There have even been calls for her Nobel Peace Prize to be rescinded.

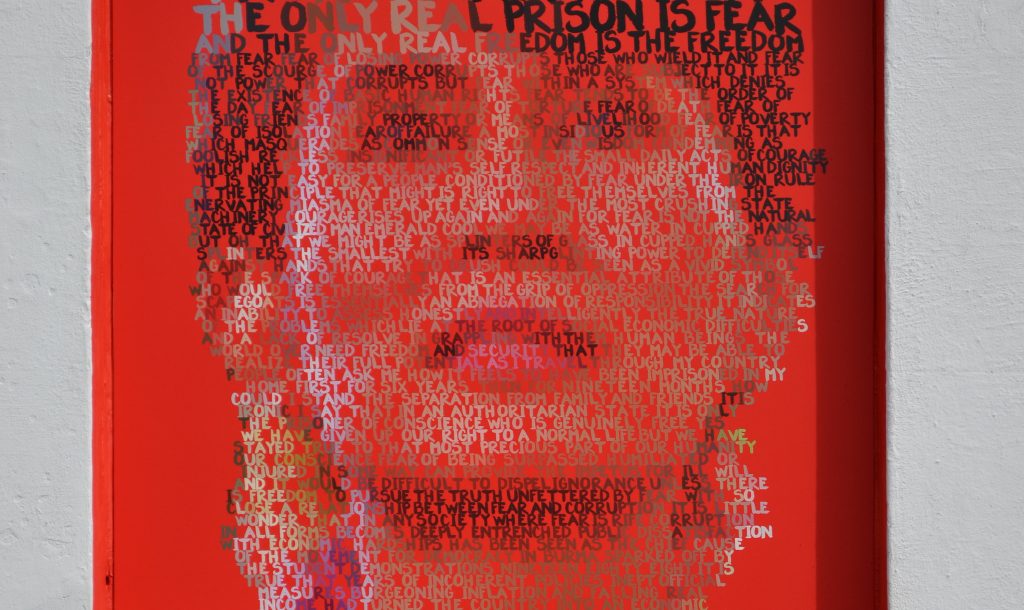

The collapse of Aung San Suu Kyi’s international reputation, and the flight of her former high profile supporters, begs for a detailed explanation. Also, the apparent abandonment of her principles on universal human rights, and her rejection of the international community’s responsibility to protect the vulnerable in countries like Myanmar, warrants close examination. Her current position is in stark contrast to the well-publicised views she held as a political prisoner. While at one level the picture is clear, these issues can be quite complex, and in certain cases her actions may appear less reprehensible when put into a wider context. For example, Aung San Suu Kyi has no control over the actions of Myanmar’s armed forces (Tatmadaw) which, under the 2008 constitution, act independently of her quasi-civilian government. Similarly, on the Rohingyas, there is a rare consensus between the government, the armed forces and the wider population that may restrict her freedom of action. This is not to offer any excuses, simply to emphasise the need for a thorough and objective account of her policies and personal attitudes.

Hans-Bernd Zöllner is in a good position to offer informed comments on such matters. He is an accomplished Myanmar-watcher, with several major works to his name. To English-speakers, he is perhaps best known for his compilations of Aung San Suu Kyi’s speeches and informal comments to her followers, published as Talks Over the Gate: Aung San Suu Kyi’s Dialogues with the People, 1995 and 1996. He has also written a history of the conflict between Aung San Suu Kyi and the Tatmadaw, set in a global context. Another work of note is his chapter comparing different accounts of the 1988 pro-democracy uprising, published in Volker Grabowsky’s edited volume Southeast Asian Historiography. Rodion Ebbighausen is not well-known in English-speaking countries as a Myanmar-watcher, but he is an experienced journalist who has covered the country for Deutsche Welle and other news outlets. He has also written occasionally about Aung San Suu Kyi, most recently in connection with the Rohingyas.

So, what have these two experienced observers made of Aung San Suu Kyi’s political career and her performance since she achieved her life-long ambition to become Myanmar’s (de facto) ruler?

Rohingya identity and the limits to history

The discussion around the history of the Rohingya, at its worst, deflects attention away from the problem of defining citizenship through ethnic indigeneity.

This narrative is well told and covers all the main bases, but is curiously flat. The book goes over a lot of familiar ground, but offers little by way of new information or original analyses of critical events. Given everything that has already been written about Aung San Suu Kyi, this was perhaps inevitable to a certain extent, but the reader is left wondering why the authors have not addressed more directly and in greater depth the criticisms made of Aung San Suu Kyi during her political career. Despite the general reluctance to highlight her shortcomings, commentators have referred to such personality traits as her profound sense of personal destiny, her aloofness (or arrogance), her refusal to accept criticism or to countenance dissent, her dismissal of potential rivals, and her reluctance to include activists like the 88 Generation Students Group in the wider pro-democracy movement. Nor have the two authors critically examined her encouragement before 2011 of tough economic sanctions against Myanmar and her opposition to tourism, despite the negative impact these policies clearly had on the wider population.

Perhaps the most disappointing aspect of this book, however, is its failure to take the opportunity to look closely at Aung San Suu Kyi since she took political office. She has been criticised for vetting all bills herself and taking all important decisions on both party and government matters. She has reportedly surrounded herself with a small group of loyalists, and does not consult others who could offer different advice. These practices have caused serious problems in the conduct of government business. More particularly, her attitude towards the ethnic communities has been described as both imperious and unsympathetic, encouraging the view that, at heart, she is an ethnic Burman centralist who shares the Tatmadaw’s hard line towards minority groups, including the Muslim Rohingyas. Indeed, over the past few years she appears to have made little attempt to curb the blatant misuse of power by the security forces and judicial system. These are all matters that would have benefited from a rigorous and balanced analysis, both to put the record straight where it has strayed from the truth, and to help explain what appears to many people to be a puzzling about face on the part of someone they once admired.

Zöllner and Ebbighausen have said that they are keen to provide a nuanced portrayal of Myanmar’s crises over the past 30 years, with Aung San Suu Kyi as a focal point. They have succeeded in this aim, but failed to meet the not unreasonable expectation that Aung San Suu Kyi would be examined more critically, now that she has revealed herself to be a more complicated person than was once portrayed. Her elevation to the leadership of Myanmar, and the challenges that she has faced in that role, has required qualities that seem to be lacking. As former US ambassador to Myanmar Derek Mitchell has written, “Opposing oppressive state power and running a government are two vastly different skills”. There were bound to be teething problems, and grumbles at the slow pace of change. Also, the 2008 constitution was going to require compromises. However, few people expected that Aung San Suu Kyi would become the target of such bitter invective, mostly from the same foreigners and foreign institutions which had once idolised her.

Myanmar has always been much more complex than popularly portrayed, and Aung San Suu Kyi has been subject to as many myths and misconceptions as other aspects of the country’s modern history. Had Zöllner and Ebbighausen written more about the controversies and criticisms now associated with The Lady, and tried to explain them in greater depth, they would have produced a more interesting book, and one that made a greater contribution to the burgeoning literature on modern Myanmar.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss

Dr Andrew Selth is Adjunct Associate Professor at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University, and at the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, Australian National University. He is the author of

Dr Andrew Selth is Adjunct Associate Professor at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University, and at the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, Australian National University. He is the author of