One of the bigger shortcomings of the field of Vietnamese Studies over the past generation or so is its failure to produce a comprehensive or authoritative account of the historical phenomenon known as Renovation (Doi Moi). Whether conceived of as liberalising policy orientation introduced by the party-state at the 6th Party Congress or as a reformist zeitgeist that took hold inside the country during the late 1980s, Renovation has clearly been a critical force in Vietnamese economic, political, cultural and intellectual life for over thirty years.

Nevertheless, foreign scholars interested in the topic have tended to focus narrowly on parts of Renovation while neglecting to consider the whole. When students ask me for readings on Renovation, I tend to recommend the work of Adam Fforde on economics, Carlyle Thayer on politics, Tuong Vu on ideology, Ben Kerkvliet on agriculture, Hy Van Luong on village culture, Pam McElwee on environmental politics, Nguyen Vo Thu Huong on gender relations, John Schafer on literature and so on. But it’s much more difficult to identify a single article, book or scholar that provides an integrated overview of Renovation—one that includes a history of its origins, a discussion of its evolution over time and an accounting of its uneven impact in multiple spheres of Vietnamese life.

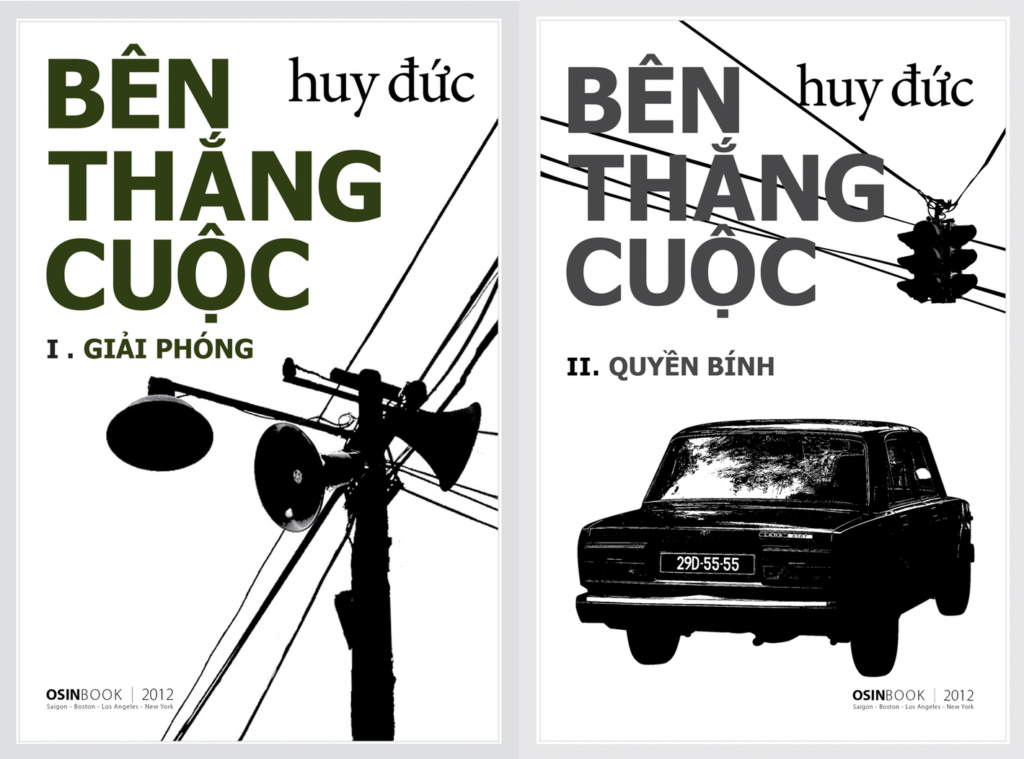

Among its many accomplishments, Huy Đức’s book The Winning Side—published in two volumes in Vietnamese under the title Bên Thắng Cuộc—provides the best account available in any language of the history and significance of Renovation. It offers a thorough consideration of the domestic crisis that generated social demand for far-reaching reforms during the decade following the conclusion of the 2nd Indochina War. It narrates the “one-step-forward-two-steps-backward” process whereby the reforms were implemented. Finally, it describes the reasons for the premature short-circuiting of the reform agenda, especially in the cultural and political spheres. In short, The Winning Side offers a panoramic view of Renovation—one that reveals and explains its successes and failures.

Among its many accomplishments, Huy Đức’s book The Winning Side—published in two volumes in Vietnamese under the title Bên Thắng Cuộc—provides the best account available in any language of the history and significance of Renovation. It offers a thorough consideration of the domestic crisis that generated social demand for far-reaching reforms during the decade following the conclusion of the 2nd Indochina War. It narrates the “one-step-forward-two-steps-backward” process whereby the reforms were implemented. Finally, it describes the reasons for the premature short-circuiting of the reform agenda, especially in the cultural and political spheres. In short, The Winning Side offers a panoramic view of Renovation—one that reveals and explains its successes and failures.

The Winning Side locates the origins of Renovation in a self-inflicted crisis that beset Vietnam during the post-war decade from 1975–1986. The crisis included seven critical elements presented by Huy Đức in seven discrete chapters: (1) the extra-judicial confinement in horrible conditions of hundreds of thousands of southern Vietnamese in re-education camps following the end of the War; (2) the effort by the Vietnamese party-state to repress members of the southern bourgeoisie, to shut down or nationalise their businesses and to confiscate their wealth; (3) the persecution by the party-state of the country’s resident Chinese population— initially this policy was one component of the attack on the southern bourgeoisie but later it accelerated as part of a separate campaign to eliminate a “fifth-column” within Vietnamese territory during the county’s border war with China; (4) the Vietnamese army’s invasion and occupation of Cambodia starting in 1978; (5) the exodus over sea and land of hundreds of thousands of migrants who fled Vietnam during the late 1970s and early 1980s in the hopes of escaping communist rule and resettling abroad; (6) an official government effort to transform southern Vietnam through the repression of “decadent” southern culture—measures employed in this effort included book burnings, the banning of “reactionary authors,” the policing of clothes, fashion and hairstyles, the imposition of a strict regime of censorship over the fine arts and the introduction of affirmative action for the children of labourers and revolutionaries and a regime of discrimination for those whose families worked for the old southern government; and (7) the effort by the victorious North to impose a deeply inefficient socialist economic system on the defeated South.

One of the most remarkable aspects of The Winning Side is the extraordinary frankness of this section of the book especially given the fact that it was written by a working journalist based inside the country. Huy Đức describes how communist officials lied baldly and repeatedly about the duration of re-education. He depicts how family members were encouraged to turn in their relatives. He details the appalling conditions in the camps and the callous mistreatment of inmates’ families. He portrays the anti-bourgeois crusades and anti-Chinese operations as rapacious campaigns of official theft, extortion and coercive expulsion. His account of the Cambodian invasion emphasises the irony of the Vietnamese Communist Party’s close historic relationship with Pol Pot. His depiction of the massive post 1975 migration reveals the role played by corrupt local security forces in facilitating and profiting from the exodus. And he pulls few punches in his account of the catastrophic “Northification” of the southern Vietnamese economy, a campaign driven by a mix of arrogance, stupidity and ideological zeal.

Huy Đức blames Le Duan for “Northification” but he implicates Ho Chi Minh as well by juxtaposing a discussion of the policy (in Chapter 8) with an extended digression called “Uncle’s Road” (Con Đưưng Cưa Bác). In “Uncle’s Road,” Huy Đức describes Ho Chi Minh’s endorsement of the communisation of the northern economy during the 1950s—a policy that included the notorious Land Reform of 1953–56 as well as an assault on the northern bourgeoisie that provided a precedent for the attack launched against this class in the South after 1975. Here, Huy Đức goes beyond an increasingly common interpretation of Vietnamese communist politics during the 1950s and 60s—an interpretation favoured in Ken Burns’ recent documentary film— that pits a radical Le Duan against a moderate Ho Chi Minh.

Huy Đức is not the first writer within the country to mention these unpleasant aspects of postwar Vietnamese history. But it is striking how his account eschews the normal style favoured by in-country Vietnamese writing—a style marked by euphemism and patterned understatement. Still, the point I want to underline here is that Huy Đức’s account of the post-war crisis is important not just for its candour and explicitness but for the way that it helps to explain the emergence of the Renovation policy in the mid-1980s.

As with his description of the crisis that provoked Renovation, Huy Đức’s narrative of the reform process includes a complex series of elements. These include: (1) an account of unsanctioned experiments with private enterprise—known as fence-breaking—that were attempted in several localities during the late 1970s and that produced levels of growth and dynamism that contrasted with the malaise and inefficiency of Vietnam’s socialist economy; (2) an account of the gradual embrace of these experiments by party leaders at the 6th Party Congress; (3) an account of the withdrawal of Vietnamese troops from Cambodia as part of an effort to create more favourable international conditions for Vietnam to expand and consolidate its economic reforms; (4) an account of partially successful efforts in the late 1980s to extend the spirit of the economic reforms to the cultural and intellectual realms through the liberalisation of the media and the easing of censorship over the fine arts, and (5) an account of failed efforts to extend the spirit of the reforms still further to the political sphere through the advocacy of forms of pluralism and multi-party democracy.

While the crisis of 1975–86 provides the broadest context for the emergence of Renovation described in this part of the book, Huy Đức points to a range of additional factors that shaped the adoption of the reform agenda.

One such factor was the emergence of a new global environment that was unusually hospitable to the Vietnamese reforms. This environment included the rise of reformist leaderships in China and the Soviet Union, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the end of aid from socialist allies, the willingness of multilateral and non-governmental organisations to provide critical developmental assistance, and an improved diplomatic climate regarding ASEAN, the EU and the United States.

Another factor was a longer history of economic reform and indigenous entrepreneurship that provided a tradition upon which economic Renovation might build. Here, Huy Đức describes the significance of Kim Ngoc’s experiments with a “household contract system” in Haiphong in the 1960s as well as early fence-breaking efforts in Long An province spearheaded by Bui Van Giao and Nguyen Van Chinh in the 1970s. In Chapter 16, he digresses about the careers of successful Vietnamese entrepreneurs like Bach Thai Buoi during the colonial era and about the perseverance of the resourceful Vietnamese silk magnate Trinh Van Bo during the first Indochina War and the early days of socialist construction in the North.

These examples prefigure the autonomous rise of successful petty businesses in the South prior to Renovation involving rain-coat patching, ink-pen refilling, sandal recycling, cigarette rolling and soapmaking. The data presented here provides a nice counterpoint to the section on the global context by showing how reformist energy built upon an older indigenous foundation. It also suggests that the development of a market economy in the 1980s involved the re-learning of dormant habits-of-mind rather than the wholesale development of these habits from scratch.

While the obvious hero of The Winning Side is the arch-reformer Vo Van Kiet, the most unexpected advocate for Renovation is Truong Chinh. His change of mind from conservative Marxist-Leninist to firm supporter of reform is the focus of Chapter 10. Entitled “Renovation”, the chapter shows this flexible octogenarian earnestly studying the problems of the South and ultimately favouring and proposing reformist solutions. While an older scholarship links the onset of reforms with Truong Chinh’s death and replacement by Nguyen Van Linh at the head of the Party in 1988, Huy Duc credits Truong Chinh’s decisive contribution to the reform. On the other hand, Nguyen Van Linh, depicted in some western accounts as the leader of the reform, comes off in Huy Đức’s story as a vacillating and ultimately conservative figure who squanders opportunities to push the reforms forward after early progress. It is under Nguyen Van Linh that the country’s current orientation—a market economy conjoined to a reactionary and inflexible one-party state—was first consolidated.

Workers say no to Vietnam’s ‘Special Exploitation Zones’

A proposed new law on special economic zones would create enclaves in which key workers' rights and environmental protections are absent, or go unenforced.

Huy Đức’s unparalleled insider knowledge of the country’s elite politics allows him to paint a picture of the adventures of post-war reform that stands out in its level of detail and sophistication over all existing accounts. It is a shame that foreign publishing houses have found the book too long and detailed to commission a translation. I have no doubt, however, that once it comes out in English or French The Winning Side will fundamentally change the way that Vietnam-watchers in the West think about this critical period in the country’s modern history.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss

an

an