A recent visit to Burma brought home to me the fact that, in the minds of many Westerners, the country is still irrevocably attached to the bard of the British Empire, Rudyard Kipling. At the Governor’s Residence in Rangoon, for example, there is a watering hole known as the Kipling Bar, where the hotel’s guests are invited to imbibe, along with their drinks, the atmosphere of the Raj. In its promotional literature, the Strand Hotel proudly (and probably inaccurately) boasts that Kipling once stayed there. A best-selling guide book states that the Pegu Club in Rangoon was where Kipling was inspired to write his famous poem ‘Mandalay’. It was more likely an incident in Moulmein that sparked Kipling’s muse, but this claim is repeated in a brochure produced by an organisation dedicated to preserving Rangoon’s marvellous but now sadly neglected colonial buildings. In other places, and in other ways, Kipling is repeatedly invoked, giving the impression that the poet paid a lengthy visit to Burma and knew it well.

Kipling wrote a number of poems and stories that featured Burma, but he only visited the then province of India for three days, and part of that time was spent at sea. In fact, he later wrote that his sojourn in Rangoon was ‘countable by hours’. Despite the claims of several writers, he never sailed on the Irrawaddy River, nor did he ever visit Mandalay.

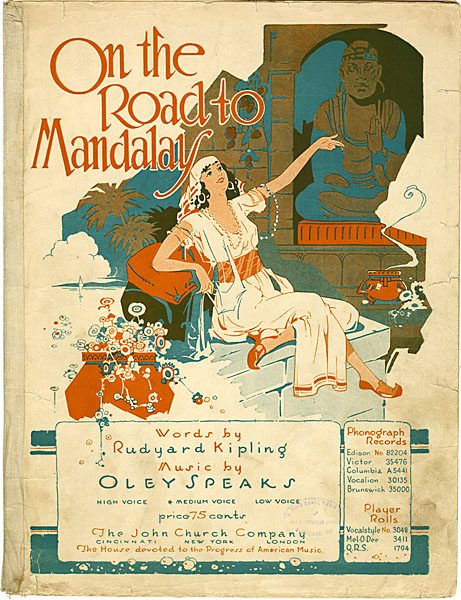

In his essay ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, the poet T.S. Eliot spoke of how, when a new literary work appeared, every existing work was somehow modified by it and the whole scene subtly rearranged. He was speaking purely of literature, and his comment can be applied to Kipling’s oeuvre, but the poem ‘Mandalay’ did this in another sense too. Despite all the critical comments that have appeared over the past 125 years or so, both the poem and its musical settings (usually published under the title ‘On the Road to Mandalay’) have been enormously influential. The poem irrevocably altered public perceptions of Burma, and by extension Western notions of the ‘Far East’. In different ways, and to different degrees, its musical settings coloured almost all the popular songs and tunes about Asia that followed – and there were hundreds of them. As a survey of Burma-related compositions shows, Kipling’s images became fixed firmly in people’s minds and inspired dozens of composers and lyricists in the UK, the US and elsewhere.

It would be going too far to claim that ‘Mandalay’ alone was responsible for the outpouring of songs and tunes during the colonial period that related in some way to Burma. By 1890, when the poem first appeared in print, there was already a long association between the ‘Orient’ and Western music, much of which dwelt on relationships between Asian women and Western men. Also, the poem not only appeared at the height of Britain’s imperial expansion, but it also coincided with a number of social movements in the UK and further afield, to do with questions of race, religion and gender. In addition, soon after ‘Mandalay’ was published, the popular music industry underwent a radical transformation. Technical advances in recording, marketing and broadcasting led to the globalisation of Western music and the appearance of a mass culture that affected most countries, including Burma. Even so, assisted by all those developments, Kipling’s ‘Barrack Room’ ballad had a remarkable impact which is still being felt today.

In literature too, the poem has long been a favourite of publishers and authors. If one dips into the websites of a few prominent on-line booksellers they reveal about 30 works about Burma with their main titles drawn directly from Kipling’s poem. In addition to several named The Road to Mandalay, they encompass such variations as The Road from Mandalay, Back to Mandalay, Red Roads to Mandalay, The Road Past Mandalay and On the Back Road to Mandalay. There are similar titles in French, German and other languages. The publication dates of these works range from the early 20th century right through to the present day. The list includes novels, travelogues, autobiographies, histories, collections of poetry, science fiction stories and books of photographs. Also, ‘Mandalay’ has long been used to punctuate stories about Burma in the news media and to illuminate longer works. This is in addition to a dozen or so feature films, documentaries and travel movies, all named with the obvious intention of capitalising on the popularity of Kipling’s poem, or at least the likelihood that its exotic and historical associations would be recognised and acknowledged.

Once it became well known, the name ‘Mandalay’ acquired commercial value in other spheres. It was applied to condiments and cocktails, ships and streets, buildings and businesses. In 1907, for example, H.J. Heinz invested heavily in his Mandalay Sauce which sought to replicate some of the ‘spicy garlic smells’ described by Kipling. A drink based on rum and fruit juice was dubbed ‘A Night in Old Mandalay’. There was even a children’s board game called ‘Mandalay’, released in 1960. It is stretching a point, but at one stage ‘Manderley’, believed by many to be a variant spelling of ‘Mandalay’, was reputed to be the most popular house name in the UK. In fact, the ubiquity of the name was more likely due to the popularity of Daphne de Maurier’s 1938 novel Rebecca (and Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 film adaption of the same name), in which ‘Manderley’ was the name of the fictional country estate owned by the main character. Even so, the opening line of the novel, ‘Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again’, has been likened by some commentators to the wish expressed by the British solider in Kipling’s iconic poem to return to Mandalay.

During the colonial period, Burma never achieved quite the same status in the mind of the British public as Sax Rohmer’s ‘mysterious orient’, or Walter de la Mare’s ‘heart-beguiling Araby’, but it became an easily recognisable reference point, representing exotic places far away, full of mystery and promise. This was particularly true of Mandalay. Like Timbuktu, Samarkand and other semi-mythical places that captured the popular imagination of the West during the 19th and early 20th centuries, the old royal capital became a powerful symbol. After passing through the city in the 1920s, for example, Somerset Maugham observed:

First of all Mandalay is a name. For there are places whose names from some accident of history or happy association have an independent magic and perhaps the wise man would never visit them, for the expectations they arouse can hardly be realised … Mandalay has its name; the falling cadence of the lovely word has gathered about itself the chiaroscuro of romance.

Maugham felt that the very name Mandalay ‘informs the sensitive fancy’. To his mind, it was not possible for anyone to write it down ‘without a quickening of the pulse and at his heart the pain of unsatisfied desire’. Such was the power of its accumulated associations. The ‘magic’ described by Maugham was in large part derived from Kipling’s ballad, and helped shape the reception given to later musical compositions with Oriental themes.

To use Nicoleta Medrea’s memorable phrase, during the Victorian and Edwardian eras Rudyard Kipling ‘colonised the imagination’ of the West. His ballad ‘Mandalay’ captured ‘the psychic energy of empire’. It became firmly fixed in popular culture and endured into the 21st century. It did not matter if accuracy suffered in the process. By the 1930s, the singer Peter Dawson (famous for his renditions of the song) was claiming that ‘No man knew or saw more, in and about India and Burma, than Rudyard Kipling’. During the Second World War, correspondents in Burma repeatedly invoked ‘Mandalay’ in stories, confident that their readership would make the connection. After a visit to Burma in 1951, Norman Lewis wrote: ‘Mandalay. In the name there was a euphony which beckoned to the imagination’. Hugh Tinker could have expanded the scope of his observation when he stated in 1957, ‘to the average Englishman Burma conjured up one poem and perhaps a short story by Kipling – Kipling, who spent three days in Burma’. Writing in 2002, an American travel writer took a less generous view: ‘Rare is the book about Burma’, he wrote, ‘that doesn’t gush the obligatory line or two of Kipling!’.

This complex amalgam of fact and fantasy, realism and romance, in the public imagination of the West was nicely captured in 2004 by Emma Larkin. In her book Secret Histories, in which she retraced George Orwell’s footsteps in Burma, she confessed to feeling something of the ‘independent magic’ of Mandalay:

I always find it impossible to say the name ‘Mandalay’ out loud without having at least a small flutter of excitement. For many foreigners the name conjures up irresistible images of lost oriental kingdoms and tropical splendour. The unofficial Poet Laureate of British colonialism, Rudyard Kipling, is partly responsible for this, through his well-loved poem ‘Mandalay’.

These sentiments are clearly widely held. As demonstrated by countless modern musicians, authors, film makers, journalists, tour company operators, hoteliers and travel guides, Kipling’s ballad is widely recognised, and still holds enormous appeal. It continues to evoke strong responses among all those who read the ballad or, more likely, hear it sung. As George Orwell once wrote:

Unless one is merely a snob and a liar it is impossible to say that no one who cares for poetry could not get any pleasure out of such lines as: ‘For the wind is in the palm trees, and the temple bells they say, / ‘Come you back, you British soldier, come you back to Mandalay!’.

Andrew Selth is an Adjunct Associate Professor in the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs at the Australian National University. This post draws on Andrew Selth, Kipling, “Mandalay” and Burma in the Popular Imagination, Working Paper No.161, (Hong Kong: South East Asia Research Centre, City University of Hong Kong, January 2015).

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss