A decade has passed since the now-infamous Miss Indonesia pageant winner, Angelina ‘Angie’ Sondakh, entered the People’s Representative Council (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, DPR) on a Democrat Party ticket. The one-time public face of the Democrats’ anti-corruption campaign, Angie is now serving a 12-year prison sentence for her involvement in the Hambalang corruption scandal. Yet she can be regarded as a pioneer among a rapidly expanding class of political actors: the caleg cantik, or ‘pretty candidates’. Caleg cantik are attractive, youthful women, many of whom enter politics having gained notoriety as minor celebrities, socialites, and ‘artists’ (a term which encompasses singers, actors and TV personalities).

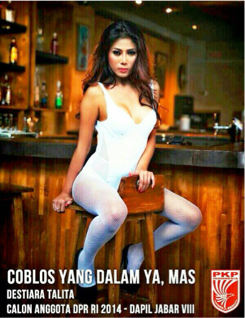

A play on words on this mocked-up Destiara Talita election poster roughly translates as “puncture deep, won’t you, mas [sir]”. In Indonesian elections, voters must puncture ballot papers with nails. (Photo: Twitter)

The 2014 parliamentary elections will see dangdut performer Camellia Panduwinata Lubis (stage name Camel Petir) standing for the Indonesian Justice and Unity Party (PKPI), in a Jakarta electorate in which Indonesia’s overseas diaspora makes up half the constituency. Destiya Purna Panca (better known as Destiara Talita) is also running on a PKPI ticket. A men’s magazine model, Destiara’s inclusion on the Electoral Commission’s fixed candidate roll has not deterred her from uploading saucy ‘selfies’ to her Twitter account. Online satirists have been quick to circulate several of Destiara’s glamour shots, edited to include her party’s logo alongside provocative mock slogans.

Standing in the electorate around Solo is the singer and actress Angel Lelga Anggraeyani, ex-wife of presidential hopeful Rhoma Irama, and the star of several horror films (a genre which, in Indonesia, tends towards equal parts hammed-up ghoul-fest and soft porn). Angel is running for the United Development Party (PPP), and since her nomination has adopted muslimah garb to better fit the party’s Islamic image. Yet shortly after the release of the Electoral Commission’s finalised candidate lists, photos of a scantily-clad Angel went viral on social media, drawing widespread ridicule from the media and blogosphere. This public derision heightened in the wake of an interview on the popular program Mata Najwa, during which Angel demonstrated minimal understanding of her party’s platform, failed to articulate any distinct policy positions, and acknowledged that she had only entered politics after encountering the Religious Affairs Minister and PPP chairman Suryadharma Ali at a party.

Akbar Tandjung, the former Speaker of the DPR and a senior Golkar Party statesman, has singled out Angel’s candidacy for criticism, while arguing that the proliferation of celebrity candidates standing in 2014 reflects the failure of parties to develop effective cadreisation programs. Unable to source high-quality candidates internally, parties have often turned to individuals with pre-existing public profiles. Not only do celebrity nominees benefit from high levels of name recognition, but they are equipped with the resources to finance their campaigns, making them doubly attractive to cash-strapped parties.

Given that statutory regulations require parties to nominate women for one third of their legislative candidacies, and to ensure that women comprise 30% of their internal functionaries, it is perhaps unsurprising that those with small cadre pools (such as Hanura, Nasdem and PKPI) have looked to female celebrities to meet their gender quotas. Yet in 2014, the caleg cantik phenomenon is no longer so closely tied to celebrity: a thread from the Indonesian discussion forum kaskus.co.id, published in January 2014, lists more than one hundred caleg cantik, including some standing for subnational legislatures rather than the national parliament. Celebrities, women involved in the fashion and beauty industries, and ‘society ladies’ enjoy disproportionate representation among this group, while a number of the candidates have familial ties to well-known political figures, and can therefore be counted among Indonesia’s politico-social elite. Yet it is important to note that the list includes candidates with less glamorous backgrounds: a student, a doctor and a kindergarten teacher all make the cut. Relatively few are identified as party members or activists. What these women share is the ‘caleg cantik’ tag, and the often negative connotations associated with this phenomenon.

The comments of kaskus users, by and large, do not discriminate between celebrity and non-celebrity caleg cantik. Thanks to their public notoriety, the Angels, Camels and Destiaras are considered representative of many young female candidates. The response from bloggers is by and large negative, characterising these women as low-quality nominees who have profited from sex appeal at the expense of more “worthy” parliamentary aspirants. Young female candidates identified as caleg cantik, regardless of their personal qualities, can be hastily painted as the beneficiaries of a political culture plagued by superficiality, nepotism and sexual misdemeanour.

“Do we want parliament to become a giant salon?” asks one kaskus user. “Pretty faces don’t guarantee good behaviour and performance, especially when most [of these candidates] are artists, models, singers, entrepreneurs, [or] the children of officials. Most of [them]… possess little political understanding or concern for ordinary people. Girls from the socialite class are usually prone to hedonism, materialism, [and] indulgence.”

An article published on the opinion blog kompasiana in February 2014 suggests that many party leaders have sought to attract apathetic voters by associating their party brands – and themselves – with beautiful young women ahead of this year’s election.

The foregrounding of pretty faces in narcissistic poses is an attempt at political communication in a climate of public apathy. [The effect] of this approach is to sideline political competency. As long as [a female candidate] has a photogenic face and can make a certain contribution to a party[’s vote], she is guaranteed a place on a legislative ticket. This is no longer a secret.

This view cannot be dismissed, given a campaign environment where individual candidate recognition is low, but visual advertising (in the form of posters and billboards, or baliho) tends to saturate electorates.

It remains to be seen how this apparently heightened emphasis on the aesthetic merits of female candidates will affect Indonesia’s drive for gender equality in the political sphere. Given that many of these caleg cantik are standing for smaller parties, there is relatively little chance of election for many of them. Whether by (mostly male) party administrators during the nomination process, or the popular commentariat following their nomination, it appears that even non-celebrity female candidates are being judged according to criteria rarely applied to their male counterparts. It is certainly concerning if parties are indeed ‘playing’ gender quotas by prioritising aesthetics over aptitude, but it is equally worrying if voters, perceiving such a trend, are dismissing young, female candidates on the basis of sexist stereotypes. The achievements of artists-turned-parliamentarians such as the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle’s Rieke Diah Pitaloka and Golkar’s Nurul Arifin are testament to the fact that any supposed dichotomy between ‘caleg cantik’ and capable candidates can be a grossly misleading one.

………

Thomas Power is a PhD candidate at the Department of Political and Social Change at the Australian National University. He is researching patterns of candidate recruitment and party institutionalisation in Indonesia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss