Substantial legal reforms and a coordinated push to educate on tolerance, diversity and gender equality are the only way to stop endemic sexual violence in Indonesia, Saskia Wieringa writes.

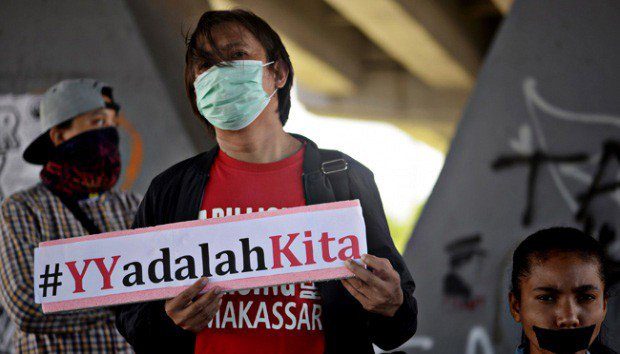

The gang rape and gruesome murder of Yuyun, a 14-year-old schoolgirl in Bengkulu, Sumatera made international headlines. However, the story only came to the world’s attention after feminist activists started a social media campaign, a month after the girl’s body was found.

Sexual violence is rife in Indonesia. In another recent case a girl was gang raped in Manado, two of whom were identified as police officers. There are stories of rape or sexual violence on an almost daily basis, with many assaults resulting in the murder of the victim.

The ones that make headlines are only the tip of the iceberg. In Indonesia caste or inter religious factors do not immediately account for present day outbursts of sexual violence. Racial, ethnic and class factors, however, do play an important role.

The National Commission on Violence Against Women estimates 35 women per day are victims of sexual violence and that, as everywhere else in the world, violence against women is under-reported. Similarly the Women’s Association for Justice, with 18 offices all around the country, deals with many cases of domestic and other forms of violence against women. The Commission was set up by former President Habibie following the overthrow of the ruthless military regime of President Suharto after the brutal rape and murder of scores of Chinese girls and women during the so called ‘May riots’ of 1998.

The fact-finding team established by the Government to investigate these events verified 66 rapes of women, the majority of whom were Sino-Indonesian, as well as numerous other acts of violence against women. They also found that sexual violence had occurred before and after the May riots. The so-called ‘New Order’ of President Suharto rested on a masculinist military culture in which women’s rights were trampled on. The regime was built on the massacre of hundreds of thousands of leftist people and spurred on by the sexual slander against communist women. In the process the military raped, sexually tortured and murdered tens of thousands of women and girls.

It began when a group of middle-ranking army officers abducted the top brass of the Indonesian army. The bodies of the abducted military personnel were dumped in a disused well on a training field of the air force, called Lubang Buaya, Crocodile Hole. To this day mystery surrounds these events. What is clear is that in the end Suharto managed to oust President Sukarno, in March 1966, and the Communist Party was blamed for the murders.

From early October onwards, the army waged a relentless campaign to blame the Communist Party. In particular, they did so by building a campaign of sexual terror around the young girls who had been present at the Crocodile Hole. They were accused of having seduced the generals in a lurid dance (Fragrant Flowers Dance) and of having castrated and murdered them.

The “proof” for these stories came from “confessions” signed after heavy sexual and other physical torture and the taking of nude photographs of the girls in prison.

Indonesia’s National Human Rights Commission released a report in 2012declaring the military responsible in gross human rights violation in 1965. The prosecutor’s office rejected the report.

Under Suharto, women’s subordination became enshrined in the legal and social structure of the country. In the 1974 marriage law for instance, women are defined as housewives, who have to sexually satisfy the needs of their husbands, who are the heads of household. If they don’t, their husband is entitled to marry one or more extra wives. The word for a heterosexual woman having sex with her partner is ‘serving’ that partner. Thus women are objectified in this and other laws. Lower class women and those belonging to ethnic and religious minorities are especially vulnerable within this highly unequal gender regime.

The Ministry intended to fight for women’s rights, presently entitled the Ministry for Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection, does neither. Far from empowering and protecting women and girl children, it actually disempowers them. It promotes the concept of ‘gender harmony’, which enshrines women’s subordination. The role of women is defined as the less important instruments in the orchestra which has to produce this harmony. Another concept it advocates is the Arabic for ‘happy’ in the construct of ‘happy family’. This kind of family is composed of pious, obedient women and strong fathers.

Women’s subjugation is also advocated by the many neo-salafist (also known as wahabi Islam) preachers, schools and institutions which have blossomed since the fall of Suharto. Masculine superiority and feminine subservience are not seen as the products of historical, cultural and religious factors but are naturalised. Extreme cases of violence such as gang rapes and murder are often portrayed as arising from external factors and thus “otherised”. The culprits may be foreigners, such as the high profile case of the Canadian teacher Neil Bartleman, who was convicted of paedophilic sodomy on extremely flimsy grounds, or on LGBT people who are routinely associated with paedophilia, even by political and intellectual leaders who have been trained to know better.

Alternatively, the violence is blamed on moral factors, which are the target of a particular fundamentalist-inspired campaign, such as that against alcohol. The boys who gang raped Yuyun in Bengkulu were portrayed as being drunk on home-distilled arak.

What is not acknowledged as the cause for this violence against women is the country’s history, culture and social norms.

So what is the answer?

A strengthening of religious teaching in the school curriculum, a new institution for child protection, the passing of the proposed Elimination of Sexual Violence Law or hefty sentences for culprits are measures being discussed at present. This form of education should be based on religious tolerance and on the many recommendations the National Commission on Violence Against Women has made. Such changes will not immediately lead to the dismantling of the culture of violence, nor to the growth of a culture of respect for human and women’s rights. For that Indonesia has to face its violent past and educate its enormous population on tolerance, diversity and gender equality.

Saskia Wieringa is Professor and Chair of Gender and Women’s Same-Sex Relations Crossculturally, University of Amsterdam.

This article is a collaboration between New Mandala and Policy Forum, the Asia and the Pacific’s leading platform for policy insight and debate.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss