Malaysia needs serious electoral reform to prosper, writes Teck Chi Wong.

Malaysia’s enthusiasm for electoral reform is arguably at its lowest point, after being high on the tide in the past 10 years as reflected by successive Bersih gatherings from 2007 to 2016.

But electoral reform is now more important than ever, particularly after the 1MDB scandal. If the authoritarian and corrupt political system is not overhauled, it will seriously impede the country’s ability to achieve high-income status in the long run.

In Malaysia, growth is never purely about the market. The state has been, and still is, playing important roles in steering and managing the economy. In fact, Malaysia was regarded in the 1990s as one of the successful models of the ‘development state’ in East Asia, which through learning and transferring resources to productive sectors had successfully industrialised the country and lifted many of its citizens out of poverty.

These East Asian developmental states, including Japan, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea, shared some common characteristics. Many of them (except Japan) were authoritarian regimes in the 1970s and 1980s. But all of them were strong in facilitating policies and learning from others for growth.

On top of that, being authoritarian also helped these countries to stabilise their political landscape and therefore create a business environment which encouraged foreign investment to flow in. However, in Malaysia, it came at a tremendous and bloody price: the racial riots of 1969.

Key to this development model is the quality of the state. But it is difficult for these authoritarian regimes to maintain or improve their quality in the long run. Authoritarian order means that a lack of appropriate checks and balances for those in power leaves the system susceptible to corruption. At the same time, social and economic development gives rise to new needs and demands of accountability and integrity from the publics. As a result, political and social tensions emerge.

The East Asian developmental states approached this problem differently. Both South Korea and Taiwan had since democratised in 1980s and 1990s. Intense political competitions subjected those in power to greater checks and balances, and therefore reduced the most blatant forms of corruption.

Singapore, meanwhile, is an outlier. Despite not much progress in terms of democratisation, the city state has been outstanding in eliminating corruption. Many would point to the tough law and the high salaries of politicians and civil servants for the reason behind low corruption in the country. But exactly how Singaporean leaders could be disciplined despite no strong institutional checks and balances is still subject to debate, although this could possibly relate to their strong desire to guarantee Singapore’s survival in the international market and the region.

Malaysia is stuck in the middle. Not only is it in the middle-income trap, but it is also wrestling between authoritarianism and democracy. The quality of its institutions, including its cabinet system, parliament and judiciary, has been on the decline and they cannot mount any effective checks and balances against UMNO, the dominant ruling party. Resultantly, corruption and patronage are widespread in the government.

This has serious implications for the economy, particularly when the country is seeking to leave the middle-income trap. To entrepreneurs, rent-seeking is simply more profitable, as reflected by the fact that most of the wealth of Malaysian billionaires is created in rent-heavy industries, like banking, construction, housing development and resources.

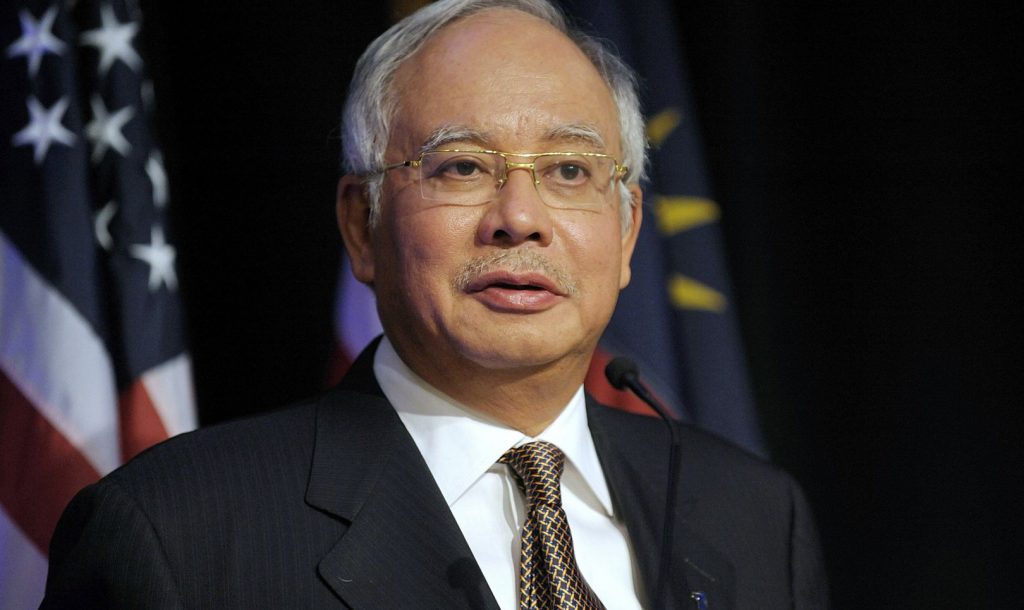

All of these forces are embodied in the recent 1MDB scandal. Although Prime Minister Najib Razak is accused of embezzling billions of public funds and the scandal has rocked investor confidence, no institutions could effectively hold him accountable and no amount of public pressure could force him to step down. As long as Najib is controlling UMNO, his position is solid, as opponents are eliminated from the government and the party.

If there is one lesson we can learn from South Korea and Taiwan, that would be democratisation can help to change the underlying political structure and strengthen the quality of the state. Through intensified political competition and appropriate checks and balances, the public can put more pressure on those in power to be more accountable and focus on economic development.

In fact, the difference between South Korea and Malaysia is particularly stark now that Park Guen-hye, the former President of South Korea, was impeached and jailed. This happened just within months after the corruption scandal involving Park’s best friend erupted in October last year.

In Malaysia, the overhaul in political structure over the long run must be achieved through electoral reform, which includes making the Election Commission independent and reducing gerrymandering and malapportionment. As long as the electoral system is not changed, UMNO can remain in power by holding onto its support bases in rural areas. The recent controversies surrounding redelineation process just again highlight the need for reform.

To many, for Malaysia to regain its shine after the 1MDB scandal, Najib must go. But, that would be just a tiny first step on a long journey to reform and democratise its political institutions.

Teck Chi Wong is a former journalist and editor with Malaysiakini. He is currently pursuing a Master of Public Policy at the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss