About a year ago, a friend in my neighbourhood put stickers on his van that said: “I will not be the cause of racial or religious conflict.” A little later, he peeled them off. “I was worried people would be angry or violent towards me when they saw the sticker,” he said. “The van is for business.”[1] Who would I be to disagree? The stickers were from a campaign organized by youth groups opposing the spread of religious violence following the riots in Meiktila. My friend supports his family by driving that van.

The other day, I bumped into another friend. I hadn’t seen her in a while but on Facebook I’d been seeing regular photos of her at public speaking events. She is young and articulate and Muslim. Great job, I said. “I’m worried about my security,” she said. “I’m worried that other Myanmar people may misunderstand me. I’m not worried about the government. They already put me in jail one time, what more can they do?” There are others that are more frightening.

Aung San Suu Kyi has drawn criticism and ire from erstwhile international supporters for failing to speak out, properly. Last year, western media outlets lampooned her[2] when she told the BBC, violence has occurred on both sides.[3] She’s no champion of human rights, they said. A politician that knows which way the wind blows, they said. Both sides feel fear, she said.

She is right, though. Each side feels fear. The language of existential threats to nation and religion that I started noticing in neighbourhood conversations a year ago are still there[4], and not just in west Yangon.[5] It’s hard to talk about religion without this spectre in the background. A prominent religious leader may say, simply, “My religion is peaceful,” and the audience may understand this as a generalized call for peace. Or they may understand it as proof of superiority and a call to arms, against non-peaceful religions next door.[6]

When a nation faces an existential threat, everyone is duty bound to raise the alarm. “Let’s kill with words to reduce the actual killing,” a prominent politician recently posted on Facebook. The most alarming such words have attracted international attention and condemnation. Facebook groups called the “Kalar Beheading Gang;”[7] a leading monk on the cover of TIME Magazine as the “Face of Buddhist Terror;”[8] government officials calling Muslim groups “Ogres”[9] and “dogs.”[10]

Dehumanization of an entire population should be grave cause for concern.[11] It is much less difficult to kill an animal than a person; such discourse has aided every instance of genocide and mass atrocity in modern history.[12] It takes a whole host of factors for mass violence to be possible.[13] But no matter all else, violence must be justified. Those who give orders to kill, those who kill, and those who otherwise participate or stand aside must be motivated to do so.[14] Violence, especially on a mass organized scale does not “erupt” or “explode.” It is mobilized, organized, rationalised.

There is plenty else being said in Myanmar today that sounds less extreme yet is nonetheless promoting hate, stoking fear, enabling violence. On Facebook, I see a regular stream of terrible news from Muslim countries, discussed in Burmese. Brunei is introducing Sharia law. Look at the awful crimes committed by Boko Haram. This is just news, not hate speech – but news that contributes to the construction of Islam-as-threat, of Buddhist Myanmar facing existential risk. Afghanistan and Malaysia used to be Buddhist countries, too. Myanmar, watch out! Few things are more powerful than a little bit of truth, selectively shared.

Aung San Suu Kyi is right, both sides feel fear. In a climate of fear, how does it become okay to say, I don’t support violence? To say: I do not appreciate virulence, hateful speech, rumours and fear mongering that spark violence.

Last week, more than 100 civil society organizations released a statement “strongly rejecting” a new law regulating inter-faith marriage that is being pushed by the associations to protect race and religion. “We believe that current faith-based political activities, including the arguments against interfaith marriage currently taking place in the country, are not in accordance with the objectives of the peaceful coexistence of all faiths and the prevention of extreme violence and conflict,” the statement said.[15]

The response was swift and strong. “Traitors,” English-language media quoted U Wirathu at a public talk organized by the Patriotic Youth Network inside a sports stadium in north Yangon.[16] He did call them traitors, but “traitor” does not encompass everything he said. I’m still struggling with the interpretation. It was: “fake countrymen.” It was: “Impure people.” It was: “When you [impure countrymen] hear the applause at this event, you will feel distressed.” “We record your names as traitors,” echoed the association to protect race and religion in Shan State, in a statement that listed by name eight of the individual civil society leaders who have publicly opposed the proposed law. A prominent politician responded on his Facebook wall: “Dear Muslim groups, we don’t wish to fight with you. You can convert these [groups that oppose the proposed law] and rape them if you want to.”

At the end of March, I watched ex-political prisoners and other activists milling around in a hot meeting room, waiting for a press conference to start. When it started, it was jarring and forceful and shook everyone to attention; one of the activists, standing in front of the microphones, beating a computer keyboard onto a desk covered in flowers. Spitting on to the shattered plastic and petals, he offered them to the audience, unwanted.

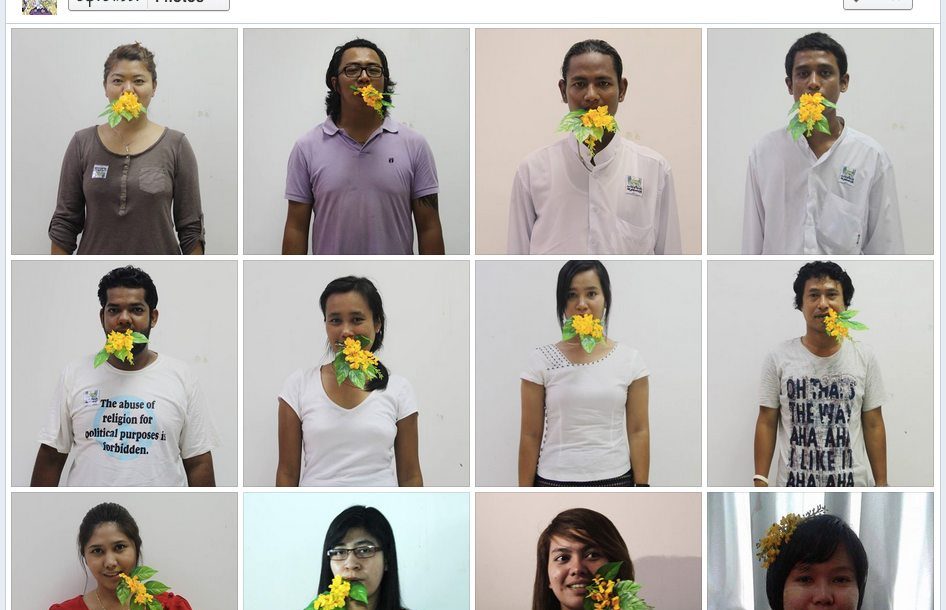

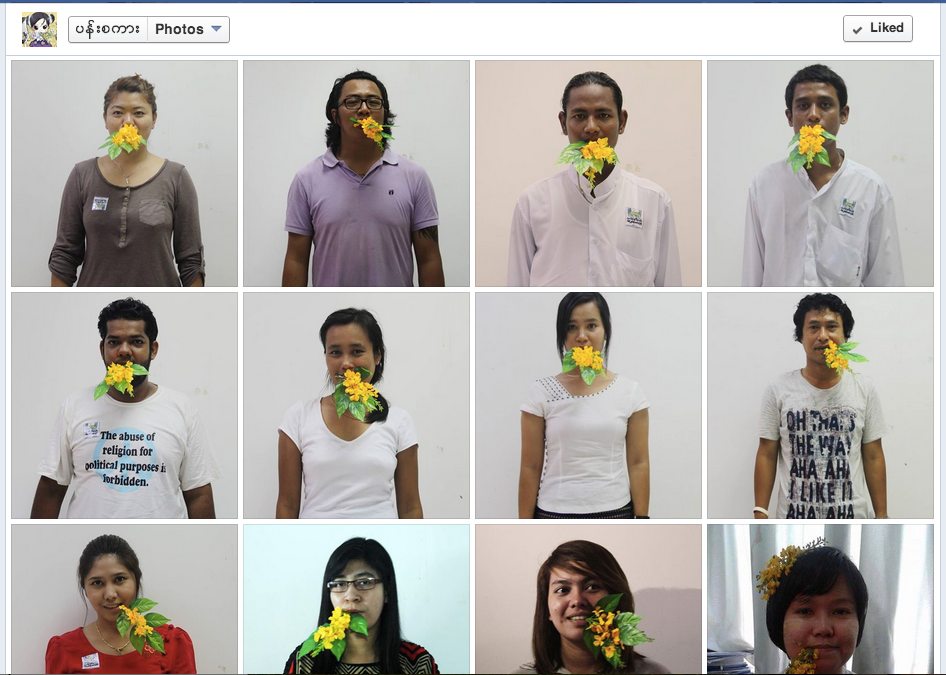

Flowers, cherished or defiled, can be infused with many meanings. Beauty and love; peace, as stopper in the barrel of a rifle.[17] At the press conference, the activists said: “Don’t spark hatred with your words.” “Be responsible in what you say,” they said. After they spoke, those in the room began posing for photographs, with yellow padauk flowers in their mouths. In Myanmar, yellow padauk flowers mean it is the Thingyan New Year. Some people will also say that padauk pan are the national flower, that they represent strength, honesty. If flowers can have many meanings, words can call those meanings forth. “Words can destroy the whole country,” the activists said. With padauk flowers in their mouths, they said: “Speak pan zagar [‘flower speech’], instead.”

Over the next few days my newsfeed began to be taken over by similar photographs, of friends with flowers in their mouths, out on Yangon’s hot streets distributing stickers, posters, t-shirts, wristbands; singing songs, speaking out against speech that causes hate, calling for a pan zagar movement. A Pan Zagar Facebook page gained followers by the thousand, daily. When the Thingyan holiday arrived I escaped for a quiet paper-writing refuge with family, but each day, each time a group in a new city joined the movement, their photos appeared as a reminder in my newsfeed: “Speak pan zagar.” A reminder: you are not alone in your opposition to sparking hatred.

I am back in Yangon now. In the last few days, I saw on Facebook that young people in three more cities have been on the streets with stickers and flowers. Six weeks after jolting a room to attention with a shattered keyboard, youth in at least 27 cities have taken part. Prominent artists, ex-political prisoners, prominent religious leaders, have voiced their support. More than 11,000 people support Pan Zagar on Facebook.

The politician that wants to kill with words responded: Muslims are attacking us, and Burmans talk about hate speech? Soon after, he posted a photo of a grave marked with the name of a woman, “Ma Thida Htwe.” Her rape and murder, which Myanmar language media noted was committed by “Bengali Muslims,” is widely recognized to have motivated the retaliatory massacre of a bus full of Muslim pilgrims in Rakhine State in June 2012. The politician’s post was a reminder that May 28 will mark the two-year anniversary of her violent death, and a call for people to change their profile photos to her gravestone on May 27 and 28.

A few weeks ago, another friend from the neighbourhood was in my apartment, helping make a spare water tank out of a barrel once used to transport shampoo. He is a plumber and an electrician. Like his brother, he is a champion chinlone player and, lately, I think the only time he takes off the Bluetooth earpiece for his new mobile phone is when he is on the dusty court in front of our quarter’s pagoda complex. He picked up a pan zagar sticker from my kitchen table, the last of the handful I’d taken from that first press conference. “My friends have been giving those out,” I said. He nodded as he peeled the backing off the sticker. Then he put it on his mobile phone and we went back to work.

Let’s kill with words, says the politician on Facebook, and turn photos to gravestones. I wonder, how long will the pan zagar sticker stay on my friend’s phone?

[1] Matt Schissler, ‘Conversations After Lashio’ (New Mandala, 3 June 2013) <asiapacific.anu.edu.au/newmandala/2013/06/03/conversations-after-lashio/> accessed 11 March 2014

[2] David Blair, ‘How Can Aung San Suu Kyi – a Nobel Peace Prize Winner – Fail to Condemn anti-Muslim Violence?’ (News – Telegraph Blogs, 24 October 2013) <http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/news/davidblair/100242929/how-can-aung-san-suu-kyi-a-nobel-peace-prize-winner-fail-to-condemn-anti-muslim-violence/> accessed 10 May 2014

[3] ‘Suu Kyi: Burma’s “Climate of Fear”’ (BBC News, no date) <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-24651359> accessed 10 May 2014

[4] Schissler, ‘Conversations after Lashio’ (n 1)

[5] Nyi Nyi Kyaw, ‘Securitization and Islamophobia Analysis of the 969 Movement in Myanmar’ (Islam, Law and the State in Myanmar, Centre for Asian Legal Studies, National University Singapore, 23 January 2014); Kyaw San Wai, ‘Myanmar’s Religious Violence: A Buddhist ‘Siege Mentality” at Work’ (2014) No. 037/2014 S Rajaratnam Sch Int Stud Comment

[6] Matt Schissler, ‘Sleeping Dogs’ (New Mandala, 20 January 2014) <asiapacific.anu.edu.au/newmandala/2014/01/20/sleeping-dogs/> accessed 11 March 2014

[7] ‘Internet Users Unload Anger on Social Media Sites’ [2012] AFP

[8] Hannah Beech, ‘The Face of Buddhist Terror’ [no date] Time

[9] ‘“Ugly As Ogres:” Burmese Envoy Insults Refugees’ [2009] Huffington Post

[10] Robin McDowell, ‘The Suffering of “Dogs”: Rohingya Kids in Western Burma’ [2013] AP

[11] Nice, Sir Geoffrey and Francis Wade, ‘Preventing the Next Genocide’ [2014] Foreign Policy

[12] David Livingstone Smith, Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others (New York, St Martin’s Press 2011)

[13] See for example Charles Tilly, The Politics of Collective Violence (CambridgeтАп; New York, Cambridge University Press 2003).

[14] Jonathan Leader Maynard, ‘Rethinking the Role of Ideology in Mass Atrocities’ (2014) 26 Terror Polit Violence 1

[15] ‘Statement of Women’s Groups and CSOs on Preparation of Draft Interfaith Marriage Law’ (Public Statement 6 May 2014); ‘Women of Burma Speak Out Against Interfaith Marriage Act | DVB Multimedia Group’ (no date) <https://www.dvb.no/news/women-of-burma-speak-out-against-interfaith-marriage-act-burma-myanmar/40401> accessed 13 May 2014

[16] ‘Nationalist Burma Monks Call NGOs “Traitors” for Opposing Interfaith Marriage’ (no date) <http://www.irrawaddy.org/burma/nationalist-monks-call-ngos-traitors-opposing-interfaith-marriage.html?PageSpeed=noscript> accessed 13 May 2014

[17] As in the iconic photo of anti-war protestors placing flowers in rifle barrels of American soldiers in 1967. See, Adam Bernstein, ‘Bernie Boston, 74; Took Iconic 1967 Photograph’, The Washington Post (24 January 2008) <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/01/23/AR2008012303713.html> accessed 11 May 2014

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss