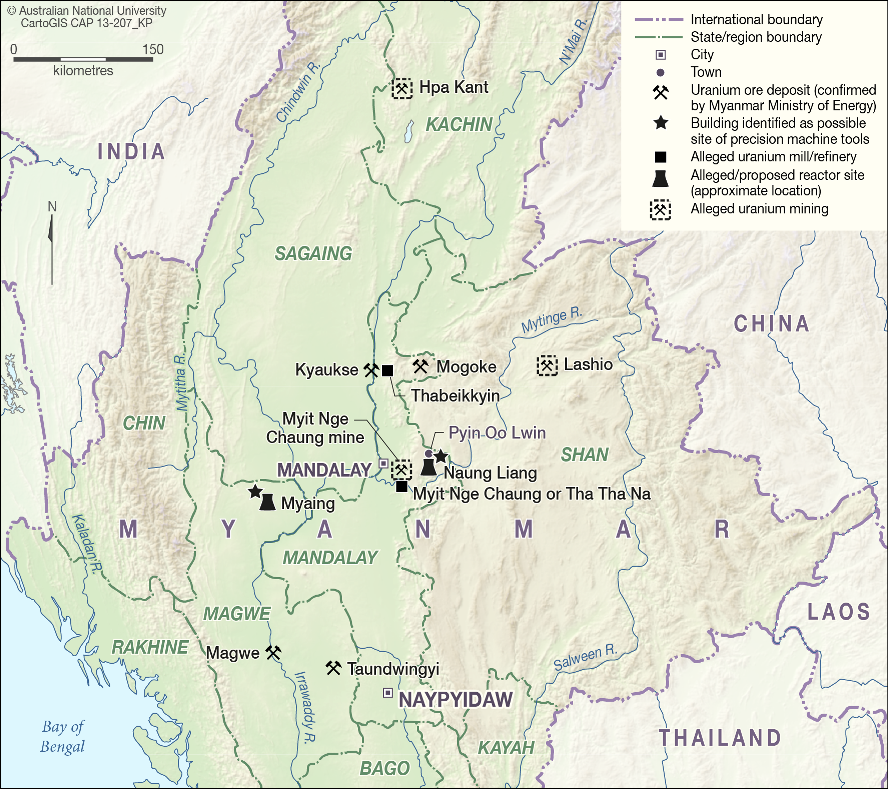

Map: Possible nuclear-related sites based on report by Desmond Ball, Robert Kelley, Bertil Lintner, Andrew Selth and the Institute for Science and International Security.

Since Myanmar’s 2010 general election, the Thein Sein government has been preoccupied with significant economic and political reforms. Its policies can be considered as part of an overarching strategy for stability, unity and peaceful development.

Naypyidaw’s international relations agenda has been influenced by years of sanctions from the West. Myanmar’s policies are now part of a complex web of maneuvers to consolidate regime and state security through close economic and political relationships, especially within Southeast Asia. Rightly or wrongly, the international community tends to be much more concerned about weapons of mass destruction (WMD) issues than other humanitarian and internal human rights issues. North Korea and, more recently, Syria provide excellent examples of this phenomenon.

Compared with Myanmar’s ongoing ethnic conflicts and corruption, progress on the nuclear issue is relatively achievable and it could be a good starting point for improving diplomatic relations with the rest of the world.

Nuclear activities and accusations

Myanmar concluded a nuclear safeguards agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the United Nations’ ‘nuclear watchdog’, in 1995. However, Myanmar consistently maintained that it did not have any nuclear activities so the Agency had nothing to inspect.

In late 2010, it was reported that Myanmar simply chose not to respond to a request from the IAEA for a visit. Since then, it has started to act more receptively towards the Agency.

At the September 2011 General Conference of the IAEA, the leader of the Myanmar delegation declared: ‘Myanmar is in no position to consider the production and use of nuclear weapons and does not have enough economic strength to do so…Myanmar has halted its previous arrangement of nuclear research as international community may misunderstand Myanmar over the issue.’

Myanmar has some of the basic elements of a nuclear weapons program but, regardless of its past intentions, it is a long ways from a nuclear weapon capability. Myanmar has some expensive, precision machine tools (which could be used in both nuclear and other high-tech industries), probably opportunistically procured from Europe, China and Singapore.

Hundreds of the nation’s engineers received training in Russia. In 2007, Myanmar signed an agreement with Russia for the sale of a reactor. The reactor may have been destined for a site identified by defectors near Magwe but everything was shelved in 2011. There are also a few suspected uranium mines and mills in the country. In principle, Myanmar could argue that these activities do not constitute violations of its existing safeguards obligations.

Myanmar may also have used equipment to conduct conversion on natural uranium. This would be a safeguards violation but, if confirmed by inspectors or admitted by the government, it is unlikely to attract much condemnation. Based on the scale of its equipment procurement, it is doubtful that Myanmar could convert enough uranium to produce reactor fuel or undertake significant enrichment activities.

The most serious of the detailed accusations made by defectors is that Myanmar is working with North Korea (or was a few years ago) to construct an underground reactor near Naung Laing and that, at least for a time, a plutonium reprocessing plant was planned for the same site.

Role of inspections

Myanmar signed an ‘additional protocol’ to its safeguards agreement at the IAEA General Conference in September 2013. Once Myanmar implements this protocol, it will improve the Agency’s access rights in the country.

Given that Myanmar is unlikely to be anywhere near having a nuclear capability, it might actually be fairly forthcoming about its past. There is little to be gained by remaining opaque if it invites the rest of the world to assume the worst about Myanmar and its relationship with nuclear-armed North Korea. Analysts have identified a number of locations where the machining tools and other rudimentary equipment may be stored, on the basis of satellite imagery and the testimony of defectors. As expected, these locations tend to be in areas that the government effectively controls. This is important because the government would likely oppose IAEA inspector access to war-torn parts of the country, viewing this as undue international interference by a UN affiliate.

It would be useful to check some locations, particularly alleged sites of uranium mills/refineries, to determine whether Myanmar was successful with converting uranium, and also to prove that it has not engaged in enrichment or reprocessing. In August this year, the IAEA conducted a workshop in Naypyidaw at Myanmar’s request to assist the country with establishing the necessary administrative arrangements to make reports under the additional protocol. A logical next step would be for the IAEA and Myanmar together to choose one of the possible nuclear-related sites for a practice run of the so-called ‘complementary access’ techniques permitted under the additional protocol.

Even after the additional protocol enters into force, the Agency will make only limited use of its complementary access power to raise questions about perhaps a couple of the alleged sites per year. The Agency can then visit these sites, but access will centre on verifying the absence of non-naturally occurring nuclear materials, such as converted and enriched uranium or plutonium. This is usually accomplished by taking ‘environmental samples’, which are essentially just swabs that can then be laboratory tested to check for tiny traces of these materials.

Inspectors may be able to verify the absence of nuclear fuel at the alleged underground reactor site by negotiating access near the entrance. Myanmar may refuse to let inspectors inside the complex by claiming that the site is a sensitive conventional military installation.

Determining the fate of the machine tools or the existence of a possible half-built underground reactor will depend on the quality of Myanmar’s cooperation. These issues could most likely be deferred for the time being.

Chemical weapons?

Myanmar is also one of the original signatories to the Chemical Weapons Convention but has not ratified it. The Chemical Weapons Convention, and inspections by its Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, may present some additional difficulties for Myanmar.

There are scattered reports of Myanmar using chemical weapons in ethnic conflicts and defectors have made claims about their deployment, primarily in southern and eastern parts of Kachin State. If Myanmar has a chemical arsenal, it is probably much smaller and less sophisticated than, for example, Syria held. However, components might be dispersed around the country, making verified destruction a slow process.

The Chemical Weapons Convention also requires on-going routine inspections of a variety of peaceful chemical industries. Given the state of Myanmar’s economy and development, it probably does not have many facilities in this category. Assuming progress in foreign investment is sustained, Myanmar might eventually establish significant chemical manufacturing industries (eg, pharmaceuticals, plastics and pesticides), at which point it should come under international pressure to ratify the convention.

Agriculture, medicine and industry in Myanmar also stand to benefit from its increasing involvement in technical cooperation with East Asian states in nuclear science and applications. Myanmar has a vested interest in being seen to be a responsible actor in these areas.

The WMD dimension is likely to be only a very small part of the security issues to be overcome as the nation progresses toward better relations with the international community but it is a good place to start.

Given the many other challenges facing the government, it could be a couple years before Myanmar puts in place the modest administrative arrangements necessary to ensure that it can meet its reporting and inspection obligations under strengthened safeguards. In the meantime, Myanmar can build international confidence in its stated commitment to non-proliferation by cooperating with the IAEA in investigating its past and allowing provisional access for inspectors to a few agreed sites.

Kalman A. Robertson and Olivia Cable are graduate students in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss