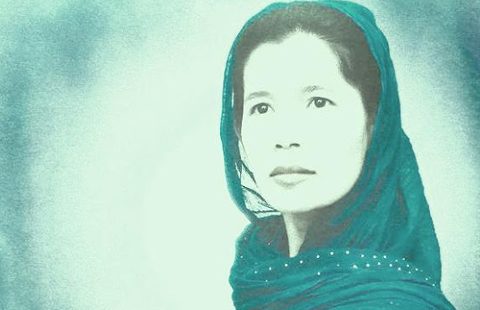

Last month (August 15) saw the 10-year anniversary of the signing of the Aceh peace accord. To mark the occasion, Kathryn Robinson reviews a new volume by local poet Zubaidah Johar, Building a boat in paradise, which powerfully recounts the experiences of women in Aceh’s troubled past and uncertain future.

Zubaidah Johar’s latest volume of poetry is moving and powerful.

The poems give literary expression to her tireless commitment to transformative change in Aceh, in which she has been actively involved

Indonesia has a remarkable tradition of political poetry which has been used to challenge unjust and self-serving governments. This includes figures such as WS Rendra and Putu Oka. Many of these authors were jailed by previous regimes, in order to silence their critical voices. Zubaidah uses her poetry to provide a historical record, and a strong plea for justice and recognition, from the over 300 women whose stories she heard.

Harry Aveling has commented on the flowering of Indonesian critical writing since Reformasi and he especially comments on the work of women writers, and Zubaidah’s work fits squarely in this camp. Taking his lead from a poem by Dorothea Rosa Herliany, entitled ‘Ziarah Batu‘ he says that these writer ‘all use “the language of rocks” as a way of attacking the hypocritical “arrogance” of the society they live in and assert the rights of the tongues of women to speak in an honest, frank and unrestrained manner ‘ [i]

Her powerful poems, critique cruel oppressors, and capture the distinctive voices of women who have been tortured, vilified but not crushed.

Anthropologist Michael Taussig[ii] asks ‘How do we explain how fear gets a grip on the human heart’? In his view, social science approaches are inadequate to provide an understanding of terror –its operation and effects.

Zubaidah’s poems take us into the domain of fear: but entering into Acehnese women’s horror we do not feel their abjection. Rather, we feel their anger, resistance and personal solidity in the face of military action designed to bring shame and hence a dissolution of self. Perhaps surprisingly, we feel their determination and awesome will to endure, to keep going, and to ensure the survival of their children, their families and their land. The poems communicate a terrifying sense of the way the military manipulated potent cultural symbols in their reign of terror. The rumah geudong, the Acehnese women’s space and the heart of women’s domestic power is desecrated with the blood of raped and tortured women.

But the poems powerfully reinscribe these symbols–the blood shed by the women symbolises sacrifice and hence power, not the victimhood intended by the perpetrators. The heroic struggles and the sacrifice of women- expressed in terms of their corporeality- their rent wombs, spilt blood and trampled breasts. The spilt blood also invokes the ‘tanah tumpah darah’ so strong in Indonesian nationalist symbolism

For me, the poems also invoke the figure of the ‘Demon Lover’ so-named by feminist author Robyn Morgan in her invocation of the ‘collateral damage’ to humanity caused by the Palestinian crisis[iii]. The brutish daily struggle of armed resistance carried out by men transforms them into ‘demon lovers’ who become cruel and indifferent to their own womenfolk.

But

Once he found out

My blood had been spilt in the rumoh geudong

He left without a sigh

Leaving his seed in my womb

(Memories of Rumoh Geudong II)

There is a bitter weighing up of men and women and the men are found wanting. The women are represented a resolutely loyal to the absent fighters and to their family ties.

Yes off we went like the wind

But our blood was still boiling in rage

What else could we do?

If we say too much our men will never come back

If we change our story there will be bloodshed

If we say nothing

they will still hunt down our men

Better to flee in silence

while taking the next steps to survive

(Is this your peace sir?)

The poems in the last pages of the collection turn to the post-conflict period after the tsunami and the new threat of social and cultural dissolution from the actions of the ‘troops’ of the aid and development agencies. Here, the risk is greed that threatens to dissolve the social bonds that have survived first the years of conflict and then the tsunami. In a poem that has the feeling of Haiku, but also a pantun she asks:

Now what is happening on the verandah!

The people are counting their profits

Snatching a bucket to catch the rain

(December Notes)

The poem ‘Peace for Whom?’ invokes a sense of tragedy that sacrifice, spilled blood has been followed by greed.

In the yard of its own house

On the terrace of power

The pledge is dead

Strangled by its own greed

Another strong theme concerns the question of how Aceh can transition from its experience of endemic violence to a peaceful post-conflict society where rights are respected?

Now we are trying to cleanse

The wounds of history with peace

Do not let the bloodshed begin again!

By the traces of war that never cease

By the unshed tears that have never been wiped away

By the blood that is still oozing

And by the pain of the still open wounds

(Geleng Rapa’i Geleng)

This brought to mind the devilish choice articulated by Chilean writer Ariel Dorfman [iv] in contemplating building democracy and peace in post-Pinochet Chile. He asks whether, in a post-torture society, do you draw a line in history and then get on with it (as seems to be the approach in Aceh) or do you attempt to bring to justice the perpetrators of barbaric acts? Dorfman explored the terrifying possibility, if the former solution is chosen, that the tortured always faces the chance of coming face-to-face with the torturer–how can that be consistent with building peace and democracy? Zubaidah’s commitment to the necessity of a commission for peace and reconciliation subtly informs several poems.

The final poems turn to the Islamists that have captured the state in Aceh, and who are enforcing a specific kind of return to Sharia law which is targeted at women–their bodies withstanding, a new violent onslaught bodes. She summons the reader to embrace a refreshed struggle against this new threat:

The untreated and unhealed wounds of women are rent again in the process of the formalisation of Islamic law

Our womenfolk–who are still at the mercy of those champions

Who proclaim peace and

Spin prayers over their bodies

That they no longer own

(Aceh – My Homeland)

Kathryn Robinson is a professor of anthropology at the School of Culture, History and Language at the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific.

—

References

[i] Harry Aveling, ‘Indonesian Literature After “Reformasi”: The Tongues of Women‘, Kritika Kultura, No.8, ,2007, p.20 [ii] Michael Taussig is the author of Shamanism, Colonialism and the Wild Man Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987. He made this comment at a seminar in Sydney at which I was present during the writing of this book. [iii] Morgan, Robin The Demon Lover: the Roots of Terrorism, New York: Washington Square Press, 2001. [iv] This was the idea behind his play Death and the Maiden: A Play in Three Acts. London: Nick Hern , 1991 . It also became a film. Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss