Cakes, States and Civil Society

It is paradoxical that while most interpretations of civil society include autonomy from the state as a central characteristic, the groups most widely recognised as civil society are those legally sanctioned by the state, with the foremost among these being non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

Perhaps NGOs are to civil society what money is to an economy. While the former may be the most visible, quantifiable and accessible aspects, they only partially reflect or represent the larger whole.

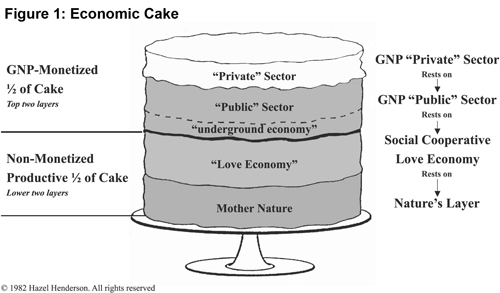

Iconoclastic economist Hazel Henderson has likened the total economy to a multi-layered cake, with the bottom layer being nature, from which all resources derive, and upon which all else depends.

The next layer up is the social or ‘love economy,’ containing the fundamental yet largely unremunerated functions of reproduction, subsistence, family and community.

The monetised economy begins only at the third tier, which is primarily comprised of the public sector, but also includes the ‘underground economy’ of illegal trade, corruption, and the like. Finally, the top layer, which might be the relatively thin icing, is the private sector.

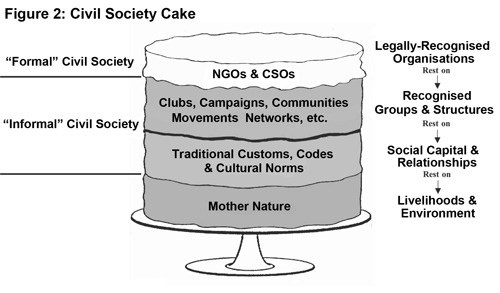

Extending the cake analogy to civil society, nature might again be the bottom layer. This is not to say that civil society includes the natural world, but the environment does both sustain and dictate livelihoods, which in turn determines the characteristics of the upper tiers.

The second layer also closely reflects Henderson’s cake, containing the ‘social capital,’ or relationships, traditions and culture that hold various groups and communities together and enables them to function. The boundaries, characteristics and functions of the different groupings in this layer are usually vague and often changing.

The third layer of the civil society cake is also more public, with memberships and objectives more clearly defined and widely known. These groups and networks, such as clubs, campaigns or movements, may have recognised rules, structures and leadership, although most have no legal status or function.

Together, the second and third layers constitute what might be called informal civil society, to which we will return below.

Formal civil society makes up the top layer, which includes NGOs and those CSOs (Civil Society Organisations) with a defined legal status.

It bears noting that while most definitions of civil society exclude the private sector (the parallel layer on Henderson’s economic cake), the distinct global trend is toward increasingly close collaboration between NGOs and business.

At least two further parallels can be drawn between the two cakes. Firstly, just as GDP growth and rising stock indexes do not necessarily indicate a strong, equitable or sustainable economy, NGOs and CSOs alone do not constitute a robust or representative civil society.

Secondly, a cake’s upper layers need the lower tiers for support and viability. Likewise, Henderson argues the sustainability of the private sector depends on the health of the more foundational economies. The same principles can be applied to civil society.

Customs, Culture, and the Roots of Civil Society

Returning to the second layer of our civil society cake, ‘social capital’ is usually defined as the relationships and networks that enable groups, communities or larger societies to function. When exogenous interests such as projects or sales campaigns strive to co-opt or utilise this capital to achieve their objectives, it is manipulative. But when those groups or networks act to pursue or protect their own interests, it might be described as civil society.

In this sense, the foundations of civil society are essentially self-interested and self-activated (or empowered) social capital.

Another way to envision these foundations, or informal civil society, is to ask what served to mediate within and among local groups and communities before the development of the state? What governs these groupings in sectors where the state is not involved, or in areas beyond the reach of the state? Thirdly, what governs in those areas where people don’t wish to be externally governed?

Historically (and in ‘less-developed’ counties), traditions and culture played (and play) a more central role in regulating local groups and communities. Examples are myriad, ranging from clan structures and village councils, to norms regulating the inheritance of property, to traditions for the conservation, management, sharing and tenure of common resources.

These diverse customs, religions, rites and taboos are part of locally understood, albeit largely undocumented, rules and codes. As noted above, such cultural norms and social structures most often extend from local livelihoods, which themselves reflect relations with the natural environment.

As a relatively small country of some six and one-half million people, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) is extraordinarily rich in such cultural diversity. From 50 to 150 ethnic groups speak scores of languages and dialects. While Buddhism is described as the primary religion, numerous forms of Animism likely play a much larger role in the beliefs and daily lives of most Lao citizens.

In addition, the history of Laos is one more of shifting kingdoms and feudal alliances than of a singular state or unified nation. French and US occupations had limited presence beyond the main towns and provincial centres, and the USSR-led, post-revolutionary campaign to collectivise the peasantry proved wholly ineffectual. Indeed, for much of the Lao PDR’s first decades, the people of the People’s Republic were advised to ‘kum tua ang,’ or fend for themselves.

In other words, until quite recently, most of the local populations of Laos have for the most part governed themselves, and it is suggested this has been done by what can be broadly described as traditional or informal civil society.

While far from perfect and often not equitable and just, such capacities for local governance have not been afforded adequate acknowledgement or respect. They are also in sharp decline.

Development and Destruction

Laos is second only to India in the number of native rice varieties, and the abundance and diversity of other indigenous crops and breeds is exceptional. These have been preserved, shared and adapted within and among communities and clans for generations to best meet local needs and conditions. However, they are rapidly being replaced by ‘improved’ varieties and non-food crops tailored to the demands of urban and commercial markets, while often bringing higher input costs, greater risks, increased competitiveness, and more debt to local producers.

Local trade and barter, which serve to build cohesion and preserve autonomy, are quickly losing ground to monetary transactions. Actively supported by most development policies and programs, such ‘integration into the monetized economy’ shifts focus away from localised self-reliance to dependence on more distant merchants and markets.

The role and authority of traditional leadership, village elders, and the like are being supplanted by positions or bodies either appointed or sanctioned by the state, such as mass organisations, village headmen, and various committees for mediation, schools and development projects, etc.

In a similar vein, local customs or mechanisms for the management and sharing of common land, forests and other resources are being replaced by laws and legal codes which local populations have limited understanding of and even less authentic access to.

Through various relocation and consolidation programs, nearly one-quarter of rural villages have ceased to exist in recent years. Groups of different ethnicities are often combined, with significant negative impacts on traditional social structures and forms of governance. These larger communities are also putting greater demand on local environments and dwindling natural resources, bringing further disunity and conflict.

Local culture and identity are losing out to competition, materialism and marketing. Youth look to the cities and television for role models. Most efforts aimed at preserving culture serve more to commodify and market it (though tourism, handicrafts, etc.) than as a resource for local empowerment.

Until quite recently, the wellbeing of most government officials depended primarily on their relationships within local society and secondary vocations. As such, they identified closely with local needs and priorities, and often functioned more as members of their community than as government staff. However, increased capacity cum state-building efforts, largely enabled through development aid, combined with growing opportunities for income through private sector initiatives and corruption, have brought a marked change in their sources of livelihood, security and therefore loyalty.

In each of the above examples, ‘development’ and concurrent state-building are displacing the focus and allegiances of populations from local cooperation and reliance to more-distant markets and mechanisms of governance over which those populations have significantly diminished control.

Subsistence, self-reliant economies and the foundations of civil society are giving way; decision-making and power are moving from local groups and communities to the state and the private sector.

A Focus on the Frosting: GDP and NPAs

The Lao government’s master plan for national development is almost entirely based on the growth of the monetized economy, or GDP, which relies primarily on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), that in turn centres heavily on the exploitation of natural resources. The strategy has also depended on substantial and continuing donor assistance, firstly in establishing the policy and legal framework to attract foreign capital, and secondly to help offset the shortfall in revenues available for public investment resulting from those policies.

As such, the government’s strategy continue to enjoy strong and steady support from the international financial institutions, as well as most large donors. At the same time, increasing concerns are being raised about the ‘resource curse’, economic and environmental sustainability, social inequity, corruption, land grabbing, public debt, and the like.

Henderson might describe it as the lower, foundational layers of the cake being sacrificed for the sake of more icing.

There also appears to be a similar focus on the uppermost tier of the civil society cake, with nearly all strategies and efforts for the development of Lao civil society centred largely or exclusively on CSOs.

Some descriptions and background analysis includes mass organizations such as the Front for National Construction, the Women’s Union, the Revolutionary Youth Unions, and the Federation of Trade Unions, describing them as quasi-civil society, or perhaps precursors to it. However, while the names of these state organs might imply a role in representing the people to the government, their actual function is usually the opposite.

Reference is sometimes also made to international NGOs. Nearly all INGO work, however, focuses on development, capacity-building and service provision that extends from and supplements official government policies, programs and objectives. Close adherence to this official agenda is assured through regular and lengthy government approval processes at the organisational, project and staff levels. Local officials are also closely involved in the implementation of nearly all field activities.

Less reference is afforded the fact that rights or advocacy-based CSOs are not allowed to operate in the country, and there are few active linkages between local groups and such international organisations, movements or networks.

Further, while most are single-purpose, often project-dependent, and play limited or no roles in broader advocacy, virtually no consideration is given to various business and professional associations, production and user groups, farmers’ organisations, and other local groups.

Finally, there is also little mention of those institutions that, while not usually considered part of civil society, are nonetheless fundamental in enabling it to function effectively. These include autonomous media, unions, religious and academic institutions and the like which, in large, do not exist in the Lao PDR.

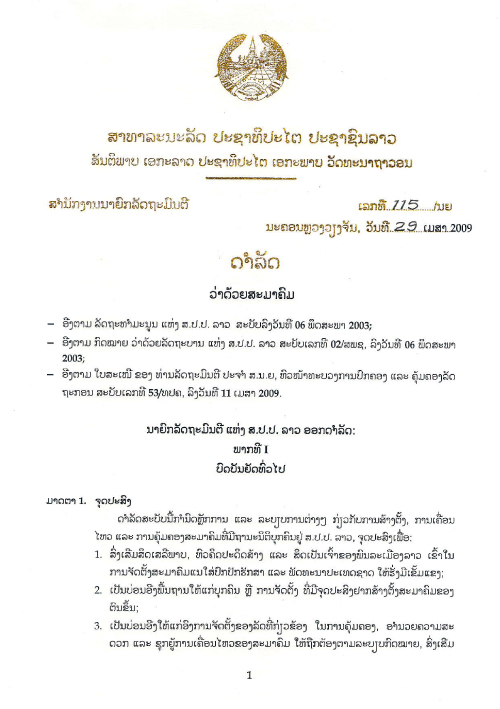

Among donors and in development circles, it seems most hopes for the future of Lao civil society rest with Decree 115/PM, which establishes the legal basis for Non-Profit Associations (NPAs) that are often described as the local equivalent of NGOs. This stretches the term ‘non-government’ to considerably new lengths.

Decree 115/PM, seen by many as the wellspring of Lao civil society

NPAs are required to go through a stringent approval process often taking well over a year. Founding committees and board members must undergo police checks, and association names, charters, goals and membership usually face significant changes before receiving approval. Thereafter, the regular submission of plans, budgets and reports for approval by central, provincial and often district levels is also required in order to continue operating.

While there may be some latitude for innovation in approach, there is very little in aim or objective. Even more than for INGOs, the intended purpose of NPAs is to assist in the realisation of government programs and policies, a fact that has been made even more explicit in a newer draft decree on NPAs and foundations.

Further, most capacity-building support for NPAs centres on project planning, proposal writing, financial management and the like, skills primarily needed to meet donor requirements. Torn between meeting the extensive needs of both government and donors, NPAs may have little time or resources left to respond to those of local populations.

The assertion is not that NPAs are not a positive step. But they are only one piece of a much broader landscape. It also bears repeating that the icing is only the surface of the cake, not its main substance. And as suggested above, the lower layers may well be crumbling.

Disappearance and Denial

While civil society, more broadly envisioned, is diverse, multi-faceted, often indefinable and sometimes imperceptible, if one were to choose a face for Lao civil society, it would be that of Sombath Somphone.

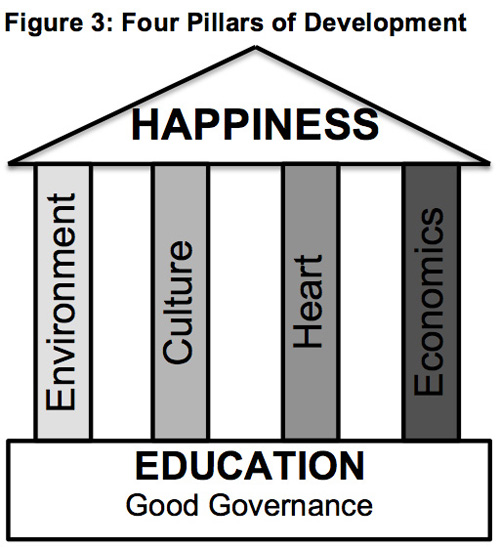

While working closely with the government for more than 30 years, he carefully nourished his autonomy. While not against modernisation, he advocated for the respect and preservation of local community, culture and identity. While not opposed to economic growth (GDP), he spoke of the more primary goal of happiness (Gross National Happiness, or GNH). His four-pillars of development model has many similarities with the economic and civil-society cakes described above.

His work in agriculture focussed on increasing production, balanced with sustainability and self-reliance, and his efforts in education on critical, independent thinking, balanced with respect and responsibility. His work first with the Rice-Integrated Farming Systems project and then the Participatory Development and Training Centre (PADETC) broke ground for both Lao citizens and international organisations working in Lao development.

Sombath recognized the deep-rooted and multi-layered nature of authentic civil society.

He was the first and only private Lao citizen to win the prestigious Magsaysay Award. He also served as Co-Chair on the National Organising Committee of the Asia Europe People’s Forum (AEPF). Together with consultations assessing local aspirations throughout the country that preceded it, the forum was hailed as a landmark for Lao civil society.

And then Sombath disappeared. Taken from a police post on a busy Vientiane street, in full-view of CCTV cameras.

The reaction was both swift and extreme. While the voices of concerned individuals, groups and governments around the world grew, those within the country fell silent.

Although a few INGOs working in the country sent an early letter to authorities offering assistance, no further public statements or expressions of concern followed. Requests by family members to post missing person notices on office bulletin boards were usually refused. Excepting mundane logistical coordination, open exchanges among staff fell as rumours and distrust rose. Some Lao staff chose to leave the country for a period.

The silence has been most notable among the larger agencies most able to speak up, and particularly among those most vocal in promoting their efforts toward the development of Lao civil society. The United Nations Development Program, which worked closely with Sombath leading up to the AEPF, made no mention of his subsequent abduction. Eleven months later, while the European Union and several diplomats raised concerns at a national roundtable meeting, the INGO network was unable to mention Sombath’s disappearance, his work or even his name in their collective statement. None of the agencies who have worked most closely with Sombath over the years make any mention of his plight on their websites.

Civil society–albeit in Myanmar–speaks up for Sombath

While regional media and human rights groups became active, nearly all Asean governments did little. Asean itself and the Asean Intergovernmental Committee for Human Rights (AICHR) did nothing. The principle of non-interference has been invoked on numerous occasions, even while often controversial foreign investments in Laos from those same countries rose to new heights.

Further afield, while academics in Australia expressed strong concern, only a handful of participants attending a Lao studies conference in the US agreed to publicly sign a statement of support, and the event’s organisers added a clause disavowing any association with the document. Similarly, many US INGOs working in Laos declined to sign a private, confidential letter urging President Obama to raise the issue at an upcoming Asean conference.

With few exceptions, INGOs involved in development have sought to distance themselves from this and other rights violations. Similarly, while UN rights bodies have repeatedly raised concerns, their sister agencies working in development have said virtually nothing. At the bi-lateral level, while diplomats have spoken up, development programs continue unaltered, except that several have increased their assistance.

Many argue that Sombath’s abduction is a matter of human rights, and hence not related to development work. Others assert that open advocacy for his case or other rights issues may threaten or disrupt that important work.

This raises troubling questions.

A Brief Summary

The Lao PDR, with significant financial and technical support from international donors, has pursued a rather narrow emphasis on the development of the private sector and monetised economy. While this has brought remarkable growth in the GDP, there have been detrimental effects on the more fundamental economies, including debt in public economy, inequity in the social economy, and destruction of the environmental economy.

There appears to be a parallel, top-heavy strategy in regard to Lao civil society, with focus almost exclusively on its most visible and accessible aspects–CSOs in general and NPAs in particular. While the Lao government is consistent in holding these agencies as service delivery mechanisms to further its development policies and programs, there is far less congruence between the rhetoric and the actions of donor and development agencies.

The vitality and self-reliance of the more foundational or informal aspects of civil society are being weakened, in large part through state and capacity-building efforts supported by donors and development agencies. While failing to recognise or acknowledge this, many of these same actors assert the basis of and hopes for Lao civil society rests with the development of more formal CSOs and NPAs. However, as the space for these organisations to fulfil roles as part of a broader and more viable civil society is increasingly constrained and threatened, those same donors and development agencies remain largely silent.

A Few Questions

- Where are the authentic roots of Lao civil society? Are there parallels between local, self-reliant economies and informal civil society?

- On balance, are donor and development agencies contributing more toward the development or the destruction of Lao civil society?

- Are most capacity building efforts for local CSOs primarily aimed at meeting the needs of government, donor agencies, or local populations?

- What is development without the recognition of people’s rights, or advocacy for those whose rights are being violated, often through those development efforts themselves?

References

Asian Development Bank, Civil Society Briefs: Lao People’s Democratic Republic, 2011.

Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014-Laos Country Report. G├╝tersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014.

Delnoye, Rik, Survey on Civil Society Development in the Lao PDR: Current Practices and Potential for Future Growth, SDC Mekong Region Working Paper Series. No 2, Vientiane, Lao PDR, 2010.

The Economist, Civil Society in Laos: Gone Missing, 08 January 2013.

Fair Observer, Laos: Silencing Civil Society, 04 February 2013.

Kunze, Gretchen, Nascent Civil Society in Lao PDR in the Shadow of China’s Economic Presence, in Global Civil Society: Shifting Powers in a Shifting World, Heidi Moksnes and Mia Melin (eds.), Uppsala: Upsala University, 2012.

Ministry of Home Affairs, Draft Capacity Assessment Report, October 2013.

Oxfam International, Laos’ emerging civil society: challenges and opportunities, 2014.

Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, Civil Society Project, July 2012.

Randall Arnst has spent most of his adult life in Southeast Asia, particularly in Thailand and the Lao PDR.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss