Australia must meet Timor-Leste halfway over their disputed sea border and the lucrative oil and gas reserves that lie beneath, writes Ines de Almeida.

In The Hague a United Nations Conciliation Commission has begun its work to help settle a long-running dispute between Timor-Leste and Australia — a dispute over where the sea border between our two nations should be.

International law of the sea states that where the coastlines of neighbours are less than 400 nautical miles apart, the sea border between nations should start halfway. This is a simple principle, easily understood and defined clearly.

But this principle has been opposed, ignored and discarded by Timor-Leste’s neighbour and friend Australia for more than 50 years, and there is a plain and obvious reason for this: wealth from oil and gas in the Timor Sea.

In the 1960s, well before any sea border between Australia and Indonesia, long before Timor-Leste’s former colonial ruler Portugal took Australia to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) over the Timor Gap, and before Indonesia invaded East Timor, private companies, licenced by the Australian government, were exploring and confirming the presence of vast oil and gas reserves in the Timor Sea. Portugal objected.

Some of these resources are currently being tapped, but other oil and gas reserves known as Greater Sunrise — valued at more than US $50 billion — are yet to be exploited. It’s this oil and gas beneath the Timor Sea that is driving the Australian government’s treatment of Timor-Leste.

If the sea border between Australia and Timor-Leste started at the median line, consistent with international law, then the oil and gas reserves would be the property of the people of Timor-Leste.

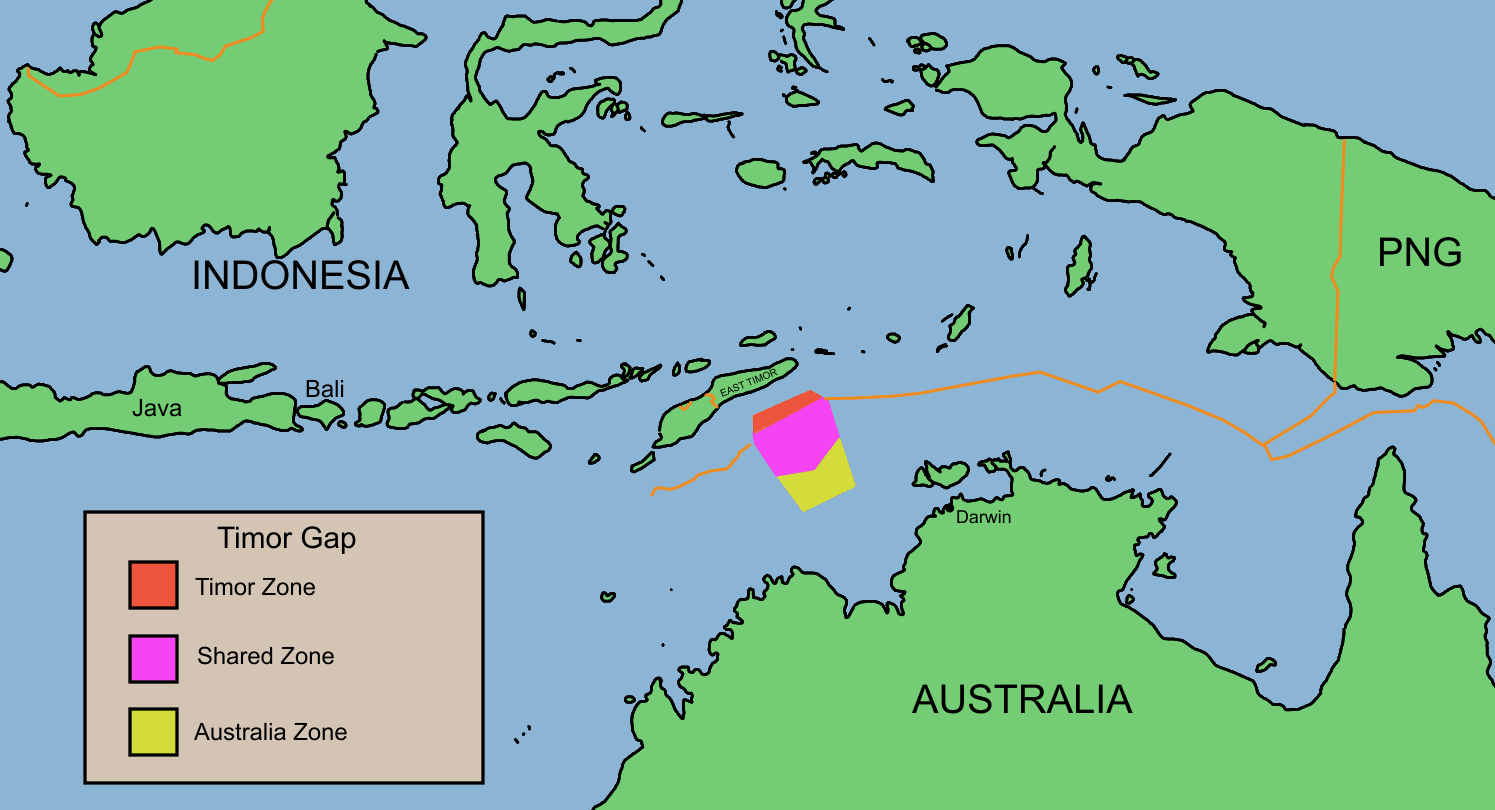

That is why Australia has no interest in discussing a fair sea border with Timor-Leste, and instead clings to a joint provisional arrangement, the Treaty of Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS), which Timor-Leste says is void, dead, and has not worked. CMATS corrals the oil and gas reserves in a “shared” zone, but in reality resources are far closer to the shores of Timor-Leste than they are to Australia.

When independence was restored for the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste in 2002, our new state was not just struggling to find its feet after Indonesia’s brutal 24-year military occupation — as a people, we were gasping for air.

What Timor-Leste needed most was full nationhood with undisputed national borders – both land and sea – so like other countries, we had sovereignty over our natural resources and the opportunity to commence rebuilding a secure, healthy and prosperous nation.

This, however, was not a common goal.

Leading up to our independence, Australia made it clear to Timor-Leste where it wanted the sea border. The Australian position was unacceptable to Timor-Leste.

Laying the groundwork for what was to follow, in March 2002, Australia quietly withdrew from the binding dispute resolution mechanism under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ), specifically on the delimitation of maritime boundaries.

On the very day of the restoration of our independence, we were faced with having to sign the Timor Sea Treaty, the near mirror image of the 1989 Timor Gap treaty struck by Australia and Indonesia over our sea territory when we were illegally occupied.

Signed in May 2002 and valid until 2057, and covering joint petroleum development in Greater Sunrise, the Timor Sea Treaty served to maximise Australia’s advantage and commercial interests and to keep its foothold in maritime territory that was not theirs.

It’s now clear this was the plan all along. When you add together all of the Australian government action on this over the years, it is difficult to conclude otherwise.

First, there is Australia’s longstanding refusal to negotiate a fair, median line border, despite Timor-Leste’s justified protestations. The history demonstrates this refusal.

Australia’s insistence instead on the Sunrise International Utilization Agreement and then CMATS, which deals Australia into oil and gas income from reserves in the Timor Sea far closer to Timor-Leste than Australia and, tries to stop us from having our maritime borders.

Then there’s Australia’s premeditated withdrawal from the dispute resolution mechanisms of UNCLOS and the ICJ in March 2002. Australia was vulnerable to the risks implicit in UNCLOS and the ICJ from its experience in 1989 when Portugal took Australia to the ICJ.

And of course, the Australian Government’s decision to spy on Timor-Leste’s officials during critical commercial, intergovernmental negotiations on the Timor Sea – a sinister miscalculation and a step too far.

In the years since securing independence, the people of Timor-Leste have worked hard to develop our economy and to lift health, housing, and education standards. But it takes time to rebuild a country after 24 years of war and occupation.

Timor-Leste is one of the youngest and poorest nations on earth, still receiving massive amounts of international aid each year and where 41 per cent of people live on US $1.25 a day.

By initiating the conciliation process now under way in The Hague, Timor-Leste is seeking to bring Australia to the negotiating table so that we can settle our dispute and agree on a sea border starting halfway between our two nations.

This stand-off is painful. Many Timorese have deep ties and love for Australia, despite their resources grab.

Ines de Almeida is the Campaign Director for Time to Draw the Line.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss