On 8 December, about 60,000 people gathered near Dataran Merdeka in Kuala Lumpur to protest the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government’s plans to ratify ICERD (the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination). The rally marked the culmination of a successful campaign against ICERD stoked by PAS, UMNO, and other Malay Muslim organisations, which claimed that ICERD would undermine the Malays’ special status and the role of Islam in Malaysia.

That campaign was successful even before this month’s protest. After an anti-ICERD backlash gained volume on social media and in street protests across Malaysia throughout October and November, the government publicly announced on 24 November that it would not ratify ICERD. Perhaps inspired by Indonesia’s 212 Reunion movement, an anniversary gathering that commemorates 2016’s anti-Ahok rallies, the organisers of the anti-ICERD rally renamed it Himpunan 812 (8 December Gathering) to celebrate the “success” of the anti-ICERD movement.

So who participated in Himpunan 812, what were their concerns, and how have they been mobilised?

For sure, not all of the rally-goers were outright racists nor narrow Islamists. But many of them did, to differing extents, support a Malay-dominated leadership and/or an Islamically-oriented government. In this sense, the most immediate comparison is with Himpunan 355 in 2017, which saw a crowd of about 30,000 gather in KL to demand more extensive application of Islamic law in Malaysia. Almost all participants at both Himpunan 812 and Himpunan 355 were Malay Muslims. Yet while Himpunan 355 had a clear Islamic agenda, Himpunan 812 used ICERD as a rallying point to bring together various forces of Malay nationalism and Islamism, as well as ordinary Malay Muslims who are not happy with the ruling PH coalition. This was illustrated by the mix of messages I saw expressed at the rally, from Hak Melayu: Jihad Jalan Kami (“Malay Rights: Jihad is our Way”) to Islam Memimpin (Islam Leads), and the variety of personal appearances, from women in niqab (full face veils) to men in silat (martial arts) attire.

Author photo

And while the Himpunan 355 crowd were mainly PAS supporters, Himpunan 812 attracted participants who were not necessarily aligned with the party. From my estimation, more than half of Himpunan 812 were indeed mobilised by PAS. But the protest also attracted significant numbers of UMNO supporters, members of ISMA (Ikatan Muslimin Malaysia, a conservative Islamic NGO), and followers of other smaller Malay and Islamic groups. Behind the organisation of Himpunan 812 were two loose coalitions of NGOs, Ummah (Gerakan Pembela Ummah) and Daulat (Sekretariat Kedaulatan Negara)—the former targeted at more Islamic-oriented groups, while the latter aimed at more Malay-centric groups. ISMA, whose stated aim is to uphold both Malay and Islamic agendas, was perhaps the key organisation that brought together UMNO and PAS, as well as various Islamist and Malay nationalist groups in the rally. It is also one of key forces behind the very active social media campaign for Himpunan 812.

There are two points to emphasise at the outset. First, while, for analytical purposes, I use the terms “Islamist” and “Malay nationalist” to refer to the various organisations involved in Himpunan 812, I don’t mean to imply that these categories are mutually exclusive. PAS supporters emphasised the Islamic agenda but they also championed Malay issues, and UMNO supporters highlighted Malay agenda but they also used Islamic idioms, while ISMA strategically combined both the Islamic and Malay agendas together. Second, while I don’t claim that my observations are representative of the rally as a whole, I aim to provide such insights as I can based on those observations.

Author photo

A convergence of Malay-Muslim grievances

Naturally, Himpunan 812’s role as a platform for diverse Malay-Muslim causes and grievances invites comparison to the Aksi 212 in Indonesia. ISMA itself was not shy about drawing explicit links between the Malaysian and Indonesian mobilisations: in a convention held two weeks before the rally, ISMA invited Ustaz Bachtiar Nasir, a leader of Aksi 212, to speak via video call. The day after Himpunan 812, a Facebook page linked to ISMA uploaded a photo that combined images of Reuni 212 in Jakarta and Himpunan 812 in Kuala Lumpur, with a caption entitled “Kebangkitan Ummah Nusantara” (the awakening of the Nusantara ummah).

Image shared on “Pengundi Sedar” Facebook page

Despite such rhetoric of “Ummah Nusantara” and similar mobilising strategies, Himpunan 812 and Aksi 212 do not share a unifying transnational Islamic agenda. These two movements are strongly linked to the political competition in both countries. Instead of being based on a coherent ideological discourse, their mobilisations for “Muslim unity” are contingent, and based on there being a common perceived enemy—Ahok in Indonesia and “ICERD” in Malaysia.

Nevertheless, the Islamic tone of much of the rally was clear. Most striking was the sight of a few black and white tauhid flags (flags bearing the Islamic creed), that are near-identical to the symbol of Hizbut Tahrir. These flags are new to rallies in Malaysia, and might have appeared for two possible reasons. First, because of inspiration from Aksi 212 in Indonesia, in which some embraced the flag as an “Islamic” flag, especially after the ban of Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia. Second, because some PAS supporters tried to appear less partisan by using a more generic “Islamic” symbol instead of the PAS logo. I talked to a few participants carrying the tauhid flags, and they appeared to have no idea about its purported association with Hizbut Tahrir, merely viewing it as an “Islamic flag”. There were also signs of the increasing use of Islamic idioms by some Malay nationalist groups, too. One group of middle-aged men and women marched by while holding UMNO flags and chanting “Allahuakbar”. Another huge flag bearing the term “Pemuda Shah Alam” combined UMNO insignia with the Islamic creed and a sword [see below].

Hybrid UMNO-Islamic flag. Author photo

PAS supporters appeared to be the most tenacious supporters of the rally. The more I walked towards the centre stage of the rally in front of Dataran Merdeka, the fewer UMNO flags I saw and the more I encountered PAS supporters. While some people were already leaving as early as 3pm (I assumed they were mostly UMNO supporters who had little experience in demonstrations), most PAS supporters stayed until the end of the rally, and they appeared to be friendlier to me—perhaps because many of them would have participated in Bersih rallies together with non-Malays, when PAS was in the Pakatan Rakyat coalition.

I had a short conservation with one young man who said he was a PAS member living in Petaling Jaya, and who preferred to speak to me in English. He emphasised that he was “not racist… Islam teaches against racism… But in Malaysia, there is an income disparity. Chinese are richer. Malay are poorer… Unlike in other countries, in Malaysia, we can have Chinese schools and now we have a Chinese finance minister…Do we Malay really discriminate Chinese?” He continued, “This rally is not only about ICERD. We have been facing many challenges since GE14…Some people want to recognise UEC (United Education Certificate, a Chinese-language secondary school qualification). Some want to promote LGBT rights. These are against our constitution. We are here today to uphold our constitution”.

Author photo

The attendance of various fringe, often regionally-based, Malay groups is a trend that deserves further attention. The rally was scattered with multicoloured flags belonging to organisations from Pekida (Persatuan Kebajikan Islam and Dakwah Islamiyah Malaysia, a right-wing Malay group that uses Islamic idioms to defend Malay rights), to “Ninja Society Malaysia”, presumably a Malay youth subculture group. A few Malay men wearing black T-shirts displaying “Empayar 313 Tanah Melayu” and swords. As an online search indicated, “Empayar 313 Tanah Melayu” is a small Malay ultra-nationalist group. Another group carried a yellow flag reading “Dewan Muda Johor”, presumably a new Malay youth NGO based in Johor. I talked to a group of young Malay men wearing t-shirt bearing “Tanah Tumpah Darahku GGS” on the front and Islamic creed with a sword in the back. As one of them told me, GGS is Geng Gerak Sahur, a local community group in a village near Teluk Intan, Perak. GGS runs activities such as gotong royong and Islamic studies sessions. During Ramadhan, the group members patrol around the village and wake the residents up to have sahur, a meal eaten before the beginning of fasting.

One GGS member said they were non-partisan and that they voluntarily organised three buses from Teluk Intan to KL to support Himpunan 812. Not surprisingly, he learned about Himpunan 812 from social media platforms such as Facebook. He shared the concern of many villagers that “the government is cutting various subsidy for the poor, for the fishermen and for the farmers…”. He continued, “we do not really know what ICERD is… But we feel that the current government does not care about the plight of Malay Muslims. That is why we come to show our support today”.

GGS members. Author photo

Before I finally left the rally, I talked to another group of young Malays who said they were from Kedah. One pointed to his friend next to him and explained that “his parents and him were PKR members. He joined Bersih rallies before and now, he is with us”. His friend told me that he indeed joined a few Bersih rallies and joked that “I am always against the ruling government”. He compared Bersih rallies with Himpunan 812: “Bersih,” he said, “has many Chinese… This rally is almost all Malay. I feel more semangat (spirited) in this rally because we are all Malays. But, no, I am not a racist…”.

The influence of popular preachers and their social media presences in mobilising crowds and shaping Muslim opinions also warrants examination. One group of participants carried two flags together: a PAS flag, and another reading “Geng Usrah Ustaz Ahmad Dusuki”. Together with Ustaz Azhar Idris (who was present at the rally), Ustaz Ahmad Dusuki is another popular PAS-affiliated preacher who endorsed Himpunan 812. He posted a video of Reuni 212 in Jakarta on his Instagram; this video was widely circulated on social media and WhatsApp groups on the same day of the rally, and some mistook the images from Jakarta as showing the scene of Himpunan 812. A day after the rally, Ustaz Ebit Lew, an ustaz who often avoids political topics, praised the rally on his Facebook. Meanwhile, the outspoken Perlis Mufti Dr Maza gave a mixed response towards the rally—not fully endorsing it, yet viewing it as “relevant”.

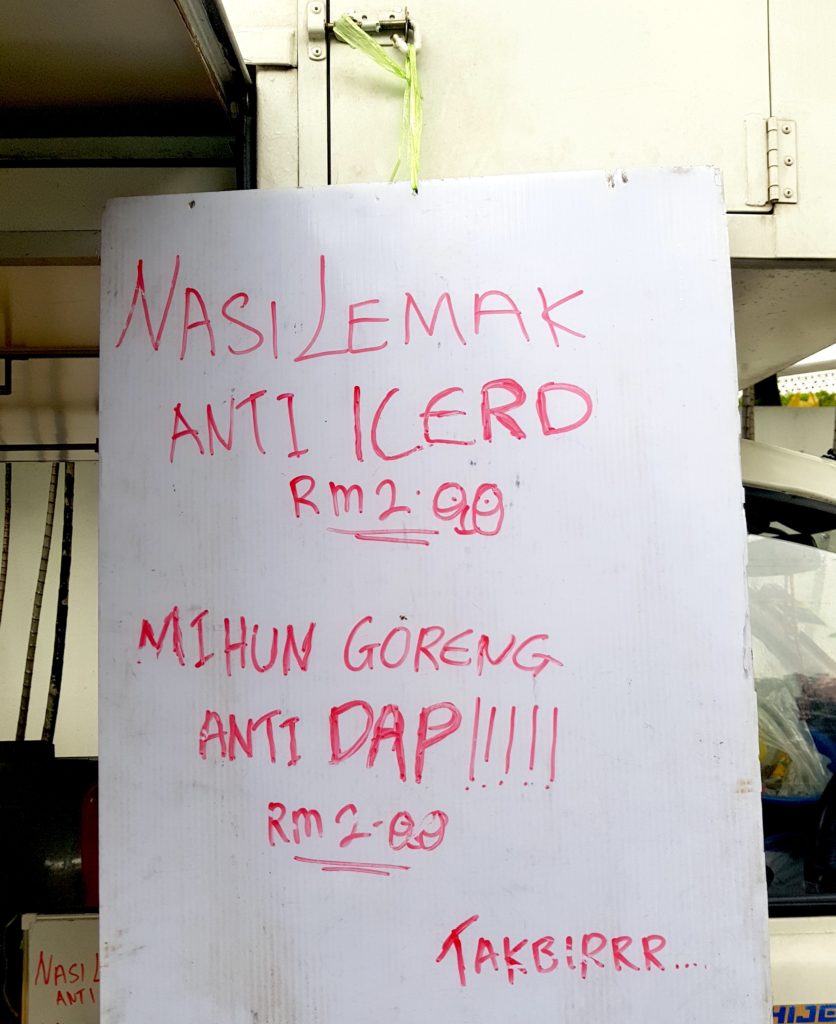

Like many other PAS rallies, Himpunan 812 was a good business opportunity for many small and medium-sized Malay entrepreneurs. At the compound in front of Masjid Negara, there were many stalls selling “anti-ICERD” T-shirts, foods, drinks and other merchandise. Author photo

A new rivalry in Malay politics?

As these conversations revealed, behind Himpunan 812 was a combination of social media influences and peer pressure, an intersection of economic insecurities, political uncertainties, and ethno-religious sentiments. A desire to champion Malay Muslim rights was also combined with an emphasis on appearing “non-racist” among the rally participants. While rejection of ICERD was the ostensible rallying point, Himpunan 812 was definitely about more than a UN human rights instrument. Instead, it is the result of accumulation of various issues that have been raised and perceived as “against the interest of Malay Muslims”, such as recognising UEC, bilingual street signboards, Oktoberfest, LGBT rights, and so on.

Himpunan 812 points to a new configuration of old politics of race and religion in post-GE14 Malaysia. As such, Himpunan 812 is less about how or whether the ICERD ratification will challenge Malay Muslim rights. Instead it is more about shaping perceptions and discourses among Malay Muslim that PH government is “anti-Islam” and “anti-Malay”. It also reflects economic insecurities among segments of Malay Muslims—insecurities that are not just about the gap between the rich and poor, but also about the competition among the middle classes.

Author photo

A huge banner reading “Melayu Sepakat, Islam Berdaulat” (“Malays united, Islam sovereign”) spoke to the importance of unity among various Malay political parties and organisations amid perceived threats. Yet the Malay Muslim unity seen at Himpunan 812 was a contingent and a strategic one. It was not based on a coherent ideological discourse. Instead, it was based on common perceived enemies, such as the Chinese-majority DAP and Minister for National Unity and Social Wellbeing Waytha Moorty. Himpunan 812, therefore, is not primarily illustrative of the so-called culture war between “liberals” and “conservatives”, or between those who support “non-racial” politics and those who campaign for “Malay dominance”. Instead, it reveals the huge range of opinions between these two ends of the Malay-Muslim political spectrum, and how the organisers successfully brought together these different voices.

Notes on 212 in 2018: more politics, less unity

The second reunion of the 2016 anti-Ahok rally was a show of force from FPI ahead of elections.

With such competition as a background, the aim of Himpunan 812 was to swing Malay opinion towards this PAS-UMNO-ISMA coalition. Whatever the case, even within this exclusivist, anti-PH coalition there are obvious tensions. Such a formation may set up PAS to be the biggest winner: while it has the potential to capture UMNO voters, UMNO is losing its centrist credentials by moving further to the right. Hence the uncertainty about how this coalition of opposition of Islamist and Malay nationalist parties will evolve. But it is quite certain that racialised politics are here to stay in post-GE14 Malaysia. Just like in Indonesia, Malaysia is facing a challenge of how to deal with the politics of race and religion in a democratising state in the age of social media.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss