Julia Mayer reflects on a traditional Burmese performance by the legendary Shwe Man Thabin Theatre.

The monsoon in old Rangoon is a show-stopper in itself.

But at Yangon’s Kandawagi Lake and surrounding park, in an enclosed bamboo-woven theatre, which is this season’s home of Myanmar’s longest and continuously-running theatrical troupe, Shwe Man Thabin Dance Theatre, I am in for a performance like no other.

Our highly anticipated performance, sold out months in advance, is a panorama of music, dance, drama and human marionette puppetry that has been welded together to produce an epic five-and-a-half hour variety show. A visual spectacular, replete with several changes to the dazzlingly embellished and embroidered costumes, Myanmar’s zat pwe echoes the beautiful past imagined, reverberating contagious charm and charisma. It quite simply lifts the spirits.

A family affair

Zat (story) pwe (show) were traditionally performed by highly-trained travelling performers in villages all over Myanmar. Whereas the monasteries were once the centre of intellectual learning, traditional arts academies sprung up in the urban centres of Mandalay and Yangon, producing talented travelling troupes headed by a mintha, a male star who was often accompanied by his female counterpart the minthamee. One mintha who widely captured the hearts and the imagination of his audiences was Shwe Man Tin Maung, who founded the Shwe Man Thabin Dance Theatre in 1933 — to this day it is Myanmar’s most beloved and revered troupe.

Each of Shwe Man’s five sons Nyunt Win, Win Bo, San Win, U Win Maung and Chan Thar, were all highly accomplished minthas themselves, a couple going on to become luminaries of Myanmar’s stage and screen. U Win Maung has taken the art form to New York City, and more recently Kuala Lumpur and Singapore. More than 80 years later, the second generation of brothers are handing over the proverbial strings to the third-generation, with a fourth-generation mintha on the rise who, at the tender age of three, is already treading the floorboards.

Fondly referred to by his nickname ‘Putu’, Shwe Man Thabin Theatre’s brightest star on the horizon already has a large fan-base who orbit around the pint-sized performer to pin sizeable denominations of Burmese kyat notes. In a single performance, Putu can make over US$300, which is saved towards a future college fund. With bills fluttering fan-like from his intricate costume, Putu is already an accomplished performer who captivates his audience with his routine of feigning boredom, mock yawning, forward rolls and some fancy footwork to boot — or to slipper in this case.

Zat pwe through the ages

Shwe Man Thabin Dance Theatre has the contemporary audience at heart which largely explains how it has survived. It has moved with the times. Officially dating back to the 1800s, zat pwe performances under royal patronage primarily revolved around extravagant court dances and the retelling of the jatakas, stories relating to Buddha’s past in India, often as form of moral instruction. Despite the British disposal of the royalty in 1885, the emergence of Burmese cinema, which thrived in abundance until the outbreak of World War Two, the TV music video era, and the relentless advance of karaoke across Southeast Asia, zat pwe has survived against all these odds and politically sanctioned ends, to continue to be Myanmar’s most popular and renowned entertainment today.

Unshackled from its glorious royal connections, zat pwe made a return to its folkloric roots in the first half of the 20th century. But as an upwardly nose-turning middle class began to materialise and started to connect tradition with decadence, changes were necessary to retain audiences.

One of the more significant changes was to seamlessly incorporate short contemporary dramatic plays addressing the modern-day realities of family-related issues, the ever increasing class-divide, and petty politics with the traditional and enduring themes of love, loss and longing. The show I saw was an 80-year-old classic romantic story about a diamond dealer titled ‘Aww Meinma Meinma’ (O Woman). It has been given a facelift, in which the deep wrinkles of deception, deceit, and desire are flattened out to produce an updated slapstick comedy, leaving us wanting more.

Another way to reclaim audiences was to embrace new and evolving technologies, adding further to the visual extravaganza that makes a contemporary zat pwe a dizzying and sometimes overwhelming experience. Today, a zat pwe held in Myanmar’s urbanising centres comes with the expectation of lurid ever-changing high-definition backdrops of rose gardens, verdurous countryside scenes, temples, and noteworthy stupas.

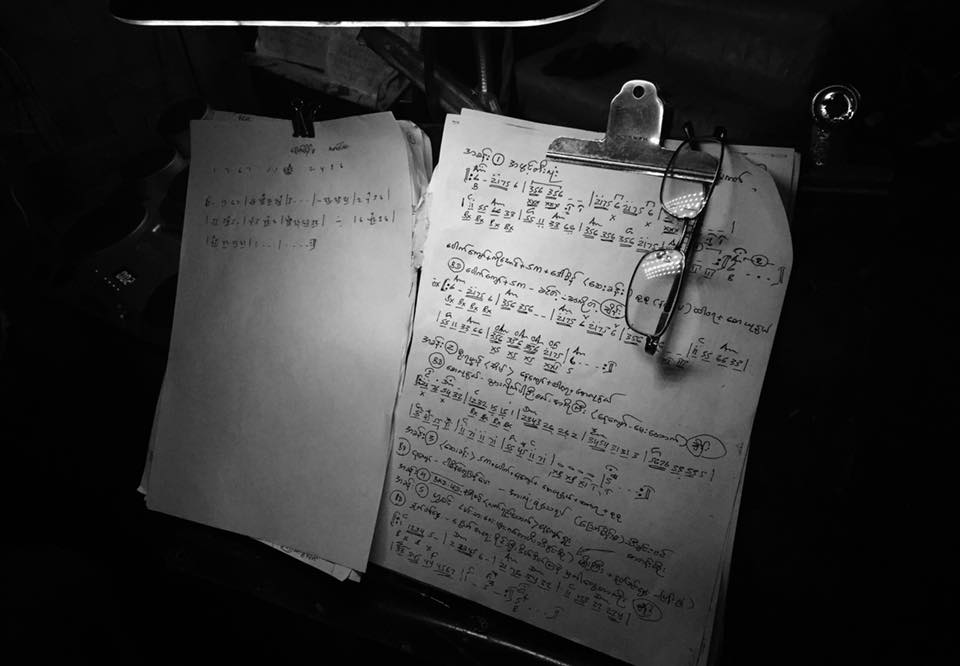

Backstage, amid the labyrinth of elevated costume-changing stations, a first rate audio-visual sound system is operated from multiple screens, dimmer boards, consoles, and mixers. Behind them is a five-piece electronic band which keeps in sync to the visible and highly-acclaimed traditional percussion orchestra, the hsaing waing, located inside the theatre to the right of the audience.

Exquisite cacophony

There can be no zat pwe without a percussion orchestra, renowned in its own right.

From the intricately carved golden concentric circles of the orchestral pit, the music and sound effects of the traditional hsaing waing ensemble is made up of an astounding array of drums, gongs and an oboe. The ensemble, much like the films from the ‘silent era’, simultaneously drives and responds to the action taking place on stage.

Exceedingly loud, wilfully wild at times, yet mostly melodic, the contrasting tempos, the intuitive style and technique of those highly accomplished and much-loved musicians are often juxtaposed to the soft, languid moves of female dancers to the quieter moments of the play. Yet, in lending an alien ear to the cacophony of roaring drums, the rising shrills of brass kettle gongs and the solitary mournful wail of the oboe, one soon realises that these sounds not only denote action being performed but also work as premonition in which a well-trodden, though often unscripted plot, is left wide open to chances, for better or for worse, but usually for the best.

While the music and sound effects appear to be primarily concerned with action in order to predict the future, the sheer mastery of these musicians is also their tacit ability to reflect the inner thoughts and feelings, as well as the spontaneous movements, largely improvised by the actors and the dancers. As much as a discerning ear is integral to the cohesion of the performance, a sharp eye is essential to keep abreast of the action, as well as the imagination to empathise with the tumultuous thoughts and feelings of the characters.

Back to the future

As Myanmar begins to open up, one might consider how this could affect the traditional cultural heritage of zat pwe and whether a diminishing audience is on the cards. As before, zat pwe has rolled with the changes, embracing them if not being the change-maker in itself. With the proliferation of social media in Myanmar, the proximity between the audience and performer has narrowed considerably, bridging the gap between the legends of zat pwe and their highly appreciative, adoring audience. It would appear that the very opposite is occurring with more and more fan sites being developed by ardent followers in honour of the troupe and its stars. Could this surge in the immense popularity of this theatre compromise the creativity rooted in profound devotion? It would seem, at present, that the selflessness and the dedication of the performers holds the promise that it will continue much in the same vein.

Behind the drawn curtains on tonight’s performance, the performers remain on stage to offer prayers of gratitude. Making an offering is by no means unusual in Southeast Asian dance and theatre performances — indeed it is often performed as part of the show. In this case, however, it is both a private and shared ritual in which the performers selflessly acknowledge that they are merely vessels from which great talent emerges. Just as with pure love, here, there are no strings attached.

Julia Mayer is a Masters of Museum and Heritage Studies student at the Australian National University. She has lived in Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and South Korea, and has written extensively on traditional arts, performances and cinema in the region. She is also the Asia Correspondent for Metro Magazine Australia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss