On 24 May 2009, I attended the first of two days of the “People’s Alliance for Democracy Assembly” at Rangsit University. Its main purpose was to assess the political situation and prepare a decision about whether to turn the social movement, at least partially, into a political party or not.

With my registration, I received a booklet that summarized the People’s Alliance for Democracy’s (PAD) “new politics” and discussed questions concerning the establishment of a political party. Participants also received a four-page questionnaire with 22 questions. The result would be used to gauge the PAD supporters’ view on whether a party should be established. For example, respondents were asked:

- What profession could you most appropriately represent? (This might reflect PAD’s proposal to have members of occupational categories elect a certain number of MPs proposed by occupational associations.)

- Do present politics respond to the aspirations of the heroes who have sacrificed their lives and blood to change politics for the better?

- Do you think that present politics can lead to new politics?

- If you think that the present political parties cannot lead to new politics, do you think that the PAD should proceed with its intention or not?

- Which group do you think can truly create new politics? (Options: PAD; others-specify.)

- By which means do you think can the PAD successfully create new politics? (Options: continued protests, setting-up a political party, others-specify.)

- Do you know that protests are a constitutional right, and that politicians try to pass a law about protests to restrict peaceful assembly, regarding both their duration and their locations?

When I arrived Sondhi Limthongkul was on stage. Somkiat Phongpaiboon, Phiphob Thongchai, and Chamlong Srimuang followed him with more or less inspirational addresses. Their content was rather simple — the current crop of politicians was mostly evil and corrupt. Therefore, new politics was needed to enable good people to administer the country, and prevent bad ones from having power (this is a cliché derived from a piece of royal advice). Since the current political parties would not do anything to change Thai politics for the better, the PAD had to get into the parliamentary ring.

There was not anything much of a debate in the formal part of the assembly. Rather, after the speeches of the core leaders, other participants would merely deliver their separate statements. Yet, there were certainly many informal talks about politics (and other issues) among the assembly members.

For a while, I talked with the chairperson of the PAD from one province in central Thailand. Being curious what a farang was doing at the meeting, he had approached me (I saw only one more farang at the event; he was in the yellow camp). He was quite confident that a PAD party could win constituency MPs. For example, the two Democrat party MPs in his province, he claimed, had been elected with the help of the PAD. His view on the UDD (the “red shirts”) was simple: There were two groups within the UDD, namely those who were bought by Thaksin, and those who lacked the correct information. From this perspective, information seems to have an essential quality, and it allows for only one possible opinion. Democratic pluralism, obviously, is difficult under such circumstances.

Since the chairman was a little agitated, I could not resist the temptation to suggest that the 193 days of protests had had little practical political effect. Visibly surprised by this suggestion he attributed the disqualification of Samak Sundaravej from the position of prime minister by the Constitutional Court to the PAD’s pressure “from below.”

While I was approaching the queue for lunch, a man asked me to move ahead of him. He was also curious about what I was doing at the meeting. Thus, I introduced me as a researcher, who was collecting data on the PAD and the UDD by using a social movement approach. Treating the PAD as a social movement immediately convinced him. However, using the same approach for the “red shirts” seemed strange to him. How could they be a social movement in the same category as the PAD (after all, the usual cliché is that the reds are merely thugs and ignorant villagers hired by Thaksin to save his skin)? We then compromised by saying that the PAD and the UDD had both similarities and differences.

Images (click on the images for a larger version)

Title page of Sondhi’s newspaper ASTV Phuchatkan of 25 May 2009, saying that the PAD assembly had given the green light to establish a political party.

This cartoon appeared in the same edition. It shows the five core PAD leaders in front of the entrance to the dark cave of “politics of the parliamentary system,” with all sorts of dark creatures-the “evil politicians” — awaiting the pure newcomers. Sondhi holds the famous “candle of righteousness” to lead their way. The text in the right-hand corner below says, “A small candle in the darkest of caves.” Beneath the cartoon is a column by Chai-anan Samudavanija, one of PAD’s ideologues (who had been skeptical of the party idea), headlined, “The PAD party.”

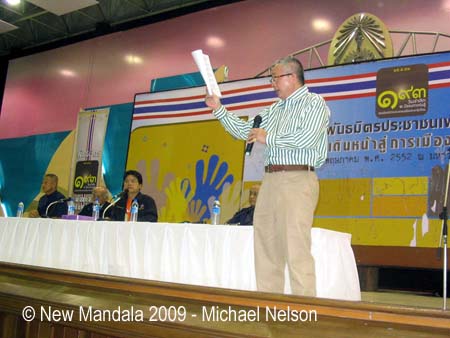

Sondhi Limthongkul during his speech, reading from the booklet mentioned above. To his left are the other four core leaders of the PAD.

Somkiat Phongpaiboon – still a party-list MP of the Democrat Party.

Phiphob Thongchai

Chamlong Srimuang

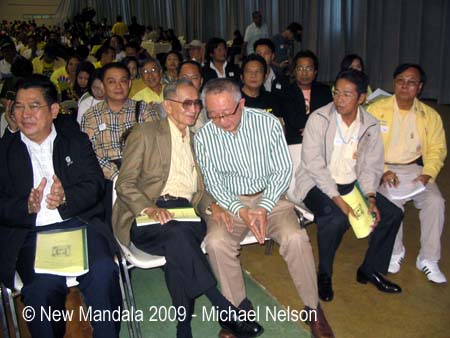

Prasong Sunsiri, the hard-line chairperson of the coup-installed Constitution Drafting Committee, talking with Sondhi. Prasong already had attended one of the very first events of Sondhi’s pre-PAD protests at Lumpini Park. Note his gesture of affection towards Sondhi (left hand on right knee). Prasong also gave a speech that was met with big applause by the audience. To their right is Praphan Khunmee, still an advisor to Democrat Minister of Science Kanlaya Sophonpanich. He has written a book titled, “I want my life to be the leg of the king and the slave of the people.” In the upper left-hand corner of the title page of his book is a big hand clapper — a key symbol of the PAD. To Praphan’s right is Phatcharakriengchai Singhanat, two-time constituency MP candidate for the Democrat Party in Chachoengsao province.

The meeting of Sondhi with Prasong prompted photographers to rush to the scene.

Part of the audience

The right sign says “phak isan” (Northeastern region), the left one welcomes “our political party.”

“Who harms the country? Who uses violence? Who assassinates Sondhi?”

“The future of the nation depends on every one of us.”

The boxes for the return of the questionnaires.

Waiting in line for lunch. The text says, “Fighting 193 days for new politics that is transparent — for Nation, Religion, Monarchy.”

Having lunch

Members of Santi Asoke served khanom chin and kaeng khiew wan with a smile. Some people who passed me while I was sitting in the grass under a tree eating from my bowl turned towards me, smiled and asked “phet mai,” on which I responded with “phet nit noi” (in fact, the meal was quite nice).

On 25 May, tens of thousands of PAD supporters assembled in the sports stadium of Thammasat University’s Rangsit campus (I did not attend this event, but other New Mandala coverage is available here). On the following day, the front page of ASTV Phuchatkan was appropriately exuberant screaming, “Overwhelming decision to establish a party!” On the bottom (left-hand side), we read, “25-5-52 a historic day,” while the text on the right-hand side reads, “The PAD raises the curtain of new politics.”

That the PAD sets up its own political party is a very interesting political experiment. Hopefully, the PAD party will have sufficient time for preparations before the next general election will take place.

Postscript

In a funny coincidence, political forces in the United Kingdom have also called for “new politics.” Combining demands of the PAD and the UDD, conservative opposition leader David Cameron said, “The central objective of the new politics we need should be a massive, sweeping, radical redistribution of power: from the state to the citizens; from the government to parliament … from judges to the people; from bureaucracy to democracy” (Bangkok Post, 27 May 2009). Two important issues concern replacing the first-past-the-post election system with a proportional system (this has also been floated in Thailand, though with little resonance), and the introduction of a fixed term for parliament (at present, the prime minister can call elections anytime within a five-year period).

Michael H. Nelson is a visiting scholar at the Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. Email: [email protected].

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss