In Papua, where state sovereignty and legitimacy is deeply contested, representation matters. So in this national election, who purports to represent Papua?

Candidate residence is one way of sizing up the candidates and the results are telling. 63 out of 114 candidates running for DPR (national house of representatives) seats in Papua province live within the greater Jakarta area. In neighboring Papua Barat, 17 out of 36 candidates live in greater Jakarta.

So, out of a total of 150 DPR candidates seeking to represent these provinces in 2014, only half, 53% to be precise, actually live in Papua.

Bad sign.

A quick review of CVs indicates that some of these Jakarta residents are ethnic Papuans, and many of them have extensive experience in Tanah Papua.

But a few of these Jakarta-based candidates have never actually lived here. If elected, their ability to adequately represent a constituency that voted for them is open to question.

Representation of residents versus non-residents in Papua province by political party also reveals some surprising results.

The new parties and the ‘presidential’ parties seem to have been particularly successful at attracting candidates who actually reside in the province. Meanwhile, the older, more established parties, who presumably have stronger party machines, continue to stock their candidate lists with non-residents.

Most Golkar candidates are non residents. However, this unlikely couple of candidates are not: Ex-regime militia head Yorry Raweyai, formerly of Pemuda Pancasila, and the son of murdered pro-independence activist, Theys Eluay, together in a Golkar campaign poster. Photo by author.

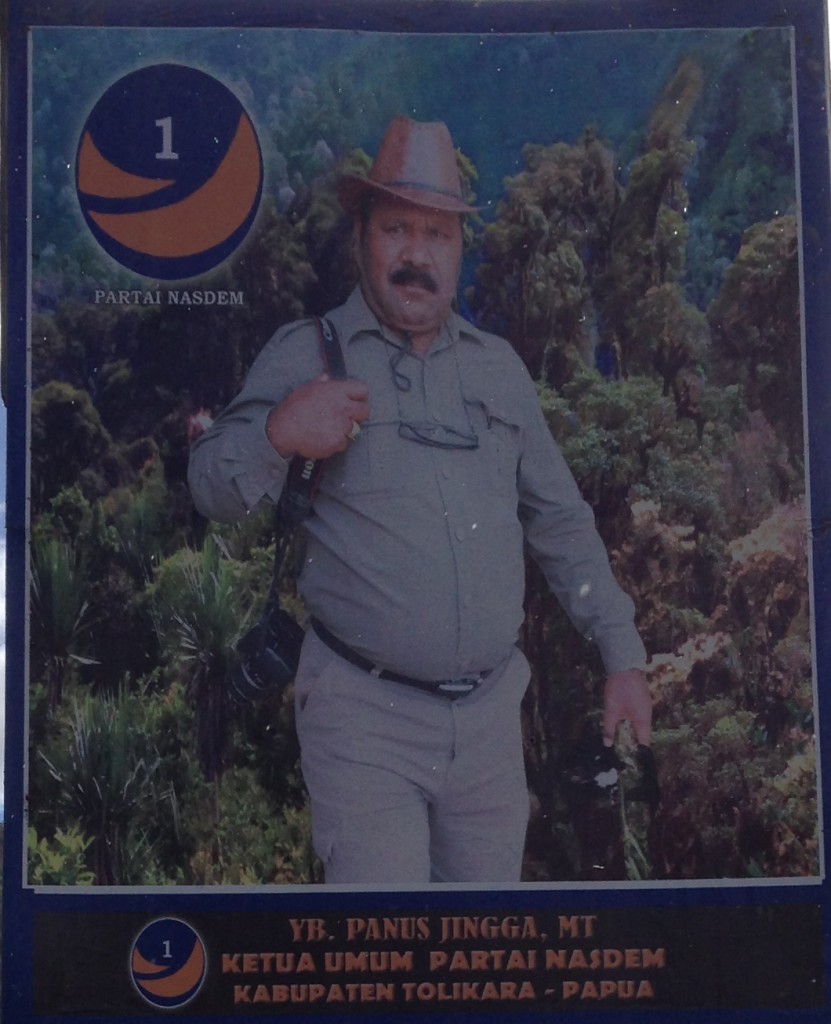

For example, Surya Paloh’s National Democrat Party or Nasdem, and retired general Sutiyoso’s Justice and Unity Party or PKP, have the greatest number of locals, with 8 out of 10 resident candidates each. They are closely followed by Prabowo Subianto’s Gerindra and SBY’s ailing Democrat Party; both have 7 out of 10.

On the other side of this coin rolls Megawati’s PDI-P, with 4 of 10, and the reheated New Order leftover Golkar, with 3 out of 10.

PDI-P is hobbled by Papuan memories of Megawati’s enthusiastic undoing of Papuan special autonomy, but this is more than made up for by Jakarta governor and front-running presidential candidate Jokowi’s star power. He is the only candidate that Papuans are enthusiastic about. Golkar remains the party of connections and contractors, and so will always have a stalwart base that will pause between the kickbacks long enough to vote.

Islamic parties fare on a scale of reasonable to poor. Nahdlatul Ulama’s PKB, has 6 of 10; Muhammadiyah’s PAN, 4 of 10, and PBB, 4 of 10.

The Orthodox Muslim party PKS, colloquially referred to as the beef corruption party [Partai Korupsi Sapi – PKS – geddit?] after a recent bout of corruption scandals comes in at a woeful 1 out of 5.

The real surprise here is the geriatric Partai Persatuan Pembangunan or PPP. Six of their 9 candidates actually live in Papua.

Still, let’s not get too positive about these 63 candidate-residents. 46 of them, or 73%, live in Jayapura city or Jayapura district.

Younger parties like Nasdem have successfully attracted a host of Papuan residents as party candidates. Photo by author.

But enough about address, what about actual hands on experience? Which parties have attracted candidates with some real political credentials?

Again, it’s the younger “presidential” parties that have attracted most of the experienced past administrators. Ex-Governor Barnabas Suebu and ex-Vice Governor Alex Hasegem are with Nasdem, while ex-Governor Freddy Numberi and pastor/ lecturer Noakh Nawipa joined Gerindra. Hanura’s Menase Robert Kambu wasn’t the best mayor of Jayapura, but he excelled where his passion lay- as Dewan Pembina [board of patrons] of the Persipura football club.

But too many other candidates are ‘fillers’, lacking any substantive experience either in Papua or as Papuans. For example, Partai Demokrat is fielding a candidate from Toraja that appears to have no link to Papua at all. One of Nasdem’s candidates is a Jakarta resident who worked in a travel agency, before joining the political fray.

Dividing the candidates up by ethnicity and religion is a particularly important way of grasping of representation for Papua. In a time of unregulated migration, Papuans legitimately feel subsumed by outsiders. Questions about “Papuan identity” is a significant dimension of the ongoing conflict between Papua and the national level government and that “identity” is measured in ethnicity and religion.

So contentious is the issue that Papua’s Special Autonomy law mandates that gubernatorial, vice-gubernatorial, and Bupati (district head) candidates must be ethnic Papuans.

The law resolves the fluidity and complexity of Papuan identity in narrow terms. Those born of a Papuan father and a non-Papuan mother are Papuan, those born of a Papuan mother and a non-Papuan father are not– go figure.

That said, this law does not regulate legislative candidates.

Below is a table of Papua and Papua Barat legislative candidates by ethnicity and religion.

| Candidate | No. of Candidates | Percentage |

| Papuan candidates | 80 | 53% |

| Non-Papuan candidates | 70 | 47% |

| Papuan & non-Papuan Christian candidates | 92 | 61% |

| Papuan & non-Papuan Muslim candidates | 56 | 37% |

| Papuan Muslim candidates | 24 | 30% |

| Papuan Christian candidates | 56 | 70% |

| Non-Papuan Muslim candidates | 32 | 46% |

| Non-Papuan Christian candidates | 36 | 51% |

*Percentages do not tally evenly in non-Papuan religions: I excluded non-Muslim/ non-Christians from the count.

The pluralist parties field a majority of Christian candidates, including Demokrat, Gerindra, Golkar, and Nasdem. Islamic parties like PKS field exclusively Muslim candidates, as do the other parties with a core Muslim constituency, to PPP, PAN and PBB. These parties tend to court the migrant vote. If the religious and ethnic identity of the candidates is anything to go by, the parties consider that vote to be of serious political importance.

Unsurprisingly, the Papuans I know aren’t enthusiastic about their choices. In the recent gubernatorial elections, my highland friends voted in new candidate Lukas Enembe in January 2013 but with no expectation of change. “I’m fine with whoever” remains a common sentiment among under-30s. This casual apathy stands in stark contrast to the recent regional elections in Aceh, Indonesia’s other province with a long history of armed conflict with the central government. There, voters were more cynical: Partai Aceh intimated a return to war if they lost, and my friends there voted for that gaggle of louts, not to govern, but to behave.

In Aceh, voters were intimidated; in Papua’s highlands, they were created. The Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC) report “Carving up Papua” described how the 2012 provincial voter’s list (KPUD) contained 2.7 million names, which was almost equal to the entire provincial population according to the 2010 census. 65% of 2013 gubernatorial votes came from the highlands, which in 2010 contained 50% of the population. In highland Yahukimo, the KPUD numbers were 157% of the 2010 numbers. In Intan Jaya, 152%; in Tolikara, 151%; in Yalimo, 132%; in Puncak, 126%. In Enembe’s home district, Puncak Jaya, where he was Bupati for two terms, it was 151%, with 99.5% of votes going to Enembe.

One wonders how these non-existent voters will cast their ballots, especially in the highlands.

Special thanks to my friend Justin Snyder, who offered me a few choice morsels from his extensive mining of the KPU website.

Bobby Anderson works on development issues in Eastern Indonesia, and he works and travels frequently in Papua and Papua Barat. This and other writings can be found at http://independent.academia.edu/BobbyAnderson

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss