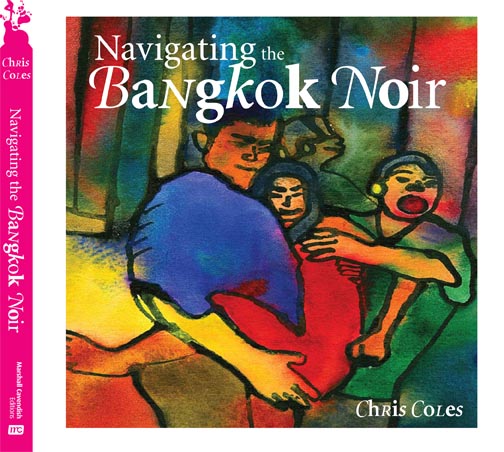

[There will be an Art Opening/Book Launch event for Navigating the Bangkok Noir at Koi Gallery, 43/12 Sukhumvit Soi 31, Bangkok, at 7 PM, Friday 1 April 2011].

Bangkok at midnight: streets splashed with neon, tourists feeding bamboo to baby elephants, hookers eating at roadside tables, eyeing those who pass by, and soldiers in combat kit, carrying automatic weapons standing on the BTS, watching, waiting, taking in the sights. If noir had a smell it would be jasmine on a hot tropical night in Bangkok, the City of Angels. It is a beat that I’ve covered for more than twenty years. The thing with black is even when you scratch the surface, you can never find your mark. It vanishes like dreams, hope and love.

Chris Coles likes to say there is a noir movement in Bangkok. The quantum world has a lesson: we must choose between measuring position and velocity of particle. Noir, for me, moves so fast, I can never nail down exactly where it is, where it has been or where it is going. It is a particle in motion smashing through the walls, consciousness and lives of people living in the City of Angels.

Every artistic movement is created by a group of writers, painters, photographers, filmmakers, and lyricists. While they mostly work in isolation from each other, they draw from the same material, and their creativity combines into a larger force than any one of them. In the case of the Bangkok Noir movement, the idea of a noir community started to take shape as these artistic individuals began to assemble in ever larger numbers about ten years ago. A number of factors, social and political, have come together to form a critical mass, allowing for the noir movement to not only take hold but to gain international attention. Mass media and mass tourism has helped to make the developmental changes into the kind of perfect storm that feeds the instability and insecurity that creates noir.

I think of Chris Coles as occupying Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s shoes in Bangkok. For my money, Coles has grabbed from the nightlife hundreds of images, vested them with vibrant, gaudy colors, his theatrical images of faces smeared with regret, hope, boredom and hate. He catches his subjects in the throes of navigating the night world heavily mined with pleasure, power and money explosives.

Toulouse-Lautrec captured Montmartre nightlife. A century later, Coles has found his Montmartre in Soi Cowboy, Nana Plaza and Patpong. Coles’s passion has been a large-scale work in progress to translate the bohemian Bangkok lifestyle into art. On the surface, the paintings are about world of sensual pleasure where romance is manufactured in these dream factories. Noir is hidden below the surface of these places of work. Go behind stage and you find what you’ve long suspected, work is about putting in time for money and workers value themselves according to the money they earn. Like Toulouse-Lautrec, Coles’ figures are objects of compassion and sympathy. We know that both sides of these transactional arrangements are doomed. There is no need to leer or show disrespect as the reality that the darkness of such lives fills us with a deeper knowledge of hopelessness. In painting after painting, Coles reveals bar girl and customers mental processes. The ones they carefully hide behind a smile.

What makes Chris Coles noir vision unique is his skill to draw powerful psychological images from inside the world of Bangkok’s entertainment industry. His haunting faces and scenes emerge from the darkest corners of humanity; the gangster, the prostitute, the dispossessed, the traveler, the nice guy freshly arrived on holiday, the people on the run–from themselves, their family, country–all of these souls are stirred in the cauldron of Coles’ imagination. He mingles his colors with shades of innocence and hope but we know from their expressions and stories that disaster is a couple of minutes away.

His subjects are caught in a bubble of wonder and sensitivity, unaware that like a condemned man, they have no idea they have mistaken the executioner’s smile as an invitation to pleasure. I reminded of the first time years ago (1993), when I walked through Tuol Sleng, or Security Prison 21, a museum to the Khmer Rouge victims. The faces of men and women in the photographs on the walls were frozen in a moment of horror, the self-realization of what was coming next. Coles’ Bangkok subjects are emotional kin who share the same look of incomprehension, pleading, and worry.

Capturing the pathos of the Bangkok night is the goal of noir creators. But this is no easy thing. What Chris Coles brings to the table is of extra value: he delivers a hard driving narrative description of the setting and characters, which accompany each painting. The effect is to create an illustrated short story as a time capsule stuffed with images and stories that magnify the haunting illusion of reinvention through carnal pleasure. In painting after painting, Coles shows us men–mainly but not exclusively foreigners–and Thai women–mainly though not exclusively prostitutes. A rap sheet with Tuol Sleng mug shots of people shedding one set of dreams for another, their emotions and lives riding on the conveyor belt that morphs into a roller coaster slamming a hundred miles an hour world through the Bangkok night.

Coles guides us through his images and accompanying short vignettes, to witness a strange ballet of men and women whose emotions are filtered and shaped by cultural misunderstanding, language incompatibility, and moral and ethical mismatches until all that remain are residue of mental projections–one person’s vision and wishes as to what the other person is and wants.

In this book, modern pop art merges with contemporary pulp story telling. The individual narratives reinforced and enlarge our understanding of the paintings. The language is expat English, funny, dead pan, screaming at the top of one’s lungs prose like a machine gun cutting down a frontal assault. Each story attached to the painting establishes the context and perspective for what you are seeing. In the past, for many years, Chris Coles was involved in making films. In this collection, he has story boarded the world of the Bangkok Night from the inside. He portrays his subjects anxiety, desires, dreams, and delusions, and perhaps, above all their vulnerability where survival depends on the skill to exploit the weak, the romantic, and inexperienced.

Noir is more than paintings laced with plumes of cigarette smoke, bottles of beer, angry tarts, and dissolute drunks, it is a world of broken dreams, shattered lives, exploitation–that word born of noir–and thirty word English vocabularies that must carry the full weight of pleasure and desire, and the rundown short time hotels. This is the opposite of the fairy tale where the orphaned girl is swept up by a prince and given a glamorous life. Noir is the spotlight held on people caught without escape from a pleasure-domed hell. The Bangkok nightlife is where money is the only vocabulary worth memorizing, the only way of measuring happiness and success. And dreams of a better world have a long passed their expiration date.

Most of the Thai women in the Bangkok bars have traditionally come from the Isan, the poorest region of Thailand. We find out about the background of these women–largely peasant girls born and bred in small villages, daughters of rice farmers, women who have had little chance of a acquiring a formal education. These women have seen other girls return from Bangkok with a foreign boyfriend or husband. Often the returning woman comes back as a heroine to her classmates, who admire her iPhone, expensive clothes, handbag, watch, and fistful of money to buy food and drink for all. Thus starts a fresh cycle of new faces appearing in the clubs, bars, and restaurants inside Bangkok’s scattered nightlife. Those women who have stayed behind and married local boys, have their children but little else. It’s not uncommon for them to have been abandoned by their husbands without any financial support. Next thing they are on a bus to Bangkok, children left with the grandmother or aunt, with a promise of money to be sent back. Soon she is dancing naked and sleeping with foreigners, and perhaps taking drugs to numb the pain of separation from her children and the disgrace of what she is doing.

Coles digs deep to tell their stories with compassion and introspection. He goes inside their lives and we come away with a greater understanding of what forces unite a bar girl from a poor region in Thailand to a foreigner who knows little of her culture and language inside a Bangkok bar. But this happens every night of every day of every week of every month and year. A relentless, pounding, unstoppable dance between men with money and power and women who understand that sex is the easiest short cut for someone with no other marketable skills or education. Sex in the noir world is a system that redistributes money and power to women. It’s not about reproduction or a relationship or marriage, though these may, now and again, happen as a freakish by-product.

In these paintings, Coles has captured the contradiction of Bangkok, the noir part, where at the moment of greatest relaxation is the moment when one should be the most vigilant. The void is always waiting between the laughter and smiles, to swallow up the outsider, consume him, hold him, digest him and wake up the following day hungry for a new meal.

[This article was written by Christopher G. Moore as an Introduction to Navigating the Bangkok Noir. For some more information on Moore and Bangkok Noir see here and here.]

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss