This post is part of New Mandala’s month-long feature on Thailand’s constitution referendum. The referendum was held on 19 August 2007.

Compared to the weeks immediately before the voting in elections or, in this case, the referendum, polling day usually is a rather boring affair. It mainly concerns the processes in polling stations, which may be located in schools, tents (Image 1), temples, or other public places. This referendum was also rather boring for the polling station committees, simply because voter turnout in Chachoengsao dropped from 76.36% in the 2005 election to a mere 57.07% in the referendum–notwithstanding all the state’s concerted efforts to mobilize voters by all sort of means. While there were often long queues during the entire period of voting in 2005, people rather more trickled to the polling stations this time around (see Image 2).

Image 1

Image 2

Below is the obligatory picture showing a voter putting his ballot into the ballot box (Image 3).

Image 3

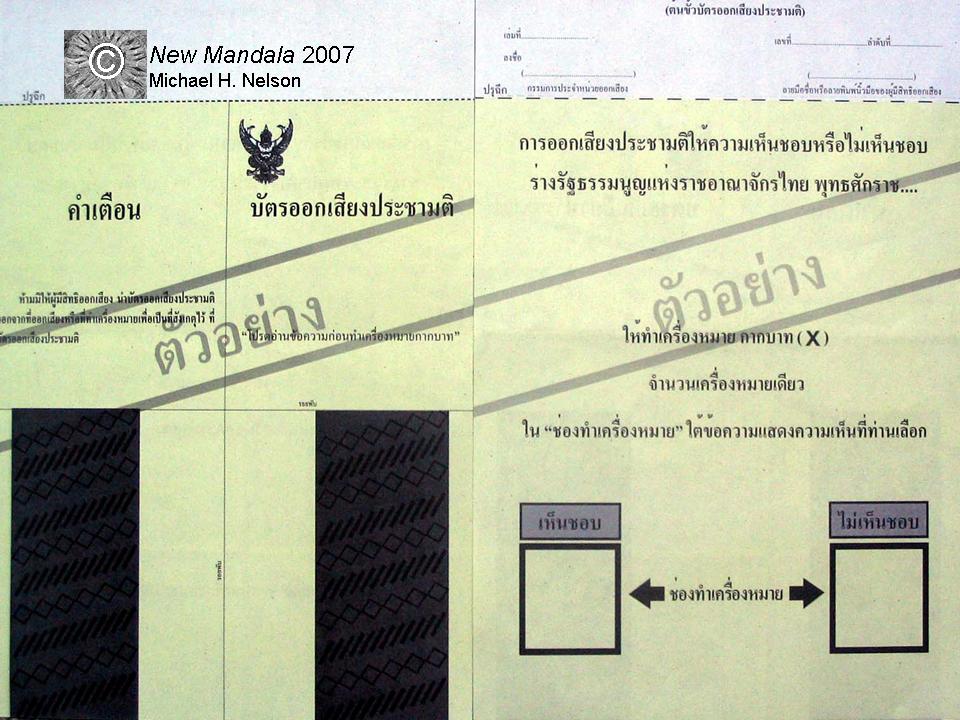

The ballot itself was much smaller than usual, because there were only two boxes–“hen chob” (accept) and “mai hen chob” (reject). In fact, people did not have to answer a question, but rather react on a statement, namely “Voting in the referendum to accept or reject the draft constitution of B.E….” (Image 4).

Image 4

Besides the 819 ordinary, community-based polling stations, there were also four polling stations for voters who had registered with the office of the provincial election commission to cast their votes in Chachoengsao, although their residences were registered in another province. In 2001 and 2005, 229,709 and 348,739, respectively, registered, while only 275,692 and 143,153 people actually turned their registration into a vote. For the referendum, only 3,050 voters registered, and only 1,407 of them actually turned up at the nok khet changwat polling stations (see Image 5). Of them, 946 voted hen chob, 450 mai hen chob, and 11 ballots were invalid.

Image 5

Immediately after the polling stations closed at 16:00, counting started. I observed this exercise in two adjacent tent-based stations on the left and right hand sides of what used to be a small market in the Chachoengsao municipality (talat kueakun). I arrived just in time on a motorcycle taxi from the nok khet changwat polling stations. As usual, one person would take a ballot at a time out of the box, unfold it, and hand it over to the second official. He would hold up the ballot for observers to see and clearly and loudly announce were the cross was made–“hen chob” – “mai hen chob” (Image 6). A third official would receive the ballot paper from the announcer, refold and perforate it to indicate that it had been counted. Meanwhile the fourth member of this team would have put the proper mark on a big counting sheet affixed to a counting board.

Image 6

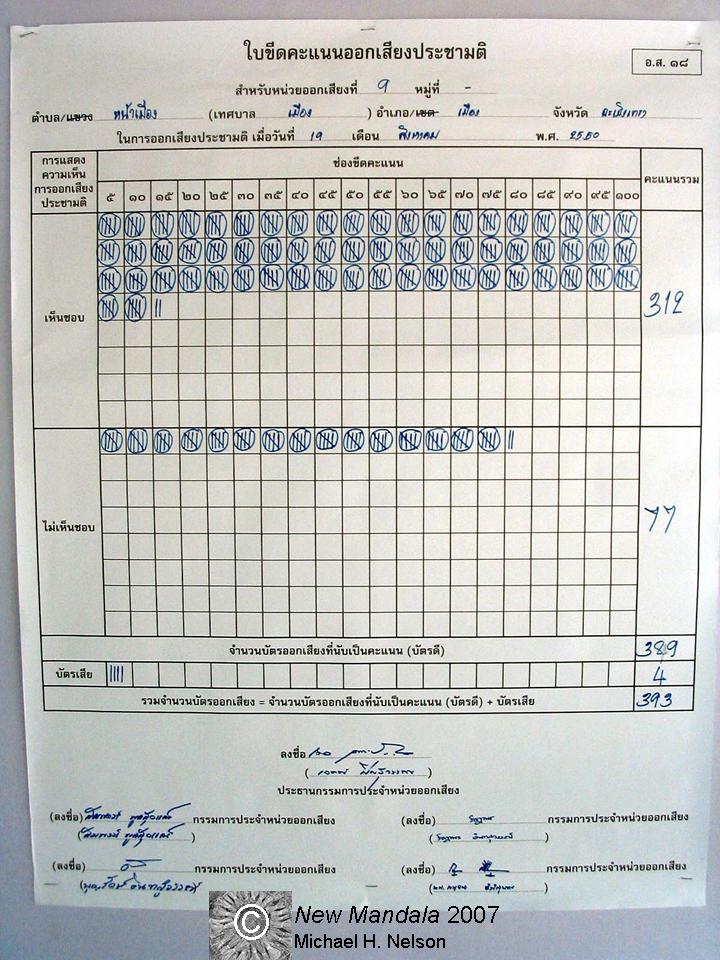

After a short period of counting, it became clear that the constitution–or whatever voters had on their minds when they made their decisions–had won a clear majority. A 16-years old boy who had participated in the Chaisaeng’s “we vote no” march the day before came to me saying, “Lung (uncle), our march does not seem to have had much of an effect.” Indeed, the result of the counting was clear, as is shown in Image 7. After polling station committees had finished their job, they returned their electoral utensils to the meeting room of the Amphoe Mueang district office (Image 8).

Image 7

Image 8

The local stringers of national media hung around the office of the Provincial Election Commission for some time, until they could get the results (see Image 9). On Monday, which the government had declared a special public holiday, a big signboard with the results was erected in front of the old provincial hall (Image 10). Finally, on Tuesday, the provincial election commissioners were also formally informed about the national and local results of the referendum by an official from their office.

Image 9

Image 10

Image 11

As for Chachoengsao, it is noteworthy that voters in Sanam Chai Khet district contradicted the trend in the province by producing a slight majority for rejecting the charter. Thatakiap district had a relatively narrow majority for acceptance. Both areas belong to the political sphere of influence of former TRT MP–now disqualified–Suchart Tancharoen. In the ill-fated 2006 election, he was the only one of Chachoengsao’s four TRT MPs who received greatly more votes than “no votes” and invalid ballots combined. All of his three fellow MPs were defeated by those who abstained or invalidated their ballot papers. Reportedly, Suchart plans to field an elder brother in the election. Since his father–whose barami (“charisma”) was the source of Suchart’s strong voter base–died last year, it remains to be seen whether this will have an impact on his electoral prospects.

The Chaisaengs did not only lose in the election of April 2006, but also publicly placed themselves in the camp of die-hard loyalists of Thaksin, now assembled in the People’s Power Party, during the referendum period–and lost again. One wonders whether voters will keep both events in mind and thereby open up the possibility of better election results for the candidates of the Democrat Party. However, these candidates would have to depend on voters’ preferences for the Democrats, because they themselves are unattractive. Electoral prospects will probably also depend on what sort of winning coalition options might occur in the run-up to the elections. The Chaisaeng situation certainly is much different from the time of the 2005 elections, in which they substantially benefited from Thaksin’s overwhelming popularity. Their campaign would not become any easier if a relatively clear anti-(former)TRT coalition, including the Democrat Party, formed ahead of the elections. The fourth MP had his origin in the Chart Pattana Party; he might thus return to follow Suwat Liptapanlop, who has steered a low-key middle path after the coup.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss