The conviction, on July 26, of Kang Guek Eav–“Duch”– former prison chief of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia, drew international media attention to Cambodia, at least for one news cycle. The verdict of the UN- sponsored tribunal, was important in that, for the first time, a key Khmer Rouge official was held accountable for the unspeakable crimes of the regime. The press highlighted the outcry that the sentence, 19 years in jail, was too lenient.

International coverage of the Duch verdict eclipses two issues. First, the international community is ambivalent about the tribunal. Many consider it deeply flawed by corruption and interference by the Cambodian government. Others, especially in the West, insist that the tribunal must continue, as if this were the only road to justice and reconciliation in post-Khmer Rouge Cambodia. Nothing is farther from the truth.

Given the trial’s thirty-year delay, Cambodia has since returned to stability and won the confidence of both donor and business communities., Cambodia’s growth rate over ten years stands at 7 – 13%. This is the result of a rise in tourism and private investment, but also of the generous inflow of foreign aid, since 1993, when a new Cambodian government was formed after UN-sponsored elections. Given the Cambodia’s expanding population pyramid, today, a majority know very little about and have no experience of the Khmer Rouge era. Recent surveys indicate in fact that Cambodians are paying little attention to the tribunal. The youth of Cambodia, like their peers in Hong Kong, Shanghai and elsewhere are more focused on building the future.

A less evident problem is that the past role of international actors in the Cambodian tragedy has been whitewashed. Almost in unison, they now assert that the Vietnamese liberation of Cambodia from Khmer Rouge rule, in January 1979, was followed by “ ten years of civil war”. What they fail to report is that this civil war was largely brought on by what happened in faraway New York, where, incredibly enough, spearheaded by the US and China, the United Nations continued to recognize the ousted Khmer Rouge as the legitimate government of Cambodia, rather than the new People’s Republic of Kampuchea, which soon gained control over 90% of the country. The alleged reason was that Vietnam had invaded Cambodia, but the obvious truth was that Vietnam was on the wrong side.

Opposing this UN decision to maintain Khmer Rouge representation were the Soviet bloc, India and a number of others, who were easily outvoted. This stalemate continued for 11 years during which the Khmer Rouge flag continued to fly over Manhattan. To disguise this outrage, the Khmer Rouge was draped in sheep’s clothing, as a “Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK)”, with two non-communist factions–the Royalist FUNCINPEC and a pro-American group, the KPNLF. In the field, this CGDK received ample aid from its Western backers, fueling and prolonging the “civil war” referred to by the international press today. With the end of the Cold War, in 1991, the Paris Peace Agreements were signed, and the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia brought the stalemate to an end by organizing elections that established a new legitimate coalition government in Cambodia.

Having succeeded in seating the Khmer Rouge in the UN General Assembly for eleven more years, obviously the West was not in a big hurry to put the Khmer Rouge on trial. It is ironical that the international press and Western academics, almost in unison, now insist that the K.R. trials must continue, and that the Cambodian government should not protect anyone from the tribunal.

If the international tribunal were to end tomorrow, Cambodia would continue on its path to progress and reconciliation, aided by private investment and generous donors, whose efforts continue to lift Cambodia from poverty. This, understandably, is the subject that concerns Cambodians today.

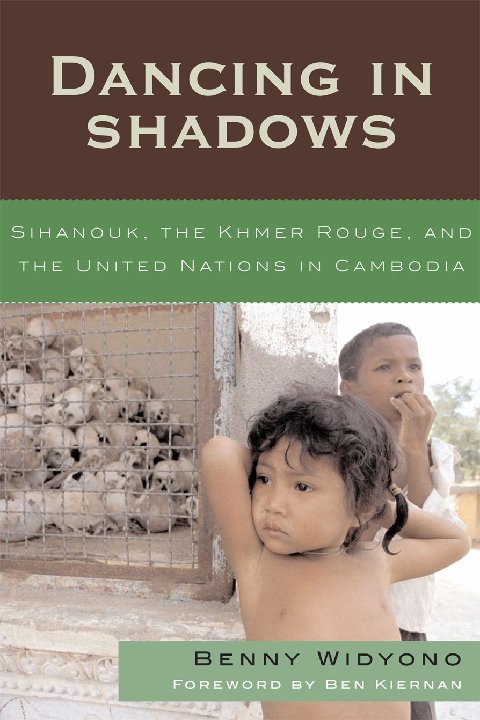

Ambassador Benny Widyono, from Indonesia, was Governor of Siem Reap Province under the United Nations Transitional Authority, 1992-1993, and the Secretary-General’s Representative to Cambodia 1994-97. He is the author of Dancing in Shadows: Sihanouk, the Khmer Rouge and the United Nations, Rowman Littlefield, Lanham: 2008.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss