Ovesen, Jan (1993). Anthropological Reconnaissance in Central Laos: A Survey of Local Communities in a Hydropower Project Area. Uppsala Research Reports in Cultural Anthropology. No. 13. Stockholm: Department of Cultural Anthropology, Uppsala University.

In the annals of anthropologists working in the Lao development industry, Jan Ovesen’s 1993 study of local communities along the Theun, Hinboun and Gnouang Rivers must be amongst the earliest. Ovesen’s study represented a consultancy, which formed part of the feasibility study for the Theun-Hinboun Hydropower Project (THHP)– amongst the first dam projects in Laos constructed under the Independent Power Producer model. While there are a number of useful ethnographic observations made the study, ultimately I forward that the report is perhaps more valuable as an example of ‘applied anthropology gone astray.’

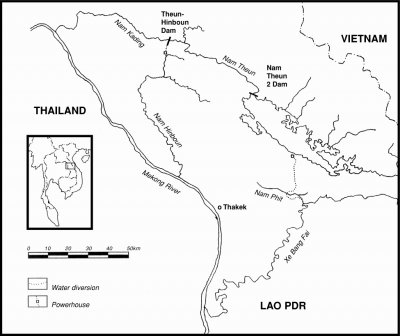

Ovesen’s study was conducted during the initial planning stages of a series of major development interventions on the Nam Theun-Kadding and Nam Hinboun watersheds in central Laos, which include the Theun-Hinboun Hydropower Project, the Nam Theun 2 project and the recently completed Theun-Hinboun Expansion Project. In this and the next two New Mandala postings, I will explore in more detail how these projects have produced significant socio-ecological changes along the Hinboun River, and how ‘ecological knowledge’ has been produced and applied (or not) in the process.

Ovesen arrived in Laos with two objectives for his study: i) a determination of the cultural groups present in the area of the then proposed Theun-Hinboun hydropower project, ii) an evaluation of whether any of the local groups present in the project area may be disadvantaged by the development and operation of the project.

Theun-Hinboun Watershed (Souce: International Rivers)

First, I note the positive aspects of the study. Ovesen makes a series of interesting ethnographic observations regarding the local communities he visited along the Nam Ngouang, Nam Theun and Nam Hai. His informants reported that on the Nam Hai, crop losses due to flooding might occur every 8 to 10 years, a situation attributed to backwater effects from the main Mekong channel. Lower down the Nam Hinboun, Gordon Claridge (1996) reported that rice paddy crops would be flooded for short periods of time each year, with paddy lost to prolonged flooding in one out of every 4 years. Ovesen’s observations on the agricultural practices of local residents are useful–for example how riverside farmers might continue with conducting upland swidden agriculture even though the opportunities existed for moving into wet rice production (e.g. ownership of buffalo, potentially suitable terrain). Ovesen writes:

…the reality is that competence in paddy cultivation is not something people are born with. In the upper Nam Hai plain, at least, most of the inhabitants are relative newcomers from the Nam Theun area, where paddy cultivation was never part of their traditional cultural knowledge. (p. 21)

This fits with my research experiences lower down the Hinboun, where villagers reported only moving into wet rice in the 1960s, and only after a couple of farmers from Northeast Thailand and southern Laos, with knowledge of wet rice cultivation, married into the village. Ovesen also reported on a hybrid form of wet- rice/ swidden cultivation on the Nam Hai, whereby farmers planted bunded lowland paddy for up to 5 years and then left the fields to fallow for a couple years. “Wet rice” and “swidden” are two ends of a spectrum of agricultural technology, with a range of farmer practices, in places such as the Ngouang-Theun-Hai-Hinboun watersheds, falling in between these poles.

Ovesen’s observations concerning the importance of fishing are of general interest (reported as very important on the Nam Theun and Nam Gnouang, moderately important on the Hinboun and less so on the Nam Hai). And he argues that the importance of forests for village livelihoods can “hardly be overstated” (p. 30). His notes on the ethnic origins of the Lao Kaleung and Tai Khang people of this area of Laos is also of interest– for the Tai Khang, arriving from Vietnam through Sam Neua and Xieng Khouang, with a cultural heartland in Ban Phontan, in present day Bolikhamxai province (p. 26-27).

Unfortunately, Ovesen’s study goes off the rails when it comes to an understanding of upland ecology and hydropower interventions. I suggest that the problems are linked to three key biases: a) Ovesen’s presumption of a pre-existing socio-ecological crisis of swidden agriculture in the Nam Gnouang/Nam Theun, which is inferred, not demonstrated through evidence; b) an assumption that hydropower development interventions would then effectively help to ameliorate or redress this crisis; c) a lack of attention to the likelihood of new social and ecological externalities created by hydropower development, particularly for downstream areas along the recipient river (the Nam Hai- Hinboun). These biases lead the author into an overly favourable judgment of the Theun-Hinboun inter-basin diversion project, and indeed into making sweeping recommendations for large-scale population resettlement.

Based upon 17 days of local fieldwork, on his third visit to Laos and his first trip to the project area, Ovesen arrives at the conclusion that there a severe ecological crisis was in play on the Nam Theun-Nam Gnouang area, and given this purported crisis, that “…positive measures be taken in connection with the project to induce the greater part of the population of the Nam Theun/Nam Gnouang area to move into the Nam Hai area and take up paddy cultivation” (p. 24). He bases his notion of an ecological crisis upon four points:

- a reported 8 year swidden fallow period in the local villages he visited

- a reported separation of 6 km of villages from some of their upland rice fields

- a reported high rate of population increase

- and the broad notion that swidden would produce on average less rice per hectare than bunded wet rice paddy

There are significant and I would argue quite unwarranted assumptions at work here, which disregards alternate options for improving village livelihoods and the sustainability of the swidden/wet rice/fishing/forest livelihood system without resettlement programmes or the development of the Theun-Hinboun inter-basin hydropower scheme.

Based upon these insights, Ovesen then recommends that local people from the Nam Theun and Nam Gnouang be persuaded to move to another watershed, the Nam Hai plain, through the provision of

- free transportation of disassembled houses and belongings

- appointment of agricultural advisors

- supply of electricity along the Nam Hai

- electrical pumps and pipes for irrigation of the paddy fields

We will revisit these ideas of establishing dry season irrigation in project mitigation and compensation initiatives in my next two postings.

The study concludes with a rather glowing endorsement of the proposed Theun-Hinboun hydropower project. Ovesen writes:

I have been unable to detect any ways in which the project could in the long run adversely affect any of the population groups in the area…The import of such elements will inevitably affect the ‘traditional’ culture of the local population in various ways, but this is not necessarily a bad thing, or something that should be avoided at all costs…. If the aforementioned recommendations are followed, it is my considered opinion, supported by the results of the study, that the project, from an anthropological point of view, may only have positive (direct and indirect) effects on the society and culture of the local population. (p. 73)

Ovesen indicated his hope that the implementation of the Nam Theun ┬╜ project (as the Theun-Hinboun project was known at the time) would mean the cancellation of the Nam Theun 2 project. This did not come to pass. Not only were the Theun-Hinboun (start up in 1998) and Nam Theun 2 (2010) projects both constructed, but the Theun-Hinboun Expansion project (constructed to compensate for the river drawdown effects of NT2) then also flooded the Nam Gnouang valley in 2012,and doubled the inter-basin diversion of water from the Gnouang-Theun-Kidding system into the Hai-Hinboun system.

On the one hand, this report could be considered as an interesting if relatively minor footnote in the history of Lao hydropower development. As an example of applied anthropology, it strikes me as odd, to say the least, that an academic anthropologist with an admittedly limited understanding of local context, could be so willing to endorse such dramatic social and ecological engineering interventions. More seriously perhaps, this study arguably formed part of a discursive process that minimized (in the extreme) the probable ecological outcomes of a major inter-basin diversion hydropower project such as that of Theun-Hinboun Hydropower. The implicit assumption appeared to be that because no actual resettlement was entailed in the first THPC project, therefore there would be no significant social impacts. Because the state of ‘expert’ knowledge was so favourable, no baseline studies were conducted prior to the startup of THPC, and indeed the rhetoric of project supporters was that more water would produce more fish for downstream villagers (FIVAS, 1996).

Struggles over competing interpretations of the social-ecological effects and outcomes of the THPC project, and struggles over the production and legitimacy of ecological knowledge about this watershed, continued in the years after the Ovesen study (e.g. Shoemaker, 1998; IRN, 1999; Shoemaker, 2000). In my next posting, I will highlight a 2007 document, interpreting how the situation on the Nam Hai and Nam Hinboun had changed in the ten years since the start-up of the THPC project, prepared by a hydropower consultant insider ‘gone rogue’.

References

Claridge, Gordon (1996). An Inventory of Wetlands of the Lao PDR. Bangkok: IUCN.

International Rivers Network (1999). An Update on the Environmental and Socio-Economic Impacts of the Nam Theun-Hinboun Hydroelectric Dam and Water Diversion Project in Central Laos. 15-17 August 1999. www.irn.org .

FIVAS (1996). More water, more fish? http://www.fivas.org/sider/tekst.asp?side=107

Shoemaker, Bruce (2000). Theun-Hinboun Update: A Review of the Theun-Hinboun Power Company’s Mitigation and Compensation Program. December 2000.

Shoemaker, Bruce (1998). Trouble on the Theun-Hinboun. A Field Report on the Socio-Economic and Environmental Effects of the Nam Theun-Hinboun Hydropower Project in Laos. April, 1998. www.irn.org/programs/mekong/threport.html.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss