Michael K. Jerryson, Buddhist Fury: Religion and Violence in Southern Thailand

New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. Pp. 262; maps, tables, photographs, appendix, bibliography, index.

Reviewed by Tim Rackett.

Buddhist Fury explores the relationship between religion and violence in the far South of Thailand, where Buddhist monks are a marginalized local minority. Michael Jerryson focuses on the Buddhist and monk “side” of the Thai state’s conflict with Malay Muslims and thus explores a previously unexamined dimension of that conflict. His book is also a welcome corrective to the received wisdom in Thailand, which demonizes Islam as a violent religion causing conflict in the country’s far South. Building on the work of Mark J├╝rgensmeyer, Stanley Tambiah, Duncan McCargo and Brian Victoria, Jerryson debunks the myth of Buddhism as a moderate, moral spiritual force operating “above” the political and outside the state.

Whilst Buddhism is not violent in and of itself, as a lived tradition it can lend itself to dark and deadly uses. There are Buddhist dimensions to the Thai state’s violent struggle to control the country’s far South. To make sense of insurgent violence and the response to it, we have to understand the intricate interdependencies and interconnections among “race”, rule and religion in Thailand. To that end, Buddhist Fury examines “the role of Thai Buddhist monks in a religio-political conflict” (p. 5): the impact of violence on Buddhist monks and the ways in which, as actors in their own right, those monks have an effect on the ongoing violence. Its author asks whether the practices and habits of Buddhist monks in a violent environment exacerbate or ameliorate violence.

The performance of monasticism entails being a dhammic vessel, blessing people and amulets, purifying, offering merit on alms rounds, conducting rituals, living an ascetic lifestyle. Each of these roles and forms of agency is interrupted through and changed by violence. Being a Thai monk is not the same in all parts of the country. How to be a monk is prescribed by socio-political parameters and fantasy. Buddhist Fury demonstrates the ways in which religious identifications “interact with concepts of race, ethnicity and nationalism” (p. 185). Thus, whilst the cause of violence in Southern Thailand has ecological, economic, drug and political dimensions, for Jerryson, the “most pervasive, persistent and systematic problem is based on identity-formation” (p.183). Thai religious nationalism sets out the norm: to be Thai is to be Buddhist. This norm combines race and religion in a form of rule. Any solution to the conflict, argues Jerryson, requires making a space in Thainess for Malay-Muslim identity. It demands an inclusive “reworking of Thailand’s concept of racial formations”, which act to “displace minority identities by measuring their ethnic and religious identities against the norm of Thai Buddhism” (p.183).

Buddhist Fury is divided into five interrelated chapters, each examining Buddhist dimensions of violence in southern Thailand.

Chapter I provides historical context for the southern conflict. It addresses how and why a “master narrative” of Thai historical truth predominates in accounts of the region, justifying Thai Buddhist rule by excluding and delegitimizing Malay-Muslim claims to autonomy and ethno-religious identity. The political role and representations of southern Thai Buddhist monks in relation to the conflict are explored in Chapter II, “Representation”. How did Thai Buddhist monks come to be “walking embodiments of Thai nationalism”? (p. 50). What exactly do monks signify? Thai monks’ roles mean that they are agents of both state and sangha, representing the sacred and the profane, as living symbols of the dhamma and representatives of Thainess, of the Thai polity. It is monks’ political agency that explains their being targeted by insurgents. As representatives of the Thai state, monks are, unintentionally, a catalyst for escalating religious violence and identity politics. Jerryson argues that the conditions for evoking Buddhist violence are a space of conflict; politicized Buddhist images, roles and representations; and any defacing assault upon the sacred status and incarnation of those latter.

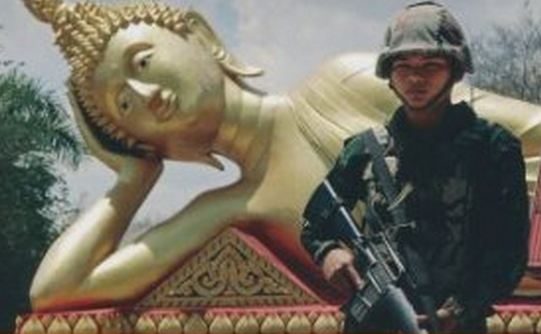

Chapter III, “Practice”, focuses on the ways in which being a Thai Buddhist is learnt and performed in a specific way in the southern Thai conflict zone. Using the personal narratives of southern monks, Jerryson shows how the role of Buddhist monk has been politicized as a response to violence and, furthermore, how it incites Thai religious nationalism. Monks incarnate and signify the legitimacy of the Thai state in a “convergence of Thai sacrality and governance” (p. 81). The theme of being a Buddhist and what this role entails is pursued in Chapter IV, “Militarization”. Mobilizing religion transforms security forces into “moral guardians, sacred avengers of the nation, not mere State servants, whose sacred duty is to uphold and protect the integrity of Thai Buddhism” (p. 75). The consequences of the defense of monks and local communities against insurgent attacks, as that defense is undertaken by Buddhist soldiers and police, are the militarization of Buddhist identities and spaces. Temples become fortresses and military camps. We have seen the advent of a seemingly enigmatic figure of the military monk, the “thahan phra”.

Jerryson’s most astute and perspicacious insights and interpretations–in Chapter V, “Identity”–concern the under-investigated notions of “race” in Thai identity, the phenomenon of state racism in Thailand and the relationship of those notions and that phenomenon to religion and violence. Jerryson shows that race and ethnicity are mobilized and combined with religion. Being Thai is a state-produced racialized identity, with its source in Siam’s response to Western colonization and Buddhist and Hindu religious traditions. Thai identity politics doubly excludes Malay Muslims from Thainess: for their other religion and for their racialized status as “khaek”.

The comparative and historical narrative in Buddhist Fury helps render the religious violence in southern Thailand intelligible as a norm and not an enigmatic exception. Buddhism, in thrall to Thai state nationalism, functions as a fundamental marker of ethnicity and imagined “race” to the end of domination and rule. In Jerryson’s analysis the political issue at stake in the far South of Thailand seems to be Malay Muslims’ desire “for autonomy based on ethno-religious identification” (p. 8) and the Thai state’s denial of their voice and of space for their socio-political aspirations and interests. This political drama is, however, reconceptualized through nationalist fantasy as an anti-Thai clash threatening to destroy Thai civilization and unleash anarchy. Buddhism is used to manage the “state of emergency” in the South.

Buddhist Fury concludes by suggesting ways in which ethno-religious conflict can be ameliorated by a different use of Buddhism. Rather than as an instrument of rule to handle a religious security threat, and thus as fuel for Buddhist nationalism and strife, it could be deployed in conflict resolution, fostering inter-faith communal bonds.

Jerryson’s iconoclastic analysis draws on interviews with thirty abbots, with monks and with soldiers. It is based on participant observation of different southern Thai Buddhist communities. It does not centre on Buddhist doctrine and texts but rather on “local situational performances” (pp. 17, 83) of being a Buddhist. Buddhism as a “lived tradition”, outside Western idealized “Platonic” representations, is diverse, fluid and contradictory. Buddhist truth and traditions are not universal and eternal but are rather enmeshed with particular interests and power relations.

How, then, is the non-violent image of Buddhism maintained? Such an image is achieved, argues Jerryson, because its practitioners and its analysts create a fantasy version of Buddhism: “fictitious people and practice–virtual religious models, morally airbrushed to enhance the message” (p. 185). The problem with this mythic Buddhism is that its dark side is ignored: extreme phenomena such as monks with guns, “soldier-monks”, militarized temples, Buddhist militia. In Thailand, religious nationalism legitimates violence, offensive and defensive, against the enemies of “nation, religion and king”. Monks as spiritual exemplars are credited with the power to purify and order hearts and minds and social relations, as Christine Gray has argued.

This sacred role is not discrete from politics and power. Under Thai state purview, monks have had a political role as emissaries, as agents for building a new national identity and fostering unity. Indeed, the advent of political monks was first set out in the work of Tambiah and Somboon. The Thai state is sacralized as an imaginary repository of pure dhammic practice, which monks politically defend on the front lines with their sacred bodies, as agents of the sangha and state. Anyone who wishes to change the socio-political order, to create division and disharmony, becomes an enemy of the state. In the 1970s Thai communists were enemy Number One; today, it is “separatist” Malay Muslims and “republican” Red Shirts.

To understand the uses of Buddhism we must not view it as abstracted from social relations, a philosophically or spiritually pure form of knowledge, but rather as an historical practice of truth and a technique of power shaping people’s socio-political identities and mundane reality. Its sacred “ultimate truth” as performed is neither other-worldly nor discrete from oppressive forces which justify and legitimate violence.

Buddhist Fury marks a significant advance in understandings of Thai racialized identity and the Buddhist spiritual dimensions of ultra-nationalism and racism. Why are ethnic Malays, categorized as “khaek”, excluded from Thainess but Sikhs included? It seems that Chinese can become Thai overnight but not “farang”, in spite of their alluring lighter skins, idealization and privileged status in Thai society. Jerryson’s bold hypothesis is that the primary cause of violent conflict in Thailand’s far South is racial inequality; state-led exclusionary policies together with conditions of poverty give rise to separatist strife. Malay Muslims are neither ethnically Thai, nor religiously Buddhist (p. 144). There is thus a need to examine the relationship among religion, historical Siamese and Thai notions of race and contemporary racism in the South.

The category of “khaek” subsumes multiple ethnicities–South Asians, Malays, Arabs–aggregated by the shared attribute of having dark skin, which is read by Buddhists as a sign of impurity and inner badness. It is not ethnicity that causes racism, exclusion and inequality in Thai society but, rather, the ways in which race and religion are combined in identity formation. Religion, central to Malay Muslims’ identity, excludes them from Thainess. Malay ethnic identity has become fused with Islam. But it has not always been so; history reveals the existence of Malay Buddhists.

Thai racism identifies Malay Muslims as “khaek” not by using a Western biological notion of race, but rather one based on skin colour, a sign of spiritual purity. Chinese are included within Thainess on the grounds of shared customs and Buddhist beliefs, socio-economic roles and status. Thai Buddhism is the normative measure of identity and civility, which others lack. It becomes a racial identity. “Khaek” is a racialized identity including a religious marker, a negative classifier of “people of another religion”. Jerryson points out, following Charles Keyes, that “khaek” are associated with the Buddhist evil figure of Mara, demons and their human followers, imagined as dark-bearded figures representing Malays and South Asians. The Thai social order embodies racialized distinctions and statuses, and to this degree it has traces of the Hindu caste system as re-worked in Thai Buddhism and politics.

Jerryson’s analysis reveals the weakness of David Streckfuss’s path-breaking account of the Siamese “creative adaption” of Western racial categories to resist colonization by forging a new notion of identity combining nation and race and citizenship into “chat”. However, pace Streckfuss, this does not entail a Western physio-anthropological category of race. Streckfuss fails to note the religious dimension in the new concept of chat: being a Thai Buddhist, a racialized religious identification. Having a dark or light skin is not just a sign of a poor socio-economic status, or an aesthetic issue. It is an indigenous Buddhist classifier of moral and spiritual purity. Buddhism is not, in the end, an exception to religious traditions that assign people to superior and inferior racial groups.

The Brahmin and Buddhist origins of “chat”, in Sanskrit “jati”, signify rank, caste, family, race and lineage; membership of a “divine race”; becoming or being born a Buddhist. Caste, purity and pollution, the sacred and mundane, are all entailed in the term’s meanings: a spiritual and socio-economic status and the racial formation of superior pure and impure inferior castes. One sign of membership is of course light skin color. “Jati” was taken up in the nationalist ideology of Rama VI to render Buddhism a signifier of being civilized, the member of a superior race, not among the savage others within Siam, on the international imperial stage. Siam needed savages and inferior beings for its appearance of being civilized; ethnic and religious minorities took on this role. Siamese Buddhism became part and parcel of Siamese racial identity through the exclusion of Malay Muslims as “foreign and semi-barbarians” as Chao Phraya Yommarat expressed it, but the inclusion of ethnic Lao, Khmer, Vietnamese and Chinese as they were closer, as Buddhists, to the Siamese race.

Violence stems from racial inequalities rooted in religious and ethnic identifications. Jerryson shows how in a zone of conflict identities become racialized into incarnations of goodness and badness as effects of the trauma of violence. Faith becomes fate when identification is fixed to an essential racialized and primordial religiosity. Buddhism is used to construct the otherness of those who question and oppose Thainess. Regimes of religious and racial truth identify who and what people are, worthy of living or dying. The master narrative of Thai history and the myth of national unity confirm Schmitt’s notion of the political entailing/deciding of existential friend-enemy relations by positing a permanent Thai self which needs a bad or enemy other in order to be itself. Enemies “within” are both created and desired.

Buddhist Fury also suggests that the legitimacy of “network monarchy” and the inviolability of the kingdom’s sacred “geo-body” might not be the primary issue in the southern conflict. Malay Muslims are not attacking the monarchy, but rather the racist and religious form of “colonial” rule and domination emanating from Bangkok. Malay Muslims are asserting their counter-truth, their history and identity, which have been silenced and subjugated. What is occurring is not a sovereign struggle over land but a conflict over ethno-religious identity and forms of life. Malay Muslims are attempting to “de-colonize” hearts and minds of religiously enforced Thainess.

Furthermore, Jerryson’s analysis suggests that Buddhism is not a Thai coping strategy for handling anxiety and uncertainty–about succession, Malay-Muslim autonomy in the South, the future of Thai society. Rather, it actually generates fear and insecurity to feed religious nationalist fantasy. Thus Buddhist religion is used to maintain a state of exception that manifests itself as permanent crises and “holy war” against impure others. Buddhist-inspired violence in the far South of today’s Thailand is, rather than an abhorrent exception to the rule of peaceful and sacred uses of the religion, just a modern version of an Asian Buddhist tradition of defensive war and warrior monks.

Tim Rackett is an associate professor on the faculty of HELP University, Kuala Lumpur. He has spent more than a decade and a half in Thailand researching Thai Buddhism, religious nationalism and forms of truth and rule.

References

Gray, C. Thailand: The Soteriological State in the 1970s. Doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago, 1986.

J├╝rgensmeyer, M. Terror in the Mind of God. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, third edition, 2003.

Jerryson, M., and M. J├╝rgensmeyer, editors. Buddhist Warfare. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

McCargo, D. Mapping National Anxieties. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2012.

Somboon Suksamran. Buddhism and Political Legitimacy. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University Research Dissemination Project, 1993.

Streckfuss, D. “The Mixed Colonial Legacy in Siam: Origins of Thai Racialist Thought 1890-1910.” In L. J. Sears, ed., Autonomous Histories, Particular Truths: Essays in Honor of John R. W. Smail. Madison: University of Wisconsin Center for South East Asian Studies, 1993.

Tambiah, S. J. World Conqueror and World Renouncer: A Study of Buddhism and Polity in Thailand against a Historical Background. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Tambiah, S. J. Buddhism Betrayed? Politics and Violence in Sri Lanka. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Victoria, B. Zen at War. New York: Weatherhilt, 1998.

Zizek, S. The Puppet and the Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2003.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss