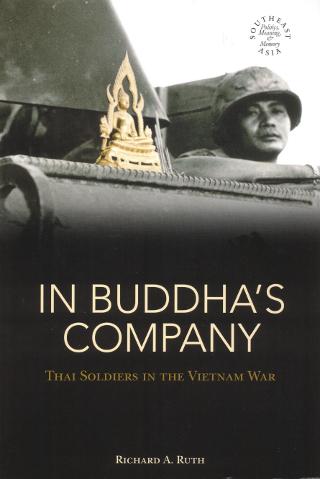

Richard A. Ruth, In Buddha’s Company: Thai Soldiers in the Vietnam War. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, 2011. x+275 pp.

From 1965 to 1972 Thailand aided the American war in Indochina by dispatching 37,644 military personnel to South Vietnam as part of the US State Department’s Free World Assistance Program. After America and South Korea, Thailand’s military contribution was the third largest of the Free World nations. The Queen’s Cobra Regiment, the first combat unit to arrive in 1967, was later supplemented by the Black Panther Division. Both units, located in the same area of operations between the port of Vung Tau and the US Air Force base at Bien Hoa, saw active combat, suffered casualties and fatalities, and killed many Vietnamese communist guerrillas. The aim of Richard Ruth’s study is to restore this forgotten episode in Southeast Asian military history and by doing so, to counter the prevailing historical interpretations of what took place.

At the outset he proposes two views of the Thai volunteer soldiers. According to some historians and to the anti-war movement, Thailand succumbed to pressure from the United States and contributed troops who were paid for by the American government to the tune of $50 million a year. The Thai troops were mercenaries, or so the argument goes, their base at Bearcat Camp a veritable American bubble where the rules of conduct and dominant culture were entirely American. The Americans provided logistical support, including daily rations that the Thais sometimes found inedible, and allowed the Thais to shop at the PX stores in South Vietnam where they could use their per diem and bonus pay to buy hi-fi stereos, colour televisions and other consumer goods. American trainers prepared the Thai troops for their tour of duty.

The contrasting view is that Thailand’s military rulers sent the troops for their own reasons. The Queen’s Cobra Regiment came into existence to serve Thai ends and was not merely a creature of American will. The Thai government at the time rested its claim to power on defence of the country against communist aggression. “I would be the armour that blocked this doctrine from coming into Thailand,” a Thai veteran tells Ruth proudly. Participation in the war ensured that Thailand would continue to receive economic and military aid from the USA, and the junta needed some popular political theatre depicting “shining knights in a dirty regional war” to camouflage the reality of its dictatorship. King Bhumibol’s attentiveness to wounded troops repatriated to Thailand and his attendance at cremation ceremonies for the fallen warriors bolstered the righteousness of the war cause at the time. The official monument to the country’s involvement in the Vietnam War, tucked away from public view at an army base in Kanchanaburi, epitomises the amnesia among the general public that now prevails about Thailand’s role in the conflict.

Ruth then proceeds to break down the mercenary vs. patriot dichotomy and demonstrate the ambiguities in the motivations and attitudes of the Thai soldiers. He leaves the regional security issue to one aside, and he does not broach the searching question of how large quantities of American economic and military aid might have affected the Thai political system by entrenching military guardianship of the national community. Instead, he produces a finely-grained social history of the self-selected group of Thai volunteer soldiers who volunteered for combat. The view of American trainers that the Viet Cong would tear the Thai troops to pieces proved wrong; in an early engagement, the Thais successfully defended their camp against a determined Viet Cong siege. Volunteers in the employ of Uncle Sam they might be, but they were able warriors on the battlefield too.

In their own self-image they were also merciful warriors who understood the South Vietnamese people better than the Americans with their awesome technology and enormous resources for fighting the war. The Thai soldiers developed a rapport with the Vietnamese, more so than with the Americans, because the people they encountered in rural areas were largely Southeast Asian farming folk like themselves. The similarities between Thai and Vietnamese cultures were recognizable. The Thai soldiers were sympathetic to the divided loyalties and apparent duplicity of the South Vietnamese they were defending, and they were sympathetic to the villagers caught in the middle of the conflict. South Vietnam was a feminine country for the Thai soldiers: Vietnamese husbands, sons and nephews had gone off to war, and the absence of these men made it possible for Thai soldiers to take their places as boyfriends, lovers, patrons, and saviours. Some soldiers even identified with the southern Vietnamese guerrillas. They could understand the decision of their enemy to take up arms against the Americans who had invaded and occupied their land. The Thai volunteers also did their part in civic action programs by rebuilding bomb-damaged village schools, operating mobile medical and dental clinics and providing relief for children affected by the war.

Against this empathy with Vietnam and the Vietnamese people ran other currents of feeling of apprehensiveness about dangers in the jungle and the need to protect themselves against snipers’ bullets and the foreign spiritual forces in an unfamiliar land. The trade in amulets and talismans was vigorous, and the double entendre in the book’s main title – the Buddha’s company as combat unit, and the Buddha’s company as protective guardian – makes the point eloquently. A taboo grew up around killing Vietnamese barking deer thought to be conduits to powerful spiritual forces that could harm the Thai soldiers if not treated compassionately. Ruth’s chapters on trading magic for modernity and fighting on the metaphysical landscapes of South Vietnam are especially strong.

One of the stereotypes that Ruth seeks to overturn is that of the Thai soldiers as traders first and as warriors second. Certainly there were war profiteers, opportunists, and hustlers, especially after the Black Panther Division arrived in 1968 and some soldiers became more audacious in their schemes for personal enrichment. Entrepreneurial skills allowed them to excel in dealings on the black market where the going exchange rate was one stereo or refrigerator for a kilogram or two of marijuana. There was also a vigorous trade in firearms (supplied by the Americans to the Thais) in exchange for drugs (supplied by the Thais to the Americans). Ruth argues that these images, prominent in non-Thai histories of the Vietnam War, overshadowed the many examples of valour on the battlefield, sacrifice and local knowledge contributed by the Thai troops.

Ruth’s account is all the more effective for its restraint, but you have to smile at some of the wackier incidents. In 1968 fifty Thai masseuses honoured soldiers returning injured from Vietnam by donating a full nights’ wages to the veterans. During a fashion show in aid of the soldiers some of the models hobbled out on crutches and in slings and bandages to express their empathy. Not all the injuries were combat-related. One soldier had a leg broken not in enemy action but when the PX door was slammed on him in a scrum of soldiers pushing to get inside. Thai soldiers hated waiting in line – “very un-Thai,” said one veteran. The risk to life and limb in order to do some serious shopping was evidently worth it. Alerted to incoming mortar fire, one soldier instinctively took off his flak jacket and threw it over the new stereo he had just bought form the PX.

The Thai army is poorly studied except for the officer corps and its political ambitions. In one sense, this is understandable. Army generals in uniform or ex-military men have been prime ministers in Thailand for over half the time since 1932. Thak Chaloemtiarana’s masterful Thailand: The Politics of Despotic Paternalism, reissued in 2007 by Cornell’s Southeast Asia Program with new material and a postscript, set a formidable standard of scholarship and is still cited. But in the three decades since the book’s original publication, political scientists, including Thai political scientists who follow military affairs, have stuck stubbornly to predictable paradigms about what seemed to matter: promotions to the upper echelons of the officer corps; solidarities, networks and rivalries among graduating classes of the military academy; the military budget and corruption; and strategic matters, terrorism and disputes with neighbouring countries. As tensions increase late in the ninth Bangkok reign, factions in the army affiliated with members of the royal family have become a favourite pastime for army watchers. In contrast, the infantry and its recruitment from rural youth, the impact of veterans on society once they returned home, the army’s role in economic development and civic action, and military education barely rate a mention in the mainstream scholarly literature.

After finishing the book, I was not certain that Ruth had completely dispelled the “mercenary” label. In any case, he has succeeded in humanising the rank and file volunteer soldiers and probing their memories at a historical moment when Thai military leaders have reinstalled themselves at the centre of power for half a decade. He inhabits the soldiers’ world and conveys their experiences, their prejudices, fears and religious beliefs, their indulgences and pleasures, and their interactions with a neighbouring Southeast Asian people treated as an adversary in Thai textbooks. The beauty of this timely book is that it brings to the surface martial themes that have been forgotten as the decades have passed since the 1975 communist victories in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. Dialogue from the interviews and other novelistic touches add colour, and the absence of academic jargon and theory make this an eminently readable book that one hopes will pioneer future revisionist studies of militarism in the Land of Smiles.

Reviewed by Craig J. Reynolds

Published originally on New Mandala, 9 June 2011

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss