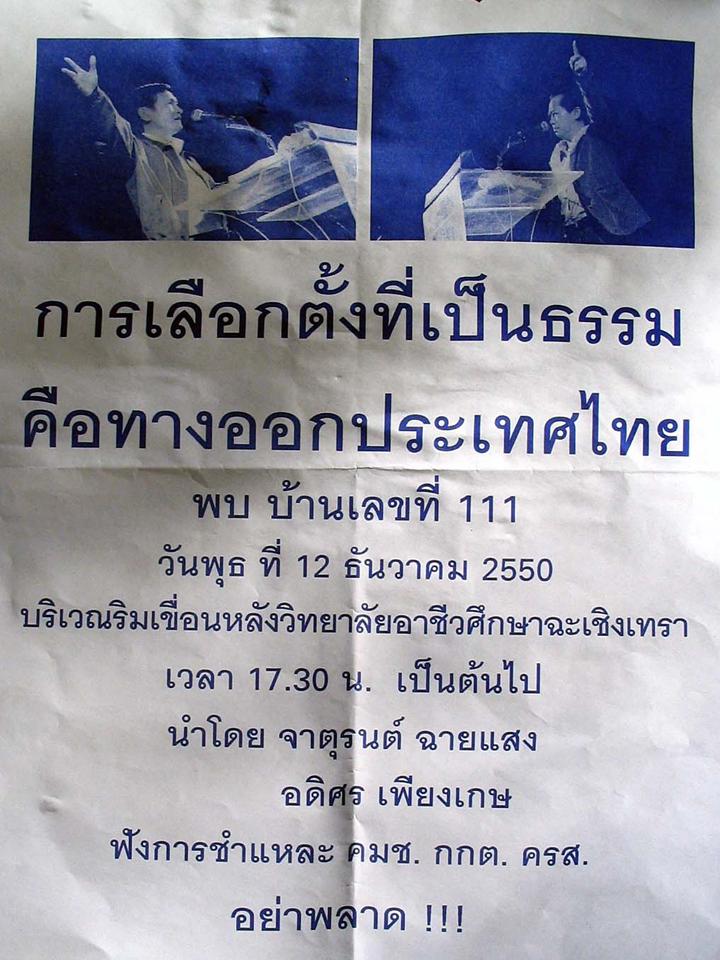

On December 10, 2007, advertising pick-up trucks drove around some areas of Chachoengsao inviting people to listen to speeches by Chaturon Chaisaeng and Adisorn Piangket. Under their new label of “House Number 111” (ban lek thi 111), they were to set up a stage behind the vocational college of Chachoengsao, along the Bang Pakong river. One day later, I found that many shops around the area of the old market (which belongs, by the way, to the Crown Property Bureau, and is thus not managed by the municipality, although it represents the old center of the town) had received leaflets of the group pointing to the main theme of the event, “Fair elections are the solution for Thailand” (picture 1). At the bottom of the leaflet, people are asked “Listen to the dissection of the NSC [National Security Council, the coup group], the ECT [Election Commission of Thailand], and the AEC [Asset Examination Committee]-Don’t miss it!!!”

Picture 1

The number 111 refers to the 111 former members of the executive board of the Thai Rak Thai party. When TRT was dissolved, these members lost certain political rights, according to article 69 of the Political Party Act of 1998 (article 97 in the 2007 version), which says “a person who used to be a member of the Executive Committee of the dissolved political party shall not form a new political party, be a member of an Executive Committee of political party nor be a promoter of a new political party under section 8; provided that within the period of five years as form the date of the dissolution.” This stipulation had the curious effect that the leaders of a party dissolved for being a dire threat to democracy and national security could run in subsequent elections, become MPs, ministers, and even prime minister.

When the coup-appointed Constitution Drafting Assembly and National Legislative Assembly deliberated the new version of the Political Party Act, there were groups of hardliners who wanted to introduce nothing less than a five-year total loss of political rights of the executives whose party had been dissolved by the Constitutional Court. This was deemed “too harsh,” and thus the hardliners had to be satisfied with a newly-drafted article 98, which makes a party leader and his executives also lose their electoral rights for five years. This was applied retroactively.

This change still left space for the 111 previous executive members of TRT, mainly in their reincarnation as the People’s Power Party, to play an active role in the party’s election campaign and thus use their continuing personal popularity in election constituencies to increase PPP’s number of votes and MPs-something the coup plotters and its auxiliary bodies certainly dreaded. However, since executives of PPP had some doubts as to what was actually allowed, they asked the ECT for its opinion. The election commission then did not waste its chance of reintroducing the hard-line stance through the backdoor. In its formal opinion, it pretended that the above-mentioned two articles of the Political Party Act also included a stipulation that prohibited the former 111 TRT executives from speaking at election campaign rallies (thus the ECT partially annulled the people’s constitutional right to express their political opinions), from being pictured with election candidates, and even from being members of any political party altogether. No legal measures could be taken against this opinion, because it did not constitute an administrative act. The ECT maintained that this was merely its opinion and did not have any legally binding force. However, it added that in case anybody would complain about “violations” later, those who had acted against its opinion might have to face legal consequences.

This situation led Chaturon and about five other former TRT executives, such as Adisorn Piangket, his long-time political pal, or Pongpol Adireksarn, to found the group “House Number 111.” Under this label, they had organized a rally in Nonthaburi. The event in Chachoengsao was another attempt at challenging the ECT by setting up a stage and speak on politics, even attack the above-mentioned bodies, without saying anything that could be construed as campaigning for a political party. Former TRT board members in other parties and most of those connected to PPP, however, felt too intimidated by the ECT’s threat and kept quiet. Even the National Human Rights Commission decided that the ECT’s opinion did not violate the human rights of the former 111 board members of TRT.

So how did the event in Chachoengsao proceed?

I arrived at the venue at 17.50 hours. The organizers had arranged for 180 chairs, 40 of which were occupied at this point. In the end, altogether about 400 people listened to the speeches of Pongpol Adireksan and Chaturon Chaisaeng. Adisorn could not come because his father had died. As usual, the social composition of the audience were non-elite people. But then, Chachoengsao’s elite is not that big anyway.

Behind the stage, Chaturon was sitting at a table waiting for his turn. Mostly, he sat alone or with one or two other people. Staff numbers and friends served food and drinks. From time to time, gift baskets were delivered. There were about 30 members from their inner group, including Chaturon’s wife and staff from their office. Anand Chaisaeng, Chaturon’s father, sat in the audience. Picture 2 shows him with the executive chairperson of a tambon administrative organization. In their vicinity sat a kamnan (sub-district headman), who had been a well known hua khanaen (vote canvasser) for the Chaisaengs for many years. At the beginning, he had called me to sit with him, and we had brief talk. Later, when I passed him again, I overheard him telling his neighbor on the bench who I was and that I “pen phak phuak diewkun” (that I belonged to their clique). Konlayut Chaisaeng, the municipal mayor, and Kitti Paopiamsap, the executive chairperson of the provincial administrative organization, sat with some other local politicians farer away from the stage on a bench along the river. A few meters away from them, a member of the provincial election commission observed the event.

Picture 2

Pongpol was the first to give a speech. He complained about the long list of political restrictions they were subjected to, and he criticized the ECT decision (“opinion”) as being too harsh a sentence and that it violated their rights. He was not even allowed to be photographed with his son, who was standing for election in a central province. All this violated article 45 of the constitution (right to express one’s opinions; he mentioned two others that I cannot remember). The ECT’s decision contravened the constitution. He wondered why those commissioners could not understand this since all of them were legal experts.

When Chaturon got on the stage, he received many garlands. At the beginning of his speech, which was not interrupted by applause (perhaps only once), he said that he was on stage as he had always been at election time since many years. However, this time, the situation was rather strange, because there was no logo of any political party and neither its election number. Previously, he would talk only briefly and then give the microphone to Thaksin. Picture 3 shows Chaturon giving a speech at Bang Pakong district during the election of February 2005. In that speech, he emphasized that Thaksin needed many votes and seats in order to form a stable government, and did not have to worry about intra-governmental problems when he had to travel abroad. Picture 4, taken at the event, looks very much different, indeed.

Picture 3

Picture 4

Chaturon then complained that that the ECT had expanded the penalties (given with the TRT’s dissolution based on the Political Party Act). The newspapers always wrote that they had “lost their political rights.” This was wrong. They could still talk and write. (I also have been annoyed about the degree of imprecision in this matter as displayed in the Thai press, be it English or Thai language.) Where did the ECT get the right to prohibit him to talk-where was the regulation? There was no legal basis for its decision whatsoever. However, the political parties running in the elections were afraid, because they feared their dissolution. For this reason, he could not give campaign speeches, and Pongpol could not even be photographed with his son.

Were they, the audience, really those who would decide about the future of the country in the election? In fact, there was only a small group of people with power, that is those who had seized power. They were not ready to return the power to the people, and so the people’s votes had little significance. This group had been trying to interfere with politics as could be seen, for example, from the secret military documents that described projects aimed at obstructing the People’s Power Party. One overall purpose had been to krajai (disperse) the 111 former executive members of TRT. Only after a number of new political parties had successfully been established by some of those members-such as Somsak Thepsuthin (Matchimathipattai), Suwat Liptapanlop (Ruam Jai Thai Chart Pattana), and Surakiat Sathienthai (Phuea Phaendin)-did the ECT act to prohibit all involvement. This showed that from the beginning they had had the intention and a plan to harm only one single political party (PPP). In this context, Chaturon also mentioned the step procedure to destroy Thaksin and TRT devised by the CNS.

Chaturon then spoke for some time about the secret documents, including the decision of the ECT to reject the PPP’s complaint on this matter. The whole point was “lack of neutrality” of the CNS. The rejection showed that, nowadays, anything could be done by referring to national security as an excuse. (Two ECT members, including its chairperson, a close friend of coup-leader Sonthi Boonyaratglin, seemed to have argued that the military’s project against PPP was covered by its task to protect national security.) If they had found the documents to be fake, they would have had to dissolve PPP. Thus, they had figured out a different way of rejecting the complaint.

The 111 former members of TRT’s executive board had lost many of their rights, but not the one to express their opinions. Actually, he could talk about his opinions, but he did not want to cause any problems to candidates and political parties. Nowadays, it was very easy to dissolve political parties, although they were in fact important organizations of the people for joining together and pursuing their political ends and to govern the country. Even when US president Nixon had to resign, the Republican party was not dissolved. Why was only one party threatened, although Somsak, Suwat, and Surakiat had had vital roles in establishing new political parties?

As voters, they should not vote in a way that benefited all political parties evenly (susi) since this would limit their impact even further. The people were constantly intimidated. The country had already suffered tremendous harm to the count of hundreds of thousands of million baht. And this did not even include the question of how many hundreds of millions of baht went into corruption. He was not talking for himself, but for the country. If they were in favor of the coup plotters they should vote one way, but if they opposed them, they should vote another way. If they voted in a susi way, then they would not be those who determined politics. What they would get was the ECT as the government. Thus, “chuai tatsinchai hai dee” (make good decisions).

Only a few months ago, the newspapers had compared him with Abhisit and asked who would be the better prime minister. Today, he could not even vote in the election, although he had done absolutely nothing wrong. This was pralat (odd, strange), but it was this way under phadetkan (dictatorship). Their struggle for democracy had to continue for many more decades. In doing so, they must not fear anybody. The future was in the hands of the people-first of all in the election of December 23.

During his speech, which ended at around 20.30 hours, there had been a few references to Thaksin Shinawatra, to Sonthi Limthongkul, and the PAD. Chaturon did not forget to mention that many of those who had directed the protests had been on the CDA, NLA, and AEC. But for all his somewhat academic eloquence, Chaturon did not include the slightest suggestion that TRT and Thaksin had done anything problematic while in government.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss