Donald Trump’s inauguration couldn’t come at a better time for relations between the US and the Philippines, Nathan Shea writes.

While Rodrigo Duterte’s War on Drugs has led to 6,000 deaths in his first six months, it his perhaps his colourful language towards outgoing US President Barack Obama that has been at the centre of the most extraordinary moments in the former mayor’s short term as president.

Since coming to power in July, Duterte has repeatedly attacked the US broadly — and President Obama directly — bringing about the most significant shift in bilateral relations between the two countries since the final days of the Marcos regime. While at times the vitriol has been framed within a broader narrative of past colonial injustices, it is hard to distance the substance from the personal grievances of a leader paranoid of Western interference and oversensitive to criticism.

The fallout from Duterte’s outbursts has not only been rhetorical, but consequential. Following the September media conference where Duterte allegedly called Obama a “son of a whore”, the US President promptly cancelled a scheduled meeting due to take place alongside the ASEAN leaders conference.

Since this initial instance, Duterte has variously told Obama to “go to hell“, announced a “separation” from the US, and has threatened to terminate the visiting forces agreement that allows for American military personnel to be stationed in the Philippines.

In return, the US embassy in Manila in December announced it was deferring aid packages to the country due to “significant concerns around the rule of law and civil liberties in the Philippines.” The aid package, worth an estimated $US434 million, was to be assigned to expand social welfare programs to alleviate poverty and to contribute to improving the country’s poor road network.

Further worsening relations is the tenacity with which Duterte has sought to counterbalance US influence in the region. He has made ‘fast friends’ with Russia and China, openly courting both President Putin and President Xi for greater military and financial investment in the Philippines. Earlier this month, while personally welcoming two Russian warships in Manila, Duterte professed his hope that Russia would become the Philippines’ ally and protector.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has broken ranks with other Western democracies by partnering with Duterte to progress his ambitious social development plans. In a state visit last week Abe became the first world leader to visit Duterte’s hometown of Davao City.

Taken together, these developments can be viewed as standard geopolitiking, but the broader narrative is one where in his first six months Duterte has successfully steered Philippine foreign policy away from its traditional ally, the US, and into a more balanced, independent alignment. Recent reports have celebrated the securing of 1 trillion Philippine pesos (approximately US$20 billion) in official development assistance, easily accounting for what was withheld by the US last month.

In truth, while Duterte’s outspoken aggression towards the United States has been novel entertainment for observers, it speaks to broader displeasure with the direction of US foreign policy. Obama’s ‘leading from behind’ doctrine might have been popular in some Western liberal circles, but after eight years many have become frustrated with a global superpower unwilling to match ideals with action. Fairly or not, Obama’s foreign policy has become synonymous with a more belligerent Russia, a calamitous humanitarian disaster in Syria, and antipathy to Chinese expansion in the South China Sea. It has also earned a reputation as a country quick to criticise others, while not acknowledging its own failures and inequalities.

Into this void now steps President-elect Donald Trump.

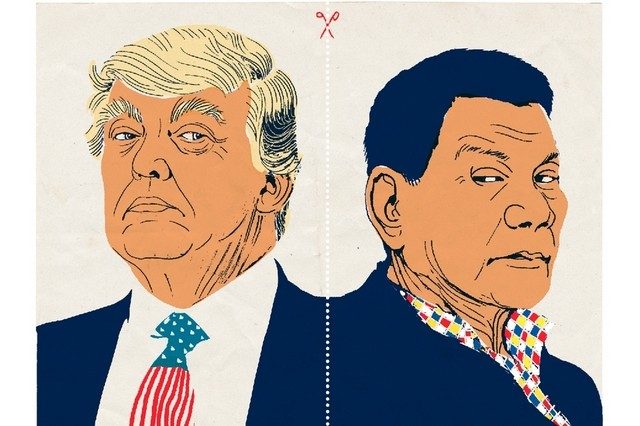

Much has been made about the similarities between Trump and Duterte: they are both men in their early 70s, populists, and prone to explosive outbursts of language not typically seen in the demure landscape of international politics. And while these comparisons are often superficial, early signs between the two bellicose leaders appear to point to a cordial – if not ‘chummy’ – relationship which could signal a new normal in Southeast Asian politics.

In a statement following the US presidential election Duterte wished President-elect Trump “success in the next four years”, saying that he “looks forward to working with the incoming administration for enhanced Philippines-US relations anchored on mutual respect, mutual benefit and shared commitment to democratic ideals and the rule of law.”

Following this, in early December, Duterte spoke of a recent phone conversation between the two where Trump had reportedly praised his War on Drugs. In video footage of the remarks, Duterte recounted that Trump told him that he was “doing great”, expressed a willingness to “fix our bad relations”, and not to worry about the American criticism. “You’re doing good, go ahead,” Trump allegedly said. An invitation was also given by Trump to have coffee when Duterte next visits Washington DC or New York.

Plainly, Duterte’s receptiveness towards President-elect Trump marks a clear departure to the open hostility displayed towards his predecessor. For what it’s worth, in an October interview with Reuters Trump criticised Duterte for showing a lack of respect to its “decades-old ally”, though placed the blame squarely at Obama’s feet. Apart from this, little else has been directly heard from the President-elect on his position towards the Philippines, an outcome that would immediately suit Duterte.

Former British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston famously said that “nations have no permanent friends or allies, they only have permanent interests.” What appears most important to Duterte is US acquiescence to his social renewal program – warts and all – with the biggest of these being the deadly War on Drugs. For the Philippine President, frustrated by the critical gaze of Western leaders, Trump alternatively appears apathetic and disengaged, willing to appease countries outside of the US’ direct political interest. Trump’s denigration of liberal institutions, including NATO, the EU and the UN, further signals a broad disinterest in pan-global human rights.

All of this bodes well for arresting the deterioration of relations between Washington DC and Manila under a Trump presidency. While positive on its own, the broader implications for US influence and human rights in Southeast Asia remain of concern – particularly with two brash, reactive leaders on either side of the Pacific. Recent comments from Secretary of State nominee Rex Tillerson on China’s ambitions in the South China Sea illustrate that the region remains a powder keg of geostrategic posturing not conducive to smooth diplomatic navigation. Regardless, the change of administration in the White House provides the opportunity for a fresh start and offers a more amenable foundation on which to build the US-Philippines relationship moving forward.

Nathan Shea is a research associate and PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne.

This piece is published in partnership with Policy Forum – Asia and the Pacific’s platform for public policy analysis, opinion, debate, and discussion.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss