Editor’s note: this is the first in a series of posts we’re bringing you this week that feature the perspectives of young writers from President Rodrigo Duterte’s home region of Mindanao on two years of Dutertismo.

• • • • • • • • • • • •

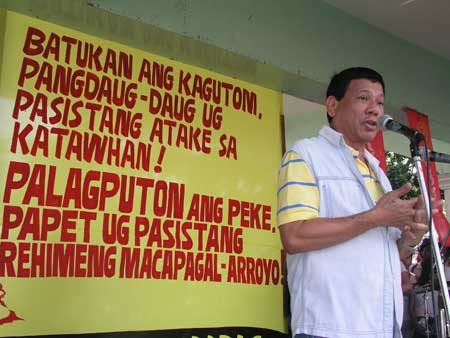

Two years ago, Rodrigo Roa Dutetre was sworn in as the sixteenth President of the Republic of the Philippines. For the first time, a man from Mindanao was elected to be the Philippines’ chief executive.

My social media feed exploded with excitement. My friends from Mindanao posted celebratory messages accompanied with hashtags

#changeiscoming, #changehascome, and #DU30. At home, I heard people declaring they have never been prouder to be Filipino. “I’m a Filipino, and my President is Duterte,” said an Instaquote that went viral.

I could not join friends, family, officemates, in their elation. I did not vote for Duterte.

There is an impression that everyone from Mindanao is a staunch Duterte supporter. I must admit that prior to the start of the campaign, I did consider voting for him. This fact of affinity, that we were from the same origin, mattered to me.

Before his quick ascent to power, Duterte was already well-known within Mindanao because of his rule in Davao City. He transformed Davao, as the story goes, into a hub of economic growth where crime is close to non-existent. Davao City’s reputation reverberates throughout the island. Even my hometown Iligan City, which is about 300 kilometres away by land, could only look to Davao for inspiration. I have met people who visited Davao City only to check out whether the myth is true, and, often, they are not disappointed with what they have experienced.

I also considered voting for him because of family. See, our household has a setup for voting that has been in place for generations. My family, including extended kin, vote as a bloc for local elections. National posts, on the other hand, are all conscience votes. In 2010, our family was split, with some voting for National Defense Secretary Gibo Teodoro, then Senator Manny Villar, my choice and current senator Dick Gordon, and the eventual winner Noynoy Aquino.

In 2016, it was unanimous for Duterte.

I remember my conversation with my mother about this. She told me, “pare-pareho man tanan na ang ni-agi. Lahi si Duterte.” (Everyone who was President was the same. Duterte is different.) My father meanwhile said that like us, Duterte has Maranao blood. Maranaos are the second largest non-indigenous Muslim ethno-linguistic group in the Philippines, concentrated mostly in the two Lanao provinces in Mindanao.

The next president could possibly be of our lineage, my father added. Reading between the lines, my father was implying that blood is thicker than water. National politics in the Philippines has always been a game of musical chairs among the Macapagals, Aquinos, and possibly the Marcoses. It’s time to break the exclusive gene pool of national politics. Our fellow Maranao, Digong, as he is fondly called, can make history and snatch the seat of power from the elites up north.

As a Maranao lawyer working in human rights, I find it challenging to categorise Duterte as pure villain. I come from a context where Duterte’s Davao has long been held as the exemplar of local governance that delivers on its promise to help people in the margins. This is not cheap rhetoric but supported by evidence across decades of Duterte’s rule as city mayor.

Consider the case of children. It was during his term as mayor that Davao City was awarded for excellent provision of public school education. Few could boast of having a 99% literacy rate for children aged 10 years and older, much more having passed in 1994 a local Children’s Welfare Code—the first local government unit to do so. In practice, this means allocating funding for child-focused initiatives and requiring barangays (villages) to include in their respective annual budgets an allocation for not only basic services and protection from violence, abuse, and child labor but also the establishment of a barangay council for the protection of children. Davao was awarded the hall of fame award as child-friendly city having won it multiple times.

The same can be said for his accomplishments for women. Long before the enactment of the Magna Carta for Women in 2010—a landmark legislation based on the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) that prohibits discrimination against women, such as protection from all forms of violence, including those committed by the State, participation and representation in public and private sectors, and equal access for women in education, scholarships and training—Davao led the way when it enacted its CEDAW-referenced Davao Women and Development Code in 1997. While it took until 2003 for it to be fully implemented, it was already moving for its realisation and forged partnerships with women’s groups. It put in place a mechanism for electing women representatives in the city council. It created a permanent office dedicated to mainstreaming gender and development (GAD). The code mandated funds to be allotted for such programs, with at least 6% of agricultural development fund, 30% of official development assistance fund, and 5% of general fund. Thus, its city council does not approve budget without a GAD plan. The Philippine Commission on Women designated the city as a “Local Learning Hub on Gender Training” which brought numerous government officials to Davao City to learn the best practices in the field.

Also look at Duterte’s record in creating policies against discrimination and promoting equality. As more and more people are pushing for local ordinances to treat people equally and protect them from discrimination on the basis of their gender identity, sexual orientation, religious affiliation or belief, colour, race, or descent, in the absence of a national legislation local ordinances have become a safe haven for anti-discrimination advocates. And for people already living in Davao, this was granted in 2012 when as vice mayor Duterte led the city council in having passed an anti-discrimination ordinance. He was quoted as even saying that Davao should be envisioned as a “city where everyone similarly circumstanced are similarly treated in rights conferred, opportunities given and obligations imposed.”

From a human rights perspective, the passing of policies pursuant to international conventions, which the Philippines signed and ratified, are crucial. They are the first step to promote, respect, protect, and fulfil human rights at the local level. The second step is the acknowledgement that these laws and policies would be useless unless they are enforced. For this, the reputation of the city to strictly enforce its ordinances, such as the smoking ban in 2002 (which also preceded the national law in regulating tobacco and last year’s nationwide executive order regulating public smoking), is attributed to Duterte’s political will as well as the constant engagement of advocacy groups.

However, it would be impossible to talk about Davao from a human rights perspective without reference to the legacy of Duterte’s iron fisted approach to governance.

Even before Duterte landed the cover of Time Magazine where he was called “The Punisher,” talks about his connection to the Davao Death Squad has been the subject of discussions in the region, albeit in hushed tones. This Death Squad, or DDS, was rumoured to be targeting suspected criminals who committed petty crimes to the most serious ones.

I grew up hearing these stories when I was in high school in Iligan. Back then, I did not know the difference between a suspect and a person who has a criminal record. I know, however, that killing people, without giving them the opportunity to defend themselves, or what we call as due process, is morally reprehensible. And that is enough to merit skepticism against Duterte’s rule.

It is debatable whether Davao under Duterte was a dictatorship. What is clear is his power was inescapable. As an autocrat, he was able to cherry-pick which human rights he prefers to support and which ones to neglect.

Recall that at the time that he started his tenure in the late 1980s, the country was transitioning from the Marcos dictatorship into an emerging democracy. Scholarly literature points to the phenomenon of emerging democracies abiding to human rights covenants, which, it seems is applicable to Davao’s case, as in the case of children, women, LGBTs, and other minorities.

But a local tyrant can decide which rights and liberties he can curtail. Davao under Duterte has seen the erosion of civil and political rights, as in the case of harassment of journalists and media workers, and deprivation of suspects of their day in court for a fair hearing and trial by executing them in public.

The last two years of Duterte’s presidency could not be worse than what human rights advocates imagined. Duterte has openly called for summary executions of drug dealers and users, as well as human rights activists who defend them. Police figures put drug-related fatalities until end of May 2018 at 4,649 while critics think the figure is much higher to at least 20,332. iDefend, an alliance of several human rights organisations, states that “two thirds of the killings are carried out by what we call police vigilantes—masked agents without uniforms but with clear ties to the security forces” or even by the police officers themselves summarily shooting anyone suspected dealing or using drugs

This war on drugs has targeted primarily urban poor urban dwellers, including children, than the wealthy, mirroring the experience of other countries, and saw three mayors and one vice mayor killed.

The high number of cases, and disregard for life and due process of laws, has prompted two human rights lawyer groups to file a case in the Supreme Court of the Philippines, questioning the constitutionality of the government circulars to conduct its war on drugs with its use of words to “negate” and “neutralize” targets, and in April 2018, the Supreme Court affirmed its earlier order issued to the Philippine National Police to submit data on the almost 4,000 killings. To my mind, Duterte did this. He made matters worse as he unleashed his rhetoric against drug addicts and criminals.

Duterte’s controversial style of governance goes beyond the bloody drug war. He barred a reporter covering Malacañang who was critical of him. He told soldiers to shoot female communist rebels in the vagina. The Justice Department, presumably upon his instructions, included the name of the Filipina UN special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples on a list of alleged terrorists, prompting the UN human rights chief to defend her in a press conference and question Duterte’s mental stability. He told the police not to cooperate in any investigation conducted by the UN as regards the killings related to the war on drugs. He declared the country’s withdrawal from the International Criminal Court. He ordered the deportation of a seventy-one-year-old Australian nun engaged in community work in some of the country’s poorest regions.

The flurry of spectacular news reports has been confusing. Even more confusing are the reasons for his unwavering popularity. The people who chose him knew he was like this, and they’re happy with their choice.

When he won, much of the expectations were for him to transform the Philippines into a scaled up version of Davao City. He has taken the same strategy when it comes to drugs and crime, but seemed to have forgotten his accomplishments with respect to the modern human rights movement.

Philippines beyond clichés series 1 #2: Dynasties

Do political dynasties hold back The Philippines' economic development? Nicole Curato investigates this question with Assoc Prof Ronald Mendoza.

On the day of Duterte’s inauguration, I shared a photograph of the President and his children. “I did not vote for you Mr President but I shall support you as you are the President of the Philippines. Prove your critics wrong because this nation, with your supporters at the forefront, sure needs to rise rise rise! 👊🏽 👏🏽 🇵🇭 #LetsUnite,” I posted on Facebook.

Two years down the road, I feel exhausted for myself and the nation. The mayor he was before is not the president he is now. I belong to the minority of Mindanaoans who felt that he could have done better over the past two years, but I still hope for a silver lining.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss