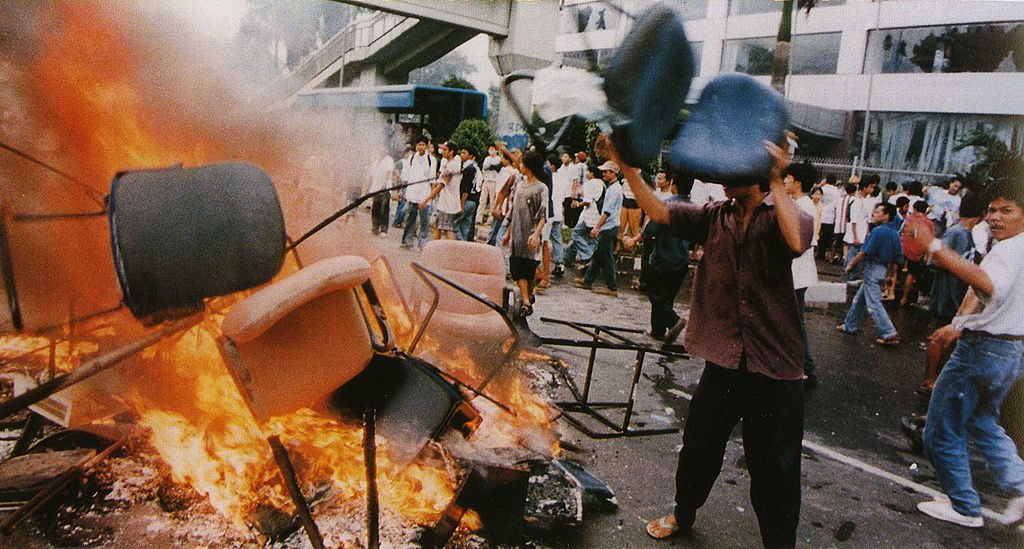

The mass demonstration that gripped Jakarta earlier this month stirred up memories of the May 1998 riots, Danau Tanu writes.

On Friday 4 November, a 100,000-strong demonstration organised by the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) took hold of Jakarta demanding for Ahok, the Chinese Christian governor, to be investigated for allegedly insulting Islam. It left many of us who grew up under the New Order regime nervous, and brought back memories of 1998 when riots ravaged major cities across the archipelago.

To the relief of Jakartans, no riot materialised this time around. But Jokowi cancelled his trip to Australia, scheduled for that weekend, on account of the domestic situation. Duncan Graham suspects it was a ‘snub supreme’. I don’t think so.

In May 1998, Suharto nonchalantly left the country to attend a Group of 15 meeting overseas while student demonstrators occupied the parliament building. He smiled on camera with foreign dignitaries like nothing was the matter back home. That put the final nail in his political coffin. Suharto had to cut his trip short to return to a nation in chaos. The rest is history.

But Jokowi is no Suharto. He may have spent all of that Friday ignoring the protests, appearing on television, going about his work visiting construction sites, as though oblivious. But flying overseas after a tense night would have pushed things a step too far. Like the rest of us, he remembers 1998.

In the lead up to the day of the demonstration, we were confident that the current government, under Jokowi’s leadership, could maintain order. Even so, some of us, particularly the ethnic Chinese, stayed home or took refuge in the houses of relatives located away from the city centre – just in case.

Days before, I had tried to organise a small weekend gathering for some Chinese-Indonesian friends. By then messages spreading fear were circulating on social media. One friend messaged back to our Whatsapp group in a state of veiled panic, “Let’s see how the demo goes. They say it’s going to be serious. Praying for peace.”

Another, more gung-ho, friend laughed it off. “It won’t turn into a riot. The FPI are the only ones demonstrating. The organisations that aren’t getting paid to demonstrate have all been lobbied by Jokowi via the MUI (Indonesian Ulema Council).” It is known in Indonesia that demonstrators are often taken advantage of by political interests and paid to protest. But confident that Indonesia was in secure hands, this friend planned to attend a meeting that Friday in the business district near the site of the planned demonstrations.

When Friday rolled around, I went to my parents’ house anyway, just to be on the safe side. Their house is deep in the south of Jakarta, a neighbourhood that had been spared in the rioting 18 years earlier.

As the evening prayer echoed later that day, news outlets announced that the demonstrations were coming to an end. There had been a brief clash, but crowds were dispersing. Indonesia had come a long way – riots were nowhere to be seen. So I returned to my apartment only to switch on the television to find that the crowd was moving towards the parliament building located near my neighbourhood. They were going to camp there overnight. They were from out of town. They were not satisfied. They wanted a presidential assurance that Ahok would be investigated.

The parliament building was where the students had camped in 1998. The euphoric image of student protestors sprawled across the green butterfly-shaped roof is still fresh in our minds. But the demonstrators of this Friday night were not the same as the students from two decades before. This time there was no dictator to depose. It seemed that political motivations were being couched in religious sentiment and ethnic animosity. Only the imagery was the same.

As the night wore on, the news live-streamed images of citizens and the police clashing with rocks and tear gas in North Jakarta, near Ahok’s residence. A store was looted. All the news channels braced for potential mayhem. But I was too tired to return to my parents’ house. Instead, I packed my wallet, car keys, clothes and passport in one bag and left it next to the door. Just in case.

The year after Suharto stepped down, I wrote my honours thesis on the 1998 student movement. In the process, I got distracted by the pages and pages of reports published in the Indonesian broadsheets about women who were raped in the open during the riots. It was a sickening read.

One report told of a young Chinese woman who was dragged out of her apartment, gang raped, and thrown against the back of the elevator wall. Her family watched, helpless. As I packed my ‘escape bag’, I reminded myself that the tight security in the building would be meaningless if 1998 happened again. Besides, I am female with small ‘Chinese eyes’. I shoved a pair of sunglasses into the bag.

The morning after, the regular programs were back on television. The only mention of the night before was that the demonstrators had cleaned up after themselves – big news in a country riddled with garbage problems. Images of litter-less streets were shown – evidence that the demonstrators were, in the words of one newscaster, “more mature” now. Nevertheless, one of my Chinese friends refused to return to her home in the city centre that day. “I was here in 1998. I don’t trust the media,” she messaged.

Many other Jakartans remained unaware that things had gotten tense the night before. While the city had gone to sleep, parliament representatives met with the demonstrators in the small hours of the morning. The crowd was coaxed into leaving at around 4am. The president finally held a press conference an hour later.

Over a week later Ahok was named as a suspect in the blasphemy case. Amnesty International, like clockwork, issued a statement condemning it. Is Jokowi succumbing to pressure? Or is he “buying time”, as the singer-turned-politician Ahmad Dhani (that dude who wore a Nazi outfit) accuses him of?

The political safari of late shows that Jokowi indeed has domestic issues to attend to, as 1998 looms in the background for those who remember.

Danau Tanu completed her PhD in Anthropology and Asian studies at the University of Western Australia on mobility and international education in Indonesia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss