Versi Bahasa Indonesia dari tulisan ini bisa dibaca di Tirto.id.

“Rocket attacks happened, and I don’t know… I ran away and didn’t see anyone from my family”, said Faruq, an Indonesian boy in al-Hol camp, Syria in a BBC report, February 2020. He and two other boys, Yusuf and Nasa, aged around 10 to 12 years old, were separated from their parents and family when ISIS’s last stronghold, Baghouz, fell in March 2019. They have lived in al-Hol camp ever since, without guardians. Until this day, we do not know what the future holds for these children.

In February 2020, the Indonesian government announced it will not repatriate citizens who joined ISIS in Syria and Iraq. The government, however, opened the possibility for repatriation of unaccompanied children under ten years of age on a case-by-case basis. It has been more than a year since the announcement and no significant progress has been made, partly due to the worsening COVID-19 situation in Indonesia. Meanwhile, Indonesian children continue to live under squalid conditions amidst health and safety crises inside the camps.

Indonesian pro-ISIS groups also exist in other ISIS-claimed territories, including in the Philippines, Iraq, and Afghanistan. The latter case is timely to discuss. A small number of Indonesians have arrived in the ISIS ‘Khorasan’ since 2017, some bringing their family along with them. As of early August 2021, there are eleven Indonesian pro-ISIS detainees in Kabul, Afghanistan, at least three of them are children under ten years of age. There has been discussion about their transfer from Afghanistan’s National Directorate of Security (NDS) prison to the custody of the Indonesian embassy, but this was cancelled after the Taliban takeover on 15 August 2021. The Taliban reportedly freed some pro-ISIS and pro-al-Qaeda prisoners, including the eleven Indonesians. No one knows what happened to the children or what kind of life they must face in the midst of the ensuing chaos.

Dire conditions in Syrian camps

A recent IPAC report shows there were 555 Indonesians in al-Hol, al-Roj, and some Kurdish prisons, according to a census that took place in June 2019. Children were a large part of that population. There were 367 Indonesian children under eighteen, 75 per cent of whom were under ten. ISIS was active in recruiting and mobilising families, including women and children, after its establishment in mid-2014. Hundreds of Indonesian families were sold on the high hopes of living under the true, prosperous, and just Islamic state. The reality turned out to be far from it. The capital city, Raqqa, fell in 2017 and Baghouz was taken over in March 2019. Thousands of their supporters were displaced to camps and prisons managed by US-backed militia, the Syrian Democratic Front (SDF).

The living conditions were already poor, but became even more dire as COVID-19 hit. Access to nutritious meals, water, hygiene, and medical facilities is scarce. The restriction of mobility during the pandemic further delayed distribution of aid and basic necessities, and forced some health clinics to shut down due to limited medical personnel. Consequently, eight children died within a week in August 2020 due to malnutrition and limited health facilities. It was reportedly three times higher the death toll rate for children since the beginning of 2020.

Confinement in camps is also affecting the children’s psychological well-being, partly due to post-war trauma, but also because of the constant threats of violence inside the camps. Pro-ISIS women have been reported to burn tents or beat to death those accused of violating ISIS law, as seen in the case of Sudarmini, a pregnant Indonesian woman who was found beaten to death in July 2019. ISIS sleeper cells are smuggled inside, conducting killings and even a public beheading in early 2021, escalating the tension inside the camp. Sexual violence is also prevalent, despite limited documentation.

The future is gloomy for these children. They receive no education but only indoctrination from pro-ISIS women. The UN and other humanitarian organisations have repeatedly call on governments to repatriate their nationals, especially children, but efforts so far remain insufficient. In March 2021, the National Anti-Terror Agency, BNPT, said it will conduct on-site identification and verification processes once the travel ban is lifted, but the chance is slim today amidst the worsening COVID-19 situation worldwide. The data verification is one thing, but there is a lot of work that needs to be done before repatriation takes place, and it should start immediately.

Government’s challenges

Repatriation of the children is not an easy process. Challenges include the definition of children eligible for repatriation, citizenship and data verification, risk assessments, diplomatic issues, and competing bureaucratic interests.

The Indonesian government has hinted at the possibility of repatriation for unaccompanied children under ten years of age. But such a requirement can be problematic on the ground. For instance, in the case of Faruk, Yusuf and Nasa, who were already close to or older than the ten-year-old threshold when the interview took place: have their rights to get a better life and future already vanished? Faruq, Yusuf, and Nasa are not isolated cases. The IPAC report shows there are 34 unaccompanied children under eighteen; nineteen were under ten years of age as of June 2019.

There were also 22 child brides, some with babies and toddlers, who possibly will not be regarded as “children” anymore, according to the citizenship law. Their children, however, will be granted Indonesian citizenship. The child protection law mandates the state protect every citizen under eighteen, regardless of their marital status, and thus the child brides, along with their babies, should be accorded full rights as children. But again, with the narrow eligibility for child repatriation, will they have a chance to come home?

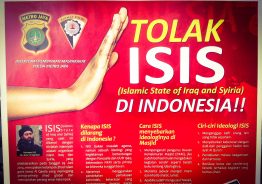

Indonesia’s ban of ISIS was motivated by more than fear of returning fighters, writes Dominic Berger.

Why Indonesia banned ISIS

Data verification can be a real challenge as many camp residents lost their legal documents due to war or had them confiscated when they first arrived in IS territory. Those who decided to stay may use false identities or have deliberately destroyed their legal documents. The Indonesian government could use other methods of data verification, for instance by working with the Kurdish government who has done census and collected biometric data for some nationals in 2020 and 2021.

Another obstacle is diplomatic. Indonesia maintains ties with the Syrian government under Bashar al-Assad, which does not recognise the Kurdish-led territory where the camps are located. Building communication and cooperation with the Kurdish government is seen as potentially harmful to Jakarta’s relationship with Damascus. Nevertheless, in August 2017, Indonesia successfully worked with the Kurdish government in Rojava in repatriating its 18 nationals, without affecting the relationship with Assad’s government. Humanitarian organisations in al-Hol also pointed out that working through proxies is possible, even repatriation through Damascus, as done by Albania, Kosovo, Russia, Sudan, and Uzbekistan.

Repatriation increasing the security risk?

The most complex challenges in repatriation are institutional differences in their approach and interests. Security agencies such as the police, BIN, and BNPT, continue to weigh the risk of child repatriation. Other institutions, especially those with a greater focus on child protection, are more concerned with the methods of repatriation, not whether it should be done.

The perception of a risk to the state increases with age. Infants and toddlers may pose little risk to Indonesia’s security, but older children are assumed to have greater risk as they may receive indoctrination and military training from ISIS. ISIS indoctrination is ongoing and targets young children inside the camp. The government needs to move fast because the longer it delays, the fewer children will be under ten years of age. A thorough risk assessment therefore needed, as well as good work with the children’s family and community, and a well-planned and sustainable rehabilitation and reintegration programs.

Indonesia has experience in handling child deportees and returnees in 2017, as well as the domestic cases of children exposed to extremism, as seen in the case of seven children of the 2018 Surabaya bombing. Lessons learned from post-conflict intervention projects in Aceh, Ambon, and Poso can be an important reference for future work. Children from Syrian camps might face entirely different situations, with different degrees of trauma. But prior-hands-on experience is a good starting point.

The rehabilitation and reintegration programs also need to be supported with a good policy framework. The Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection tried to fill the gap by issuing a 2019 ministerial regulation on guidelines for protecting children from radicalism and terrorism, which includes steps for prevention, reeducation, and provisions for social, psychosocial, and psychological rehabilitation for children within extremist networks. However, implementation remains uncertain. On the other hand, The National Action Plan on P/CVE, signed by President Joko Widodo in January 2021, claimed to have incorporated child protection principles, despite no provisions on child deportees, returnees, or those stranded abroad.

All and all, the Indonesian government needs to have a real plan on the repatriation of Indonesian children in Syrian camps, with a clear roadmap and timeline. It can start with a small number of children to ease the monitoring process and develop better rehabilitation and reintegration programs ahead. Unaccompanied children under ten will number less than ten in 2021, and it is a good number to start with. These children cannot wait any longer as they grow up with grievances and disappointment with society and their government under ISIS indoctrination. Bringing them home is the only option that addresses both the humanitarian and security aim of weakening Indonesian links to terrorist networks abroad.

This article derives from IPAC report No. 72 with the same title “Extricating Indonesian Children from ISIS Influence Abroad”, full report can be accessed here.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss