Laying the groundwork for a coup

The seizure of control byThailand’s army is a profound blow to democracy. But one of the ironies of the current political crisis in Thailandis that much of the ideological groundwork for this military intervention has been laid by the so-called “pro-democracy movement.” This loosely organised movement, spearheaded by businessman (and ex-Thaksin crony) Sondhi Limthongkul, has been active in calling for Thaksin’s resignation since late 2005. No doubt, Thaksin has given his critics plenty of ammunition. His government’s flagrant abuses of human rights in the restive Muslim south of Thailand have attracted national and international condemnation. And his notorious “war on drugs” in which extrajudicial killings have claimed thousands of lives is an outrageous approach to policing Thailand’s amphetamine plague. More recently, Thaksin’s legal manipulations to avoid paying tax on a massive personal share sale added fuel to the anti-government forces who have succeeded in staging a succession of impressive protest rallies in Bangkok.

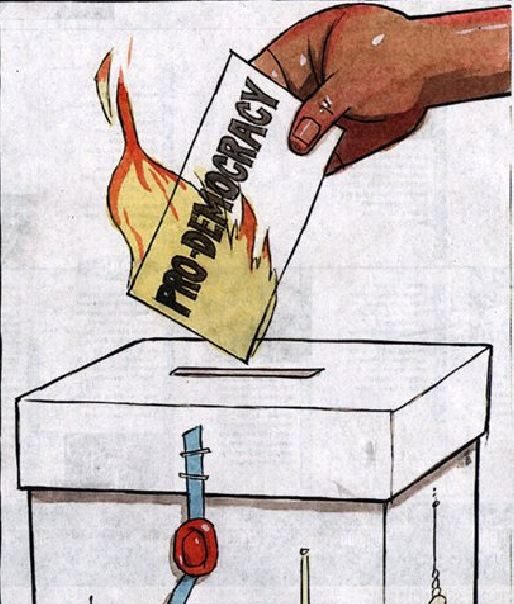

Thaksin’s faults have been widely publicised and vigorously debated. This is as things should be in a modern democracy. But the pro-democracy movement has not been satisfied with democratic debate. When Thaksin called a snap election in April this year the opposition parties boycotted it. Having firmly put their case against Thaksin they were unwilling to face the electorate. Beneath all their claims about electoral irregularities lay the recognition that they would lose the election. Essentially they sabotaged the election, reducing it to a farce. It came as no surprise that the majority vote achieved by Thaksin (compared to the 30 percent “no vote” advocated by the opposition parties) was not acceptable to the pro-democracy forces. That this came on top of a similarly impressive Thaksin victory in the general election little more than a year earlier did nothing to lessen their calls for his head.

Strangely, Thailand’s pro-democracy movement is fundamentally ambivalent about the electoral process. Thaksin’s electoral victories are considered to be illegitimate because they were “bought” from a poorly educated and unsophisticated electorate. There is a lot of talk of vote buying. I have no doubt that Thaksin’s party has been involved in the distribution of funds prior to national elections. I myself was a beneficiary of Thaksin’s generosity, receiving 100 baht (about $4) and a jacket at a meeting I attended with villagers in rural Chiang Mai province. But let’s not forget that all major political parties in Thailand are involved in these conspicuous displays of generosity. Rural people gladly accept these payments–who wouldn’t?–but they are fully aware that there is now no way of tracing direct links between payments and votes. The ballot is secret, ballot boxes are scrupulously sealed and votes are now counted at electorate level. It is impossible to determine the voting patterns in individual villages. Quite simply, rural people accept payments from everyone and vote for whoever they wish.

The pro-democracy movement is also active in condemning Thaksin’s “populist” economic development schemes. “Populist” is a word used in Thailand to refer to policies that allocate resources outside Bangkok and bypass the usual elites. There has been repeated condemnation of Thaksin’s nation-wide village credit fund which is said to have contributed to the political corruption of villagers. While Bangkok is awash with credit card debt, pro-democracy social commentators vilify the provision of small-scale loans to farmers. They see initiatives in local economic development as tantamount to vote buying. The benefits for rural households, who can get loans from a locally managed credit scheme rather than private money lenders, are completely ignored in the Bangkok elite’s rush to condemn Thaksin’s populism.

It is still too early to judge how the pro-democracy movement may respond to the coup. Many will be glad to see Thaksin go, whatever the means. But there is bound to be considerable discomfort that the military has once again entered onto Thailand’s political stage. I wonder if the anti-government advocates are willing to accept that their denigration of Thaksin’s electoral mandate has helped to pave the way for this intervention. The pro-democracy movement has portrayed Thaksin’s stunning and unprecedented electoral support base as being made up of ignorant country bumpkins whose voting intentions are easily swayed by modest handouts. The possibility that the Thai electorate has rationally weighed up Thaksin’s strengths and weaknesses (and decided in his favour) has never occurred to them.

Reports from Bangkok indicate that the soldiers on the street are sporting yellow ribbons on their guns. Yellow is the colour of King Bhumipol who recently celebrated his sixtieth anniversary on the throne. In the hours following the coup his image featured constantly on military-run television stations. Thaksin’s brash style and electoral popularity has been interpreted by many as a threat to the King’s authority. There have been a number of veiled verbal jousts between the two men. Some in the pro-democracy movement have called on the King to take on a more active role in the political crisis. Bangkok’s advocates for democracy have had no hesitation in surrounding themselves with the symbolism of an unelected monarch. One of the key questions that will be debated over the coming months is the role that the palace may have played in this military ambush of a government that has been returned in three successive elections. The palace has reacted angrily to claims in a recent political biography (The King Never Smiles by long time Thailand observer Paul Handley) that the King has exerted an anti-democratic influence over the course of his long reign. With this recent unfortunate turn of events, the King has an opportunity to come out clearly in support of a free and fair electoral solution. But, whatever the King’s actions, will the so-called pro-democracy movement be willing to listen to the voices of Thailand’s majority?

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss