Social determinants of health, coping and quality of life in migrants from Burma in Sangkhlaburi District, Thailand

Leigh Lehane and Mary J Ditton

University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia 2051

Abstract

Social determinants of health, coping behaviours and quality of life were investigated in migrants from Burma living near the Thai-Burma border in Sangkhlaburi District, Thailand. Forty migrants were interviewed in depth in a critical ethnographic study that used an ‘active interpreter model’ to investigate their reasons for migrating; their journeys; life in Thailand and how they coped; and their quality of life. Data from interviews and direct observation were analysed for social determinants of health, coping behaviours, and quality of life. The participants had been forced to migrate, owing to the abusive military regime in Burma and poverty. In Thailand, they suffered from continued poverty; family fragmentation; lack of secure housing, adequate food and clean water; discrimination; difficulties in communication, finding work and accessing health care; endemic corruption; restrictions on movement and land ownership; and threats of deportation. The harsh environment offered few choices, and stress associated with adverse social determinants of health was long-term and cumulative, leading to physical and/or mental illness and a reduced ability to cope. The participants displayed a continuum of adaptation to their situation, and interactions between the migration process, social determinants of health, biological health processes and coping determined their relative quality of life.

Key words: migration, Burma, Thailand, social determinants of health, coping, quality of life

Introduction

Forced migration from one culture to another is a major source of stress (Lazarus 1999: 184; Yakushko et al. 2008). Migrants who flee a conflict situation suffer physical and social deprivations such as loss of human rights, breaches of medical neutrality, and ‘stress, distress and disease’ (Watts et al. 2007).This is the case for literally millions of people from Burma, mainly from minority ethnic groups such as Mon, Karen and Shan, who have been forced to flee to the Thai border illegally, for fear of the Burmese military and suffering from extreme poverty (Human Rights Watch 2004a,b). The problem has existed for decades and is associated with human rights abuses on both sides of the border (Chantavanich et al. 2007).

According to the WHO Country Office for Thailand (2007) and the Thailand Burma Border Consortium (2008), there are four categories of migrants from Burma in Thailand: those in refugee camps, those who seek and obtain work in Thai cities; those who live in Burma and commute daily across the border to work in Thailand; and those who live around the border areas in permanent ethnic community clusters within villages. This paper is concerned with those in the latter category ┬╛ migrants who are willing to do dirty, dangerous and difficult jobs in an attempt to eke out a living; for example, in agriculture, garment making, building construction, domestic duties or sex work (Appleyard 1992).

There has been no previous research dealing with the ‘individual biographies’ (Farmer 2005: 41) of migrants such as these, describing the experiences and emotions that led to their migration, the migration process itself, efforts to settle and work in Thailand, and day-to-day setbacks and struggles to survive. The broad issue is both topical and important in the contemporary world ┬╛ that of the human suffering and ill-health of people forced to migrate from the political and economic environment of one nation-state to another. The narratives of the participants in this study put flesh on the dry bones of social determinants of health (SDH), a topic that is increasingly recognised as being at the very foundation of human rights and public health.

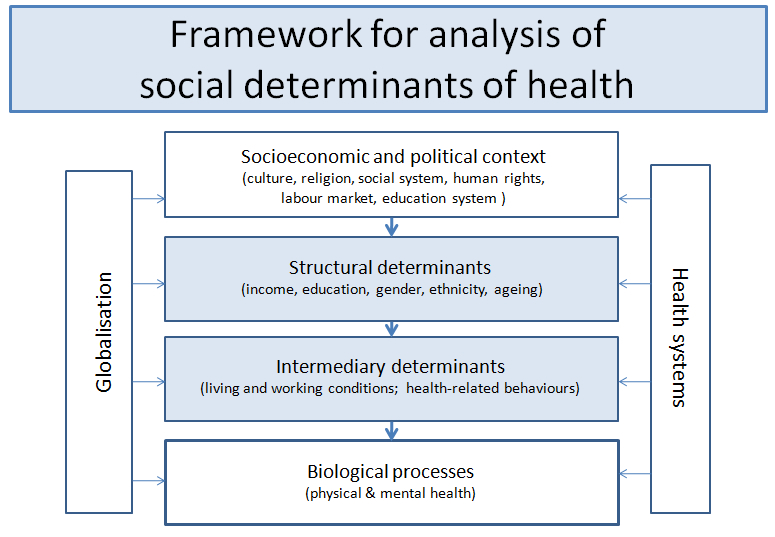

SDH are the conditions under which people are born, grow, live, work and age (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, CSDH, 2007, 2008). They are shaped by the socioeconomic and political context, which determines the distribution of power, money and resources and ultimately affects health (Marmot 2006; Sanders 2009) (Fig. 1). Multiple and long-standing adverse SDH result in stress that can become chronic, and include factors such as poverty; breakdown of family and social relationships; inadequate shelter; lack of food and clean water; and inaccessible health services. Within such environments, coping choices are constrained by limited resources including health itself; coping skills; social support; and material goods (Lazarus & Folkman 1984: 179). The ways in which individuals appraise situations and cope with stress under such conditions are important in determining their relative quality of life (QOL) (World Health Organization, WHO, 1997; Keith & Schalock 2000).

Fig. 1. Framework for analysis of the social determinants of health. (Adapted from Marmot 2006.)

Methods

Sangkhlaburi District of Kanchanaburi Province, with an official border crossing to Burma at Three Pagodas Pass (Fig. 2), was chosen as the research site because there are thousands of migrants from Burma with uncertain legal status living and working in the area (Chantavanich et al. 2007). A Thai NGO (Pattanarak Foundation) offered support.

Fig. 2. Map of Thailand showing the research area, Sangkhlaburi District, close to the Burma border.

The critical ethnographic study (Foley & Valenzuela 2005) was conducted from February to April 2009, after feasibility and immersion studies had been done and institutional ethics approval granted. The migrant participants (20 male; 20 female, ranging in age from 20 to 85 years) were selected on the basis of those most likely to contribute to the study (Stake 1995: 4тИТ5) and were therefore not necessarily representative of the population as a whole. They were from seven ethnic groups from Burma ┬╛ Karen (20), Mon (9), Burman (6), Hindu (2), Lao (1), Chin (1) and Arakan (1) ┬╛ and the length of time they had lived in the border area ranged from decades to a few months. They lived in minority ethnic communities, which are common in villages near the border (Human Rights Watch 2004b; Thailand Burma Border Consortium 2008), or in Sangkhlaburi town. Except for two participants, who had obtained Thai citizenship, all were undocumented migrants. One participant was born in Thailand to migrant parents, but was undocumented and therefore not a Thai citizen.

An ‘active interpreter model’ (Pitchforth & van Teijlingen 2005)was usedto investigate the participants’ reasons for migrating, the migration process, experiences of life in Thailand, the health status of themselves and their families, and their QOL. The principal interpreter was Karen and lived in the research area and was known to, and trusted by, many of the participants. Fluent in Burmese, Karen and English, she was trained to be an active member of the research team as well as acting as a language translator. Many key stakeholders involved in the migrant problem in Sangkhlaburi District, such as staff from various non-government organisations (NGOs), were also interviewed.

The principal author and interpreter interviewed the participants in depth for 1тИТ2 hours once, or on two or three occasions several days apart. The semi-structured interviews focused on SDH and allowed participants to talk freely and at length about issues that were important to them. Because most interviews were three-way conversations with language translation, there was adequate time for note-taking and direct observation of body language and the immediate environment. Data were transferred to computer files each evening, and recurring themes were explored in subsequent interviews using specific probing questions (Minichiello et al. 2008: 100). As the interviews progressed, similar information began to emerge from different participants, which was an indication of ‘saturation’ (Lincoln & Guba 1985: 265).

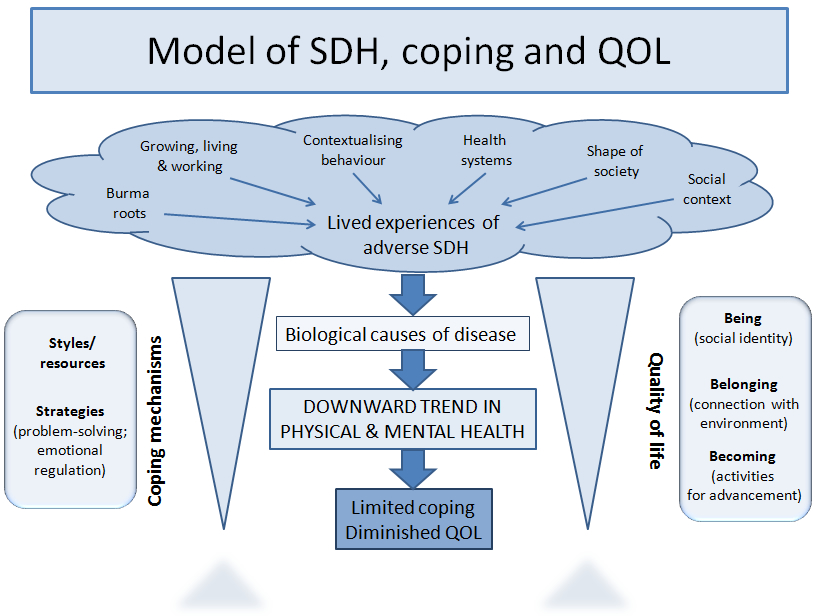

The narratives, together with direct observations that had been recorded during the interviews, were coded (Strauss & Corbin 1998: 101тИТ120), for the most part, under categories similar to those used by the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH 2007); i.e. the growing living and working; contextualising behaviour; health systems; shape of society; and the social context. However, because of the trauma most of the participants suffered before they left Burma, we considered it necessary to add an additional first category, called ‘Burma roots’, to investigate the background of the participants in Burma and the experiences that motivated them to migrate to the border area. This proved an essential first step in putting into context the later experiences of the participants living as migrants in Thailand, or very close to the Thai border.

The data were analysed for SDH (CSDH 2007, 2008) and coping behaviour (Lazarus & Folkman 1984; Snel & Staring 2001) to investigate the lived experiences of SDH of the participants and how they coped in Thailand. The data were then analysed subjectively by the principal author for QOL using the dimensions ‘being, belonging and becoming’ (Centre for Health Promotion, University of Toronto 2009). A positive score for ‘being’ meant good physical and mental health, self-control, self-esteem, and personal values; for ‘belonging’, good adaptation to the migrant life and contribution to family and village life; and for ‘becoming’, active efforts to improve the lives of themselves and their families. Those participants given positive score for each of the three dimensions were assessed as having a good QOL. Participants scoring two positives and one negative for being, belonging and becoming, in any order, were placed in the ‘higher-medium’ QOL group. Two negatives and one positive resulted in participants being placed in the ‘lower-medium’ group; and negative scores for each of the three dimensions resulted in ‘poor’ QOL categorisation. Grouping the participants in four QOL groups in this way (good, high-medium, lower-medium and poor), helped determine the factors that assisted some migrants to cope better than others.

In analysing for QOL it was necessary to use relative, rather than absolute, QOL criteria for the migrant participants. Further, since it was a qualitative study, the numbers of participants placed in each category was not necessarily representative of the migrant population as a whole.

Living and coping with adverse social determinants of health

All of the participants, except a young woman born in Thailand, left Burma because of human abuse and war; poverty and hunger; or social ostracism. Many had endured forced labour and had witnessed the killing of family members. One young man told me how the sister and brother who had been born before him died tragically in Burma while he was still a child:

In 1988 my sister was at the market selling sticky rice and was shot. We never found out who did it, or why . . . the military did not trust teenagers and believed my elder brother, who worked in a nail factory, was a rebel associated with KNU [the Karen National Union], although he was not. They took him away, often for a week at a time, and bashed and tortured him, trying to get information. Each time he would come back very ill and depressed. After months of this treatment he faded away at home, not eating and drinking and just lying depressed on his bed. Doctors could not help [and he died].

The journey to Thailand was difficult and sometimes dangerous. The migrants came in small groups through the jungle, often leaving family members behind:

It was a long way and we had to hide from soldiers and sleep on the ground. We took an ox cart and stopped between midday and 2 p.m. for the cattle to rest. During this time we would quickly cook rice and find vegetables in the jungle. We would stop at villages and hear news of the military’s movements so we could avoid them.

Some participants had relatives who had migrated to Thailand before them, which helped smooth the way:

My wife’s brother was already in Sangkhlaburi and sent us a motor bike [to the border]. Two of us dressed up as peasants and managed to get through the checkpoint [between Three Pagodas Pass and Sangkhlaburi] by bribing the guards with Burmese cigarettes. The other brother walked with others around the checkpoint in the jungle. We went to my wife’s brother’s house in Sangkhlaburi and did some networking with other people from Burma in order to find a job. We had no papers.

Some younger participants were trafficked into jobs such as prostitution and factory work. A young female sex worker, who subsequently escaped to work freelance and became infected with HIV/AIDS, told me:

I paid 3000 baht[1] and was told I would be taken to a domestic job. However, I was taken directly to a sex-workers’ house on the Thai side of the border at Three Pagodas Pass. I was not paid because I owed the broker for my transport and was given only a little rice to eat.

The migrants lived in villages on public or private land in ethnic clusters on the fringes of villages, or in Sangkhlaburi township. Most of the participants knew no Thai people and did not speak Thai, and socialising within and between minority ethnic groups provided vital support. Annual ethnic ‘festivals’ and Buddhist festivals ┬╛ large social gatherings with loud music and dancing ┬╛ were popular; and funerals, with help usually provided by Buddhist monks, regularly provided another reason for groups to gather.

I sometimes go to friends’ houses to talk, but do not eat with them because I have no money [in order to contribute]. Once a year there is a festival in the village, and if there is the funeral of a rich man with plenty of food, music and dancing, I like to go to these.

Migrants generally built their own houses, usually from materials scavenged illegally from the forest. Most were made of bamboo, were neither weather-proof nor mosquito-proof, and were often overcrowded. Among the ‘poorest of the poor’, a woman who lived with an ill husband and two infants in a small (2 m2), single-roomed bamboo hut with thatched roof told me:

My house does not have a good roof and we sleep in the rain. We cook under the house because there is no kitchen. There are many mosquitoes so we have a smoke fire under the house at night.

None of the participants, even the few living in Sangkhlaburi township, had access to a sustainable supply of clean water. Often water had to be carried long distances. While some participants bathed in the river or at a well, others washed in their huts using small amounts of water. In some places where water was scarce and had to be carried a long way, bathing and clothes-washing were rare events, and children in particular had dirt-encrusted skins and often suffered from head-lice infestations. Further, only where water was piped from lakes or rivers to dwellings could there be sufficient water for a pour-flush latrine and adequate removal of human waste. More than half the participants interviewed did not have access to a latrine that could be flushed with water, even with a hand dipper. The best situation for many participants living in bamboo huts was a pit latrine, or hole in the ground, even if it had to be shared between many residents. Often pit latrines were many metres away from the dwellings. If these were not available, people simply went into the jungle to defaecate and used bamboo sticks instead of toilet paper.

One of the oldest participants told me:

There is no water available, except from the river [several hundred metres away, and down a steep hill]. Once a day I walk down to bathe in the river and I carry water back for drinking (which I boil) and for cooking rice. I carry the water in a plastic container in a bag. I need a stick to walk, and I don’t know how long I can go on doing this. I am afraid of the dogs, which do not like me and worry me.

Rubbish accumulated, largely through lack of any means of disposing of it. Some huts were connected to electricity, but they generally had only one light bulb and no refrigeration. Candles used in others were a fire hazard, and two participants had lost houses through fire in this way. A few participants had motorbikes. Public transport, if it was near enough to access, was expensive, and torrential rain often made roads impassable.

Hunger was commonplace, and protein was a luxury. It was common for participants to rely on fish or shrimp paste for protein for most of their meals, as they could not afford regular chicken, eggs, fish, or pork to add to their rice. A number of participants could not afford to feed their children adequately. One man reflected:

My eldest daughter went into the jungle during the day looking for bamboo shoots to sell. She needed only 20 baht for a can of sweetened condensed milk, which lasted the baby 5 days. When we could not afford condensed milk, the baby was fed sugar and water.

A sole parent, a mother with several dependent children, lived by scavenging saleable items from the forest, and was desperate:

I am 55,000 baht in debt, which I try to pay back at 2000тИТ3000 baht/month, but the interest rate is 10% per month. Initially I borrowed 10,000 baht for food and school expenses when I had no work. Now I have to pay back one loan by taking out another. I pay 320 baht for a tin of rice that lasts 3 days. The children beg vegetables from a farm and they very rarely have eggs, meat or chicken. They eat vegetable leaves and shrimp paste. We try to have fish once a month. I sometimes give the three youngest children 3 baht for a snack from the shop. I often do not eat myself. I smoke, but do not drink or chew betel nut.

Poverty, owing to lack of jobs, was the greatest challenge. The options for work in the formal economy were dirty, difficult and dangerous jobs and not favoured by the Thais. Participants who were physically and mentally able to work, and had work, generally seemed happy to earn money, even if it was a pittance. Such workers were often blatantly exploited by their employers. Employment rights and occupational health and safety measures were non-existent. One woman worked on a farm for many years for 50 baht/day:

I took my children with me when I worked on the farm. I used to hang the baby in a hammock from a tree near where I was working. I worked on the farm all through being treated for TB, except for the first 2 weeks, when I had to stay in hospital. Later I was sacked because I became a Christian when I was in hospital and wanted to leave the farm to attend church on Sundays. My husband had another job [besides working on the farm] cutting trees along the side of the road. He was electrocuted through wires in a tree, fell to the ground and died. His boss gave me 700 baht because he died.

Participants who could not obtain work in the ‘formal’ economy were forced to undertake illegal or criminal activities in order to have enough food to eat: these included scavenging in reserved forests for food and for items to sell such as bamboo poles and thatching material; stealing; moving cattle and goods such as illicit drugs across the border; and prostitution. Being caught in such activities could result in fines, beatings, jail or deportation.

All the participants wanted their children to attend school, ‘so they can have a better life than I have had’. Children of migrants from Burma were permitted to attend Thai Government schools. Further, during the research period (2009), the Thai Government removed school fees. However, the children were still required to wear uniforms and shoes, and buy books, which was often an expense their parents could not afford. Transport to and from school was also difficult and expensive. If migrant children could not afford lunch at school, or afford to take a small amount of rice for their own lunch, this was sometimes provided free. However, many migrants were reluctant to enrol their children at Thai Government schools because of the formality of the enrolment process and language difficulties. Most felt more comfortable sending their children to informal schools run by small NGOs (such as Children of the Forest) or more-formal education provided by the Kwai River Christian School at Huaymalai township, a few kilometres from Sangkhlaburi township. Some boys, including orphans, received schooling in monasteries.

Non-citizenship was a bar to ownership of land, and obtaining Thai citizenship was extremely difficult. Most ‘illegal’ migrants in the Sangkhlaburi District have either ‘10-year papers’, or colour cards representing differences in migrant status, which allow them to stay and work in the District if they give no trouble and apply for Thai citizenship eventually. Two participants had attained Thai citizenship by paying bribes, but several others had neither colour ID cards nor papers. A major benefit of attaining Thai citizenship is that of having a ‘golden’ (health insurance) card. Without this, migrants are supposed to pay for health services, or pay about 1900 baht/year for health insurance. Nearly all the participants had stories to tell about coping strategies to obtain cards:

I obtained a blue card when I was 18 and had been in Thailand about 10 years. Now I have been granted Thai citizenship and have a Thai ID card. I had to pay bribes for these cards and feel fortunate to have got them. I think it was helped by the fact that I was of Hilltribe origin. Many migrants are desperate to obtain Thai ID for travel and work purposes and often ID cards change hands illegally when someone dies. This is difficult, especially for adults, because they are photo ID cards!

Although some of the participants had lived in Thailand for decades, all suffered from discrimination and corruption, and said they felt ‘shame’ at being migrants. Cumulative stresses were reflected in marriage breakdowns. Multiple ‘marriages’ were common, and informal marriages were particularly detrimental to women, who were left with families to support. There were no government social support systems for the aged or disabled, and the old and vulnerable were neglected as healthy family members sought work elsewhere. NGOs, church groups, and Buddhist monks provided a vital safety net for some families, but could not cope with the sheer numbers needing help.

The tropical climate of Sangkhlaburi provides an ideal environment for intestinal parasites and areas of jungle are a breeding place for mosquitoes. This contributed to a high burden of physical disease, which was additional to psychological stresses and illness caused by SDH such as experiences in Burma, migration, and living in poverty as a vulnerable underclass in Thailand. Many of the participants and their families were not healthy. They suffered from serious infectious diseases (HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria); injuries from work or motorbike accidents; heart disease; excessively high or low blood pressure; obesity and diabetes; alcoholism; respiratory and gastro-intestinal conditions; arthritis; cancer; physical disabilities; and depression and other mental illness.

However, unless illness was life threatening, health was given a much lower priority for action than seeking work and food. Many participants were tolerant of illness and used private and public health care services only when they were seriously ill and after they had explored spiritual and traditional remedies. Further, when participants did seek health care it was not easy. There was no optical or dental care, and at least one participant removed his own teeth when necessary. Unregistered migrants such as most of the participants do not have health insurance. They are entitled to free emergency care only, except for tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS treatment, and vaccination for children. Poverty, language difficulties, not knowing what services were available, fear of deportation, transport costs, and cultural differences deterred many participants from seeking public medical care.

One of two young female sex workers interviewed was disturbed mentally as well as being physically ill at the time of the interviews. She was anxious and distressed. She said she did not speak to her neighbours anymore, and thought everyone who walked past was a spy. She would not contemplate going to hospital:

I cry a lot and feel life is meaningless. I also laugh loudly a lot and friends think I am crazy for doing this.

Sangkhlaburi Hospital was generally used by participants and their families only for emergencies such as malaria in children and injuries resulting from motor vehicle accidents. Other serious cases of disease and life-threatening emergencies such as obstructed labour, neonatal respiratory infection, septic abortion and advanced cancer were sometimes beyond the scope of NGO programs and the Kwai River Christian Hospital at nearby Huaymalai, and could be referred to Sangkhlaburi Hospital. However, there were few, if any, medical specialists in Sangkhlaburi township, and patients requiring specialist treatment were sometimes referred to Kanchanaburi Provincial Hospital:

My wife died of breast cancer when she was 45. When she first noticed the lump, she was afraid to go to hospital, and went back to Burma for treatment with traditional medicine. When this did not help, she went to Kwai River Christian Hospital. Then they sent her to Sangkhlaburi Hospital on [the back of] a green taxi truck. Sangkhlaburi Hospital [could not help and] sent her to Kanchanaburi [Provincial] Hospital for treatment [mastectomy and chemotherapy]. I paid what I could, which was about 5000 baht.

Migrant children born in Thailand are entitled to apply for Thai citizenship at age 15 years, provided they have papers that authenticate their births. Sangkhlaburi Hospital was used by migrants who could afford to give birth there, in order to obtain birth certificates. An advantage for migrant women who had their babies in the public hospital, or who could afford to pay the hospital, was that of having fallopian tubes tied to prevent further pregnancies, or having a contraceptive injection that was effective for 3 months.

The migrants were well aware of the importance of authenticating births and coped in different ways to get around the Thai authorities:

My daughter was born by home birth in [my village]. Since her mother had Thai ID she will become a Thai citizen at 15. I paid bribe money to the village headman, who helped me get papers for her birth. Sometimes migrant parents with no papers get a person with Thai ID to sign the birth certificate as the father, and subsequently the child gets Thai ID at 15.

Paying bribes was commonplace in order to survive in Thailand, whether it was to obtain birth certificates or ID cards, work illegally, pass through checkpoints, or escape arrest and fines. They were not always paid in cash:

He [my brother-in-law] paid 5000 baht to the police to have a 45-day jail sentence dropped. If people pay enough to police, urine samples are changed to ones that are drug-free.

I gave beer to the forestry people in order to remove bamboo from the forest.

As well as paying bribes, other problem-solving coping strategies included doing any job for money; being good, reliable employees; having a number of jobs, growing vegetables, or raising animals, for food on land that did not belong to them; borrowing money for rice in hard times; leaving families to move around Thailand illegally to find work; learning the Thai language; and ensuring their children went to school.

Those who could not cope, including some who were too old or ill to work, exhibited negativity, denial or anger, and sometimes depression or other mental illness. These participants sought sympathy from NGOs or begged; gave their children to orphanages when they could no longer feed them and send them to school; and used props such as tobacco, betel nut, alcohol, legal and illegal drugs, gambling, and paying spiritual healers in attempts to regulate their emotions. Detrimental health behaviours included denial of having HIV/AIDS; alcohol abuse; risk-taking on the road; consumption of highly processed, cheap snacks; excessive gambling or drug-taking; and violence.

In an atmosphere of fear and poverty, it was not surprising that substance abuse, and sometimes gambling were used in efforts to relieve stress. Many participants smoked ┬╛ tobacco was cheap ┬╛ and some drank cheap rice whisky and used illicit drugs manufactured on the Burma side of the border, mainly methamphetamine, or ya-ba. Many participants chewed betel nut daily, and offering betel nut to visitors was a common practice. Gambling was less common, and appeared to be a masculine activity:

Since I have been in Thailand I have done some gambling on a sort of roulette wheel. Ninety percent of boys who work in factories at Three Pagodas Pass get drunk and gamble on their one day off a fortnight. Some have even sold their motorbikes to keep gambling, and some take drugs.

Women, as well as men, turned to alcohol for comfort and to help them sleep when they could afford it. For some, this form of emotional regulation seemed to be harmless, or even helpful:

I do not like men and do not want another husband. If I am unhappy and can afford it, I buy beer or rice whisky. This stops me thinking, and I can sleep.

Quality of life

It is not surprising that, under the conditions described above, only a minority of resilient participants were able to cope well enough to ensure even a reasonable QOL. None had a ‘good’ QOL by Western standards, and thus assessment of QOL was relative to the other participants only. Assessment of ‘being, belonging, and becoming’ dimensions resulted in 10 participants being placed in the good QOL group (6 males and 4 females), 5 in the higher-medium group (4 males and 1 female), 6 in the lower-medium group (2 males and 4 females) and 19 in the poor QOL group (9 males and 10 females).

Good physical and mental health was an essential criterion for a positive score for the ‘being’ dimension of QOL (good health, self-control, self-esteem and personal values), and this was the obstacle for the majority of participants achieving three ‘plus’ scores and a good QOL rating. In addition, without good health, it was difficult for participants to score positively for either ‘belonging’ (good adaptation and contribution to family and village life) or ‘becoming’ (active efforts to improve the lives of themselves and their families), and thus achieve a higher-medium or lower-medium QOL ranking, although some did this. Participants who scored badly on all three dimensions were placed in the poor QOL group.

Those assessed as having a (relatively) good QOL were considered to be those who coped best. They had good health, earned an income, and sometimes had a supportive Thai employer. They were neither young nor old, but of working age; had good family and social relationships; and often held strong spiritual beliefs. They made deliberate efforts to be cheerful and worked hard, maintained close family relationships, friendships and social networks, and clung to Buddhism, Christianity or belief in spirits for comfort and hope. They joked, day-dreamed (e.g. of winning the lottery), or played sport. By contrast, those analysed to have poor QOL generally suffered poor health, were extremely poor and lived a dependent, day-to-day existence. They tended to have low self-esteem, problems with social relationships, and were unable to contribute to family and village life and plan or take action to promote a better future.

Apart from health status itself, factors evident from the data that were linked to QOL were age; stable employment; good family and social relationships; Thai citizenship; strong religious/spiritual beliefs; gender; ability to speak Thai and/or English; and parenting and early background.

Health was undoubtedly the most important factor associated with a good QOL, and therefore good coping. Only about one quarter of the participants were in sufficiently good health to work hard and earn a living. This was largely owing to the accumulated burden of adverse SDH most participants had been carrying for so long. At the time of the interviews, about three-quarters of the participants exhibited obvious physical and/or mental illness. These people were unable to cope sufficiently to achieve even a reasonable QOL in the hostile environment.

Age was the next most significant factor relating to QOL and coping. The four oldest, and the two youngest, participants were assessed as being in the poor QOL group, and they were least able to cope with the adverse SDH associated with migrant life in Thailand. They had little or no income, no savings and few possessions, ill health, and were dependent on NGOs, relatives or neighbours for food. Although the elderly had been good copers during their working lives, they had not been able to save anything for their old age in the harsh and hostile environment. The youngest two participants, although they were adults, did not have, or had not developed, good coping styles and social resources to cope with the multiple adverse SDH in their environment.

Stable employment was obviously critical in determining QOL for participants able to work, and a supportive employer was extremely helpful. Those participants who were healthy and of working age were able to cope best because they could work hard, had more control over their employment and living arrangements, and had the best QOL.

Family and social support were vital factors in the lives of the participants in promoting QOL. Those in the good and higher-medium QOL groups were, for the most part, those with stable family relationships and social networks. Heterogeneous social networks within and between ethnic groups created social capital and enhanced coping resources and QOL. However, the poorest and youngest, in particular, benefited least from these. They suffered from neglect, poverty, exploitation and debt-bondage relationships before, during and after migration.

Thai citizenship contributed to a better QOL in two participants, mainly because they could now access free health care, their children would become Thai citizens, they could apply for passports, and they would be permitted to own land. On the other hand, being married to a Thai citizen did not necessarily enhance QOL ┬╛ of six participants who were, or had been, married to Thai citizens, one was in the good QOL group, two were in the lower-medium QOL group, and three were in the poor QOL group.

Religion/spirituality played an important role in providing social support and activities. However, the role of actual religious or spiritual belief was difficult to assess as a factor influencing QOL, although it was certainly important in the lives of some participants, particularly those in the good QOL group.

Being female in this study was inversely associated with QOL, because women were often left on their own to support large families. In addition, the two sex workers suffered from a certain amount of stigma, as did women who were/had been married to men with HIV/AIDS; and the youngest female participant was afraid to go out on her own because she was susceptible to sexual harassment.

Education itself, received either in Burma or Thailand, was not associated with good QOL in six of the nine participants educated to secondary or tertiary level. This was largely because of the overwhelming influence of health, which restricted coping styles and strategies, and also the fact that even the educated participants had limited control over SDH for growing, living and working in Sangkhlaburi ┬╛ including the two who had attained Thai citizenship ┬╛ because of their low SES status and their feelings of being members of an unwanted underclass. However, speaking the Thai language, or English, was an advantage for employment purposes and for networking outside restricted ethnic groups.

Most participants in the good QOL group had experienced a favourable early environment. They spoke fondly of their parents, the way they had been nurtured and taught when young, and how this had helped them in later life. Others in poorer QOL groups spoke of harsh early environments and loss of parents when young.

Discussion

Millions of migrants from Burma have entered Thailand in the past three decades (Human Rights Watch 2004; Thailand Burma Border Consortium, TBBC, 2008). Nevertheless, there is little material improvement in the health and human rights of the migrants in Thailand, where they continue to be exploited as cheap labour. Migration and development are interconnected (De Haas 2008), but development proceeds only when conditions allow migrants to benefit from their labours and send remittances back to their home countries, and return home with new knowledge and ideas. In the case of migrants from Burma living in Thailand, migration is forced because of intranational conflict in Burma, the migrants accept any work they can find, and are afraid to return home. Currently, of up to 3 million migrant workers in Thailand, people from Burma represent about 80%, and the actual numbers are further swelled by family members (Human Rights Watch 2010, pp. 3, 19; footnote p. 19). Migrant workers contribute billions to the Thai economy (Amnesty International 2005; Chantavanich, Vungsiriphisal & Laodumrongchai 2007; TBBC 2008), but only about one-quarter are legally registered to work (Martin 2007).

This study demonstrates the vulnerability of the young and old, in particular, in developing countries where there are few welfare provisions. For the stateless migrants from Burma in Thailand, this is especially the case. These migrants are assisted by charitable work of the Thailand Burma Border Consortium (TBBC) and other NGOs, but their needs far exceed the budgets of the organisations and there is no end in sight to the requirement for these services (TBBC 2008).

Within this general context of forced migration, poor development and poor welfare conditions, this study emphasises the constrained choices migrants have in attaining the best QOL possible. These choices are made in a corrupt environment. For example, officials must be bribed to proceed with granting normal entitlements such as the right to seek citizenship and permission to move from area to area to find work. Engaging in drug trafficking or prostitution are risky ways of earning good money in a largely lawless situation. The middle-aged, or those who can work, have the greatest range of choices, while the young, the old and the ill are ‘left behind’.

The participants in this study displayed a continuum of adaptation to the migrant situation, and multidimensional and dynamic interactions between migration, SDH, biological health processes and coping determined their QOL. Whereas in this context adverse SDH were cumulative and continuous for the participants, QOL was more subject to change. The QOL assessments in this study were like ‘snapshots in time’ for each of the participants, and unfortunately QOL was likely to become less favourable for them as they aged under the cloud of adverse SDH (Fig. 3). The model presented in Figure 3 expands Marmot’s (2006) framework for analysis of SDH (Fig. 1) by showing that the active engagement of the individual with the environment in the social context in which he or she lives relates health to coping and QOL. The fact that age, gender and genetic makeup also influence health and coping helps explain why some people are affected by adverse SDH sooner, or more severely, than others. Problem-solving coping strategies described in this paper (adaptive, maladaptive, long-term, short-term) centred around the migrants’ lived experiences, which were all SDH.

Fig. 3. Model of social determinants of health, coping and quality of life constructed from this research.

QOL at the individual level is linked with health (WHO 1997; Bowling 2005), and criteria for QOL correspond well to the SDH, which were devised to provide governments with targets to improve population health (Marmot 2005). SDH are more important to health status than medical care and even personal health behaviours, and are the best predictors of individual and population health (Raphael 2003). Social and psychological circumstances such as long periods of anxiety and insecurity cause stress that accumulates, increasing the chance of poor mental health and premature death (Wilkinson & Marmot 2003: 24). The effectiveness of health-related behaviours, or coping mechanisms for emotional regulation, determined the outcome of psychological factors on the health of individual participants in this study.

How people cope, or manage stressful events, depends on their genetic makeup, and resources such as social support, optimism, and self-esteem. Low socioeconomic status and a harsh early familial environment have consistently been associated with poor coping, and substantial research links low socioeconomic status to both physical and mental health (Taylor & Stanton 2007). It could be expected that effective coping would be particularly difficult for migrants who have painful memories, live in poverty and fear, and have limited choices in an environment saturated with corruption. Participants in this study were ‘stuck’ in their current lifestyle, with few options for improving their situation or going back to Burma. The majority lived a day-to-day existence feeling afraid and insecure and lacking normal comforts enjoyed by citizens with human rights, employment rights, and health rights in the form of accessible and affordable health services. Their priorities for decision-making followed the pattern presented in Maslow’s basic pyramid of needs (Maslow 1970: 104): physiological needs were considered first, followed by a need for security, social needs, and, last, psychological needs. While a few were able to adapt well to the migrant situation, others could barely cope. Breakdown of family relationships, violence, depression or more severe mental illness were the result. Participants and family members with poor emotional regulation tended to be those who were most haunted by their memories of Burma and were the most driven by fear and its consequences.

Despite global aspirations to fight poverty and the health inequities of marginalised, disadvantaged people (WHO 2007; CSDH 2008), a vast amount remains to be done and some communities are ‘falling between the cracks’. In Pathologies of Power, Farmer (2005: 19) argued that SDH outcomes amount to the social determinants of the distribution of assaults on human dignity. Recent research showed that there is little chance that the Millennium Development Goals will be achieved in the migrant population of Sangkhlaburi District by the target date of 2015 (Ditton & Lehane 2009). Without social protection, and with the unremitting assaults of adverse SDH eroding choices and QOL, it is not surprising that this migrant group is beset by physical and mental illness.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of Pattanarak Foundation for their initial support; the principal interpreter, Ni Mar, who was a student at Rangoon University at the time of the student uprising in 1988; and Mrs Mary Jarrott, who assisted with the presentation of figures. The work was self-funded by the principal author.

References

Amnesty International. (2005) ‘Thailand: the plight of Burmese migrant workers’, viewed 5 September 2005, <http://web.amnesty.org/library/pdf/ASA390012005ENGLISH/$file/ASA3900105.pdf>.

Appleyard, R.T. (1992) Migration and development: a critical relationship, Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 1, 1, 1тИТ18.

Bowling, A. (2005) Measuring Health: A Review of the Quality of Life Measurement Scales, 3rd edition, Berkshire: Open University Press.

Centre for Health Promotion, University of Toronto. (2009). QOL Concepts: The Quality of Life Model; The Quality of Life Profile: A Generic Measure of Health and Well-being, viewed 22 December 2009, <http://www.utoronto.ca/qol/concepts.htm>.

Chantavanich, S., Vungsiriphisal, P. & Laodumrongchai, S. (2007) Thailand policies towards migrant workers from Myanmar, Thailand: Asian Research Centre for Migration, Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University, and the World Bank.

Commission on Social Determinants of Health, CSDH. (2007) Achieving health equity: from root causes to fair outcomes: interim statement, World Health Organization, viewed 15 September 2007, <http://www.who.int./social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/csdh_interim_statement_07.pdf>.

CSDH. (2008) Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization, viewed 30 March 2010, <http://www.who.int/entity/social_determinants/final_report/csdh_finalreport_2008.pdf espace.connectingforhealth.nhs.uk/articles/final-report>.

De Haas, H. (2008) Migration and development, a theoretical perspective, Working Paper No. 9, International Migration Institute, James Martin 21st Century School, University of Oxford.

Ditton, M.J. & Lehane, L. (2009) Towards realizing the health-related Millennium Development Goals for migrants from Burma in Thailand, Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 4, 3, 37тИТ48.

Farmer, P. (2005) Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights and the New War on the Poor, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Foley, D. & Valenzuela, A. (2005) Chapter 9. Critical ethnography: the politics of collaboration. In Denzin, N.K. & Lincoln, Y.S. (eds) Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed., Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage.

Human Rights Watch. (2004a) Human Rights Watch World Report 2004. Human Rights and Armed Conflict, USA, Human Rights Watch, 417 pp., viewed 5 May 2010, <http://www.hrw.org/wr2k4/download/wr2k4.pdf>.

Human Rights Watch. (2004b) Out of sight, out of mind: Thai policy towards Burmese refugees, vol. 16(2), viewed 13 March 2008, <http://hrw.org/reports/2004/thailand0204/thailand0204.pdf>.

Human Rights Watch. (2010) From the tiger to the crocodile: abuse of migrant workers in Thailand, viewed 12 November 2010, <http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2010/02/23/tiger-crocodile?print>.

Keith, K.D. & Schalock, R.L. (2000) Chapter 31. Cross-cultural perspectives on quality of life: trends and themes. In Keith, K.D, & Shalock, R.L. (eds) Cross-cultural Perspectives on Quality of Life, Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation.

Lazarus, R.S. (1999) Stress and Emotion, New York: Springer.

Lazarus, R.S. & Folkman, S. (1984) Stress, Appraisal, and Coping, New York: Springer.

Lincoln, Y.S. & Guba, E.G. (1985) Naturalistic Inquiry, Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Marmot, M. (2005) Social determinants of health inequalities, Lancet 365, 1099тИТ1104.

Marmot, M. (2006) Progress on Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Power point presentation at Commission on Social Determinants of Health Meeting in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 5 September 2006, viewed 30 March 2010, <http://www.determinantes.fiocruz.br/pps/apresentacoes/CSDH%20Update%205%20Sept%20Rio%20de%20Janeiro.ppt>.

Martin, P. (2007) The Contribution of Migrant Workers to Thailand: Towards Policy Development, Bangkok: International Labour Organization.

Maslow, A. (1970) Motivation and Personality, New York: Harper & Row. In Palfrey, C. (2000) Key Concepts in Health Care Policy and Planning, Hampshire and London: Macmillan.

Minichiello, V., Aroni, R. & Hays, T. (2008) In-depth Interviewing, 3rd ed., Sydney: Pearson Education Australia.

Pitchforth, E. & van Teijlingen, E. (2005) International public health research involving interpreters: a study from Bangladesh, BMC Public Health 5, 71тИТ88.

Raphael, D. (2003) Addressing the social determinants of health in Canada: bridging the gap between research findings and public policy. Paper given at The Social Determinants of Health Across the Life-Span Conference, Toronto, November 2002, viewed 31 March 2010, <http://www.irpp.org/po/archive/mar03/raphael.pdf>.

Sanders, D. (2009) Chapter 14. Globalization, social determinants, and the struggle for health. In Labonté, R., Schrecker, T., Packer, C. & Runnels, V. (eds) Globalization and Health: Pathways, Evidence and Policy, New York and London: Routledge.

Snel, E. & Staring, R. (2001) Poverty, migration, and coping strategies: an introduction, European Journal of Anthropology 38, 7тИТ22.

Stake, R.E. (1995) The Art of Case Study Research, Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage.

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, Newbury Park, London, New Delhi: Sage.

Thailand Burma Border Consortium, TBBC. (2008) Programme Report, viewed 12 November 2010, <http://www.tbbc.org/resources/2007-6-mth-rep-jul-dec.pdf>.

Taylor, S.E. & Stanton, A.L. (2007) Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health, Annual Reviews of Clinical Psychology 3, 377тИТ401.

Watts, S., Siddiqi, S., Shukrullah, A., Karim, K & Serag, H. (2007) Social determinants of health in countries in conflict and crisis: the Eastern Mediterranean perspective. Draft version 2.0, 62 pages. Cairo: Health Policy and Planning Unit, Division of Health System, Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office, World Health Organization, June 2007, viewed 30 March 2010, <http://who.int/social_determinants/links/events/conflicts_and_sdh_emro_revision_06_2007.pdf>.

Wilkinson, R. & Marmot, M. (eds). (2003) Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts, 2nd edition, Denmark: International Centre for Health and Society, World Health Organization.

World Health Organization (1997) WHOQOL: Measuring Quality of Life, Geneva: Division of Mental Health and Prevention of Substance Abuse, World Health Organization, viewed 31 March 2010, <http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/68.pdf>.

World Health Organization (2007) Health in the Millennium Development Goals, Geneva: World Health Organization, viewed 7 March 2007, <http://www.who.int/mdg/goals/en/index.html>.

WHO Country Office for Thailand. (2007), Border health (ThailandтИТMyanmar), viewed 12 April 2010, <http://www.whothailand.org/EN/Section3/Section39.htm>.

Yakushko, O., Watson, M. & Thompson, S. (2008) Stress and coping in the lives of recent immigrants and refugees: considerations for counselling. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 30, 167тИТ178.

Authors of ‘Social determinants of health and quality of life in migrants from Burma in Thailand’:

Leigh Lehane* and Mary J Ditton**

School of Health, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales 2351, Australia

* Adjunct Senior Lecturer

** Senior Lecturer

Corresponding author: Leigh Lehane [email protected]

[1] The baht is the unit of Thai currency. At the time of data gathering (February to April 2009), about 35 baht were equal to US$1.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss