I am in my father’s hometown of Temerloh in Pahang, Malaysia, for the Qing Ming Festival (清明节), or the Tomb Sweeping Festival. During this festival, Chinese families visit their ancestors’ resting places in order to pay their respects.

“The graves told stories of geographical and familial ties, folklore and local culture, and spanned the realms of the sacred and profane.”

Its early morning and the cemetery is already bustling with activity. A long line of cars are neatly parked to the side of the narrow road running along the edge of the cemetery. The air filled with the chatter of families, spirals of smoke, and the smell of incense. I have only visited my grandparents’ grave a few times over the past 26 years, but I remember how to get there: descend a short way over the first hill crest and turn right at a large grave of a man and his two wives.

I am looking forward to this occasion for two reasons. First, I have not visited my grandparent’s grave in recent years. Second, having recently attended two heritage tours of Singapore’s historic Bukit Brown Cemetery, I had gained a new perspective relating to Chinese cemeteries, as landscapes resplendent with heritage and histories. The graves told stories of geographical and familial ties, folklore and local culture, and spanned the realms of the sacred and profane. As a geographer interested in how society and landscapes are intertwined, I was struck by how much of a country’s multifaceted histories could be extrapolated from such a ‘landscape of death’.

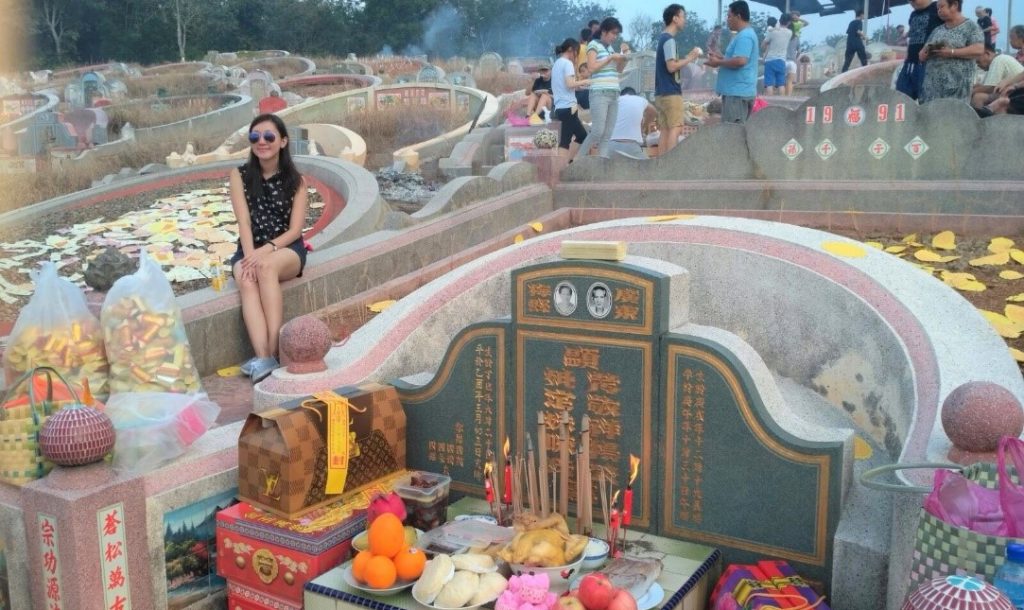

At my grandparents’ grave, with much food and paper offerings laid out for the festival.

At my grandparents’ grave, I reflect on how their lives are intertwined with wider sociocultural histories and customs. I observe the Chinese idioms and paintings adorning the grave, and the rituals associated with the festival: the tidying of the graves, the laying out of sumptuous food offerings (some of which is “recycled” for our lunch later), the paying of respects with joss sticks, and the burning of paper offerings. I think about my grandparents’ ties to China when looking at the inscription of their Chinese hometown on the headstone.

Today, the histories and memories that come to mind are also more of a personal nature. The festival effects a temporal change in this landscape of death, which comes alive with ties of kinship. My extended family catches up with one another, and I also watch as up to four generations of families come together, and scenes such as a pair of elderly men slowly but steadily clearing the unkempt vegetation off a grave. The atmosphere is festive, as families gather around the graves to assist with the tasks of tidying the graves, setting out the offerings, and to chat. Ears are covered and conversations are periodically interrupted by the explosive, crackling sounds of firecrackers puncturing the air.

A ‘landscape of death’ coming alive as families gather during the Qing Ming Festival. Burning paper offerings of money, clothes, or even ‘branded’ bags for the departed Setting off firecrackers on my grandparents’ grave

While the Qing Ming Festival associated with ancestor worship, its meaning to me lies more in the realm of the mundane. I recall the warm family dinners with my grandparents. As I exchange greetings with my relatives, I realise that apart from Chinese New Year, this is the only other occasion the extended family gathers. Family gatherings used to revolve around my grandparents and I am glad that through the Qing Ming Festival, my grandparents, and our memories of them, take centre-stage in bringing the family together once again.

Ming Li Yong is a Geographer at the University of Sydney, for more on her work and research you can follow her on twitter or read more of her work here.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss