In the second article of a two-part series, Andrew Selth takes a look at superheroes and more in Myanmar comics.

Over the past 75 years, Western comic books with a Burma theme have been dominated by stories set during World War II. There were some noteworthy exceptions but, even when new characters appeared and the plots changed, descriptions of the country and its population rarely did so.

During the Cold War, Western governments exploited the power of comics to influence public opinion, including in Burma. For example, in 1950 the British embassy in Rangoon persuaded a local newspaper to run a comic strip based on George Orwell’s anti-totalitarian fable Animal Farm. In 1961, the US government recruited Roy Crane, creator of the comic book hero Buzz Sawyer, to help save countries like Burma from communism. In a series entitled ‘Your United Nations at Work’, a 1963 Action Comics story portrayed a young Burmese woman who saved her village, thanks to her training at a WHO school in Rangoon. While described as part of a public service program, such stories were designed to garner support for the then pro-Western UN.

Burma also continued to provide the setting for adventures by a range of heroes, heroines and superheroes.

Between 1942 and 1953, for example, Fawcett Comics published a series called ‘Nyoka the Jungle Girl’. It was based on a film serial inspired in turn by a 1931 pulp fiction story by Edgar Rice Burroughs, about a Cambodian princess. The later Nyoka character lived in Africa, but this did not prevent her from appearing in two multi-part stories set in Burma. ‘The Burmese Expedition’ was released in 1947, followed by ‘Adventure in Burma’ in 1948. In these stories, the smartly-dressed Nyoka frequently encountered wild animals, with mixed results, and in one tale had to deal with a ‘Chinese head hunter’.

In 1961, DC Comics published a story in its ‘Greatest Adventure’ series entitled ‘I was the Burma Tiger-Man’, about a shape-shifting white hunter determined to track down and kill a man-eater terrorising the local villagers. From the illustrations, which depicted turbaned ‘natives’ and large stone Mughal-style buildings, readers might be forgiven for thinking that the action took place in India. However, the story relied on the usual Orientalist tropes (thick jungle, wild animals, cave-dwelling hermits, magic potions and so on) to paint a picture of Burma that was both exotic and exciting.

Burma is mentioned in a few Superboy and Superman comics, usually only in passing. However, in ‘The Secret of the Superman Stamp’ (DC Comics, 1962) a story is devoted to the Man of Steel’s efforts to prevent a photograph of himself being used on a Burmese postage stamp, which was proposed after Superman saved the country’s capital from a geyser. His concern was that, if stamps carrying this photo were postmarked in Rangoon, the ‘oo’ in the city’s name could appear over his eyes, giving the impression that he was wearing glasses, and revealing his secret identity as the bespectacled reporter Clark Kent.

Wonder Woman also knew something about Burma, although she never went there. In a 1975 comic, she visited a US circus to stop the Burmese elephant trainers from killing their animals out of a superstitious belief that ‘foreign devils’ were hurting their ancestors’ souls. WW discovered that they were being duped by a Japanese spy in order to sabotage the circus’s support for the US defence forces. In an even more far-fetched story published in 1985, in which the Amazons and the gods join forces to foil an alien invasion of Earth, the ex-lover of an arms-trafficking US general hails from Burma.

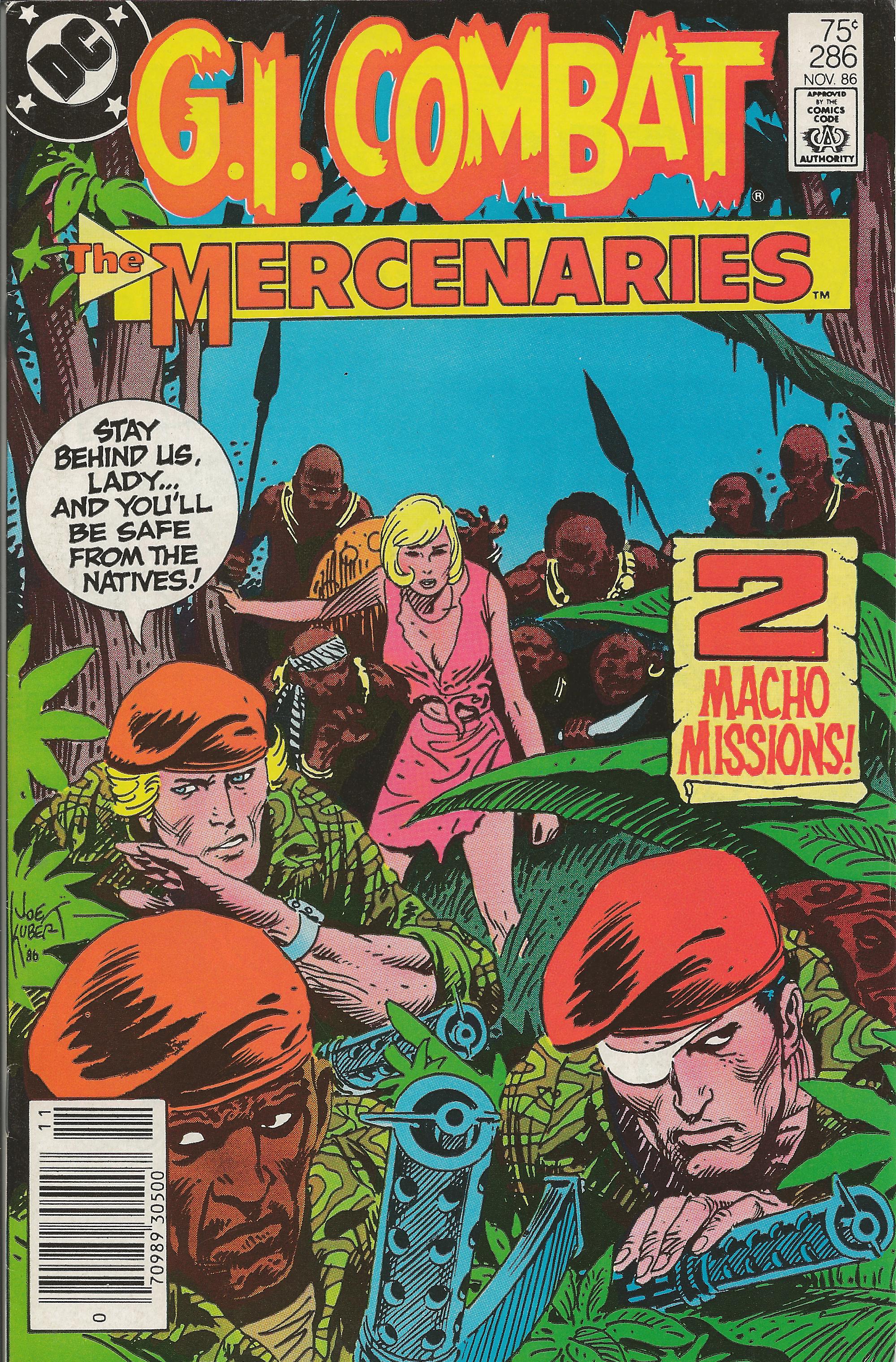

In 1986, a story in the G.I. Combat comic series was entitled ‘Dead Winner’. It described a group of mercenaries who, in an attempt to evade the police in the Bay of Bengal, accidentally sailed up the Chindwin River — somehow skipping 600 kilometres of the Irrawaddy River! In a bizarre mix of literary clichés with both Asian and African overtones, there was a missionary sick with fever, a faithful retainer, a damsel in distress, ‘treacherous jungle’, poisonous snakes, ‘native drums’, witch doctors in feathered headdresses and spear-wielding head hunters. It all made for great entertainment, but bore little relation to the real Burma.

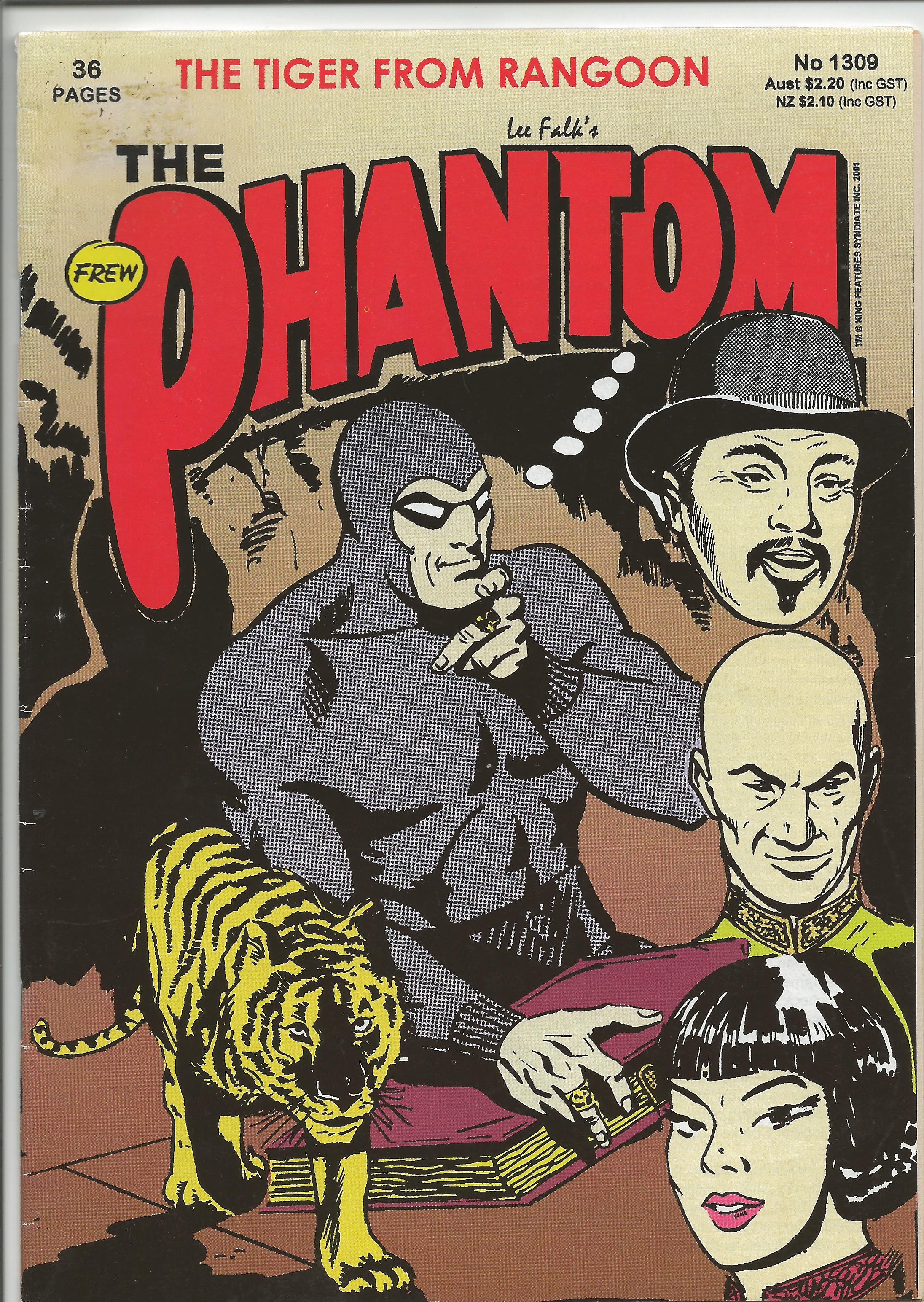

The Phantom appears to have gone to Burma at least twice. In ‘The Phantom Goes to War’ (1950-1) the Ghost Who Walks took on the Imperial Japanese Army (for the land of ‘Bengali’, read Burma). In ‘The Tiger from Rangoon’ (1974), he foiled a Chinese secret society smuggling Burmese heroin. In ‘The Search for Byron’ (1996), the Phantom went to southern Burma to rescue a missing aviator from head hunters. He revealed that he had been there before, helping to sort out ‘a nasty tribal war’. He felt that Burma was ‘a terrible country … wild animals, thick jungle, incredible heat, ferocious natives’.

More recent comic books refer to Burma (as it was still called, even after its name was changed in 1989 to Myanmar) much less frequently. However, when it is mentioned, it is in familiar terms.

In 2000, for example, the ‘Marvel Knights’ (including Daredevil, Dagger and the Black Widow) were attacked by Zaran the Weapons Master and Fu Manchu. The Chinese arch-villain sent men from ‘Burma’s dacoit assassin cult’ to the US to destroy the superhero team. In a 2008 story, superhero Bei Bang-wen (aka Iron Fist) and his Indian counterpart Vivatma Visvajit went to Burma to free Bahadur Shah Zafar, India’s ‘poet emperor’, who was exiled to Rangoon by the British after the 1857 Indian Mutiny. In 2014, the 1944 Blazing Comics hero Green Turtle and his side-kick Burma Boy attempted a comeback.

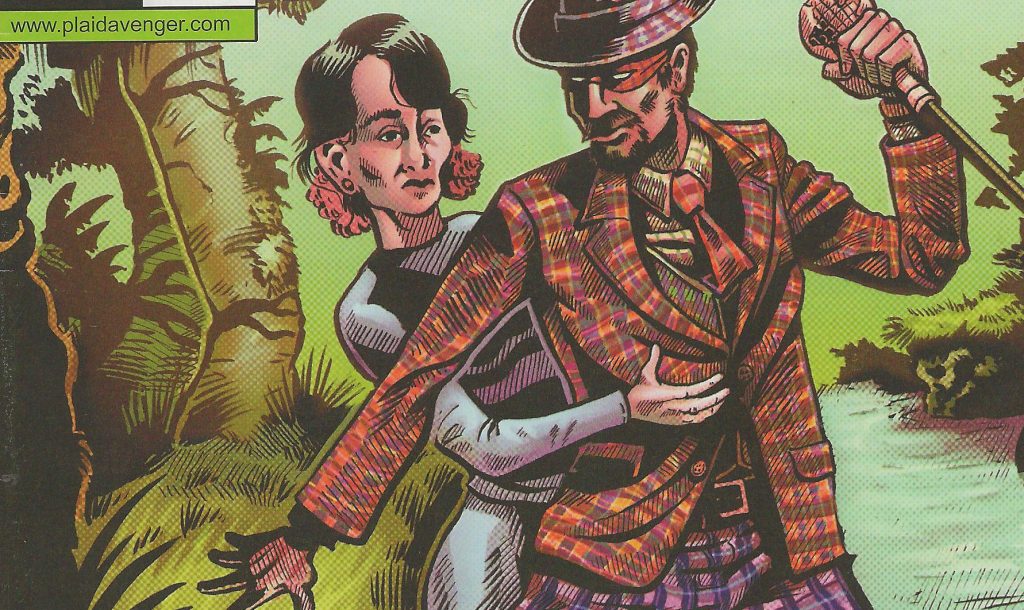

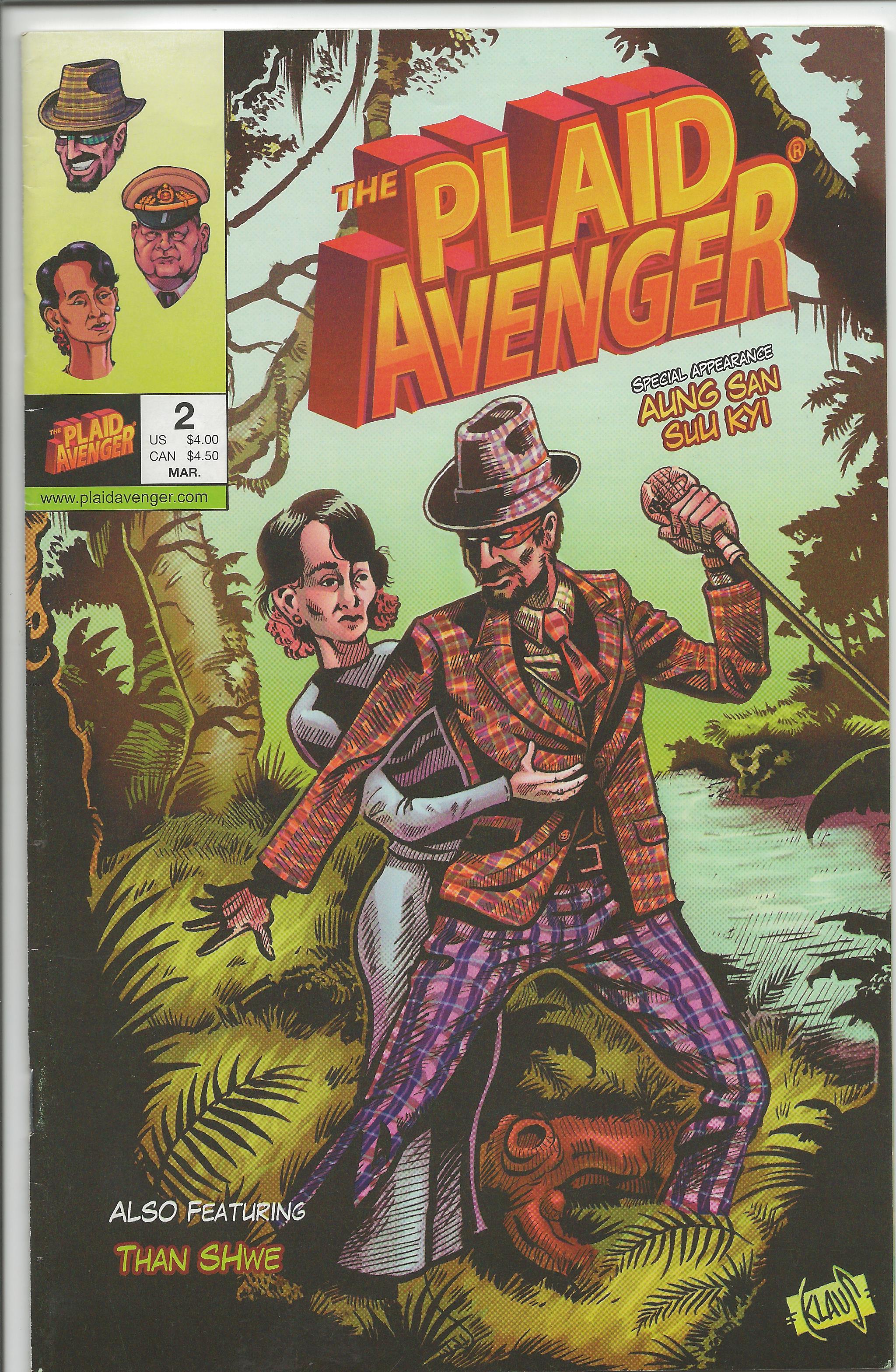

In 2010, an American ‘action docu-comic’ attempted to throw light on contemporary Burma. The lead character was The Plaid Avenger, described as ‘a lone fighter for truth, justice and the international way’ who ‘roams the planet to fight international injustices’. The comic’s stated aim was to educate readers about ‘the real-world facts behind the real-world situations the Avenger finds himself in’. While it made a strong case against Burma’s then military government, the accompanying story about his attempt to rescue Aung San Suu Kyi was riddled with factual inaccuracies and tendentious claims.

Despite these examples and many others (one database lists over 300, in several languages), Burma has not played a major role in Western comic tradition. It has served mainly as a colourful backdrop against which Caucasian heroes and heroines can perform feats of derring-do, resolve personal crises or act out dramas on the world stage. In most instances it owes its appearance to World War II when Burma became better known, albeit in stereotypical terms, to Western populations. Emphasis has been given to its remoteness, striking geography, lack of development and ability to test the limits of human endurance. Inevitably, there have also been fantastical elements.

Two additional points need to be made.

The first is that Burma itself has a strong tradition of cartoons and comic strips, dating back as far as 1912. They have been powerful vehicles for political expression, social commentary and popular amusement. The first modern Burmese language comic book was published in 1960, and for the next three decades such publications were a major source of entertainment for young Burmese. Secondly, it is worth noting that since the 1990s several ‘graphic books’ about Burma have become available on the world market. Four quite different examples of the genre are Hot Nights in Rangoon (1997), Burma Chronicles (2007), Darkie’s Mob (2011) and Mandalay (2015).

From time to time, there have been accusations that comics corrupt the young and encourage anti-social or even criminal behaviour. During the 1950s, codes and laws were introduced in the UK and US to regulate the violence and horror (but not the sexism and racism) found in many comic books. Also, efforts were made to produce publications like Eagle (1950-69) that featured more wholesome characters and uplifting stories. Despite the moral panic of those years, no hard evidence has ever been presented to substantiate the claims of the critics. However, it is now widely accepted that comics have had, and continue to have, a significant impact on the public imagination.

The most enduring mental pictures of a country are formed not from a single source, but from the combination of many often subtle influences, accumulated over time. The popular perceptions of Burma formed in the West last century derived in part from literature, and any consideration of this category must include comic books. For, despite their lowly status and often ephemeral nature, they were powerful social documents which portrayed Burma and the Burmese people in ways that were bound to be absorbed by many young readers, to become part of their imaginative inner world.

Andrew Selth is Adjunct Associate Professor at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University, and at the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, Australian National University.

This article is the second in a two-part series on comics in Burma. Read part one on wars and rumors of wars here.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss