Opening just a week after the anniversary of the 2021 military coup in Myanmar, Fighting Fear II: It Goes Without Saying showcases the work of nine Burmese artists in the intimate space of a home gallery in Newtown—16albermarle. It is a sequel to the 2021 exhibition, Fighting Fear: #whatshappeninginmyanmar, curated by Nathalie Johnston and Sid Kaung Sett Lin, directors of Yangon-based Myanm/art project space. Those who are familiar with the former exhibition may recall a fiercely irreverent show of posters saturated in revolutionary hues of red, a colour which had been banned from use by the government. Two years down the track, Nathalie and Sid present the second instalment of Fighting Fear, which shifts in shape and mood.

Since our last encounter, lives have stirred, some displaced. In a sense, the exhibition is a much-needed update. We learn that many artists have fled the country, while others have found sanctuary in the outer fringes of the state, and a couple have remained. The time elapsed and the distance traversed is palpable in the artistic practices on display. The immediacy of the images of protest now give way to stories of remembrance, resilience, and survival, many told from afar. Fighting Fear II reminds us that revolution is also carried out and continued in the granular aspects and motions of the everyday.

Emily Phyo, for example, shares photographs documenting her escape from Myanmar via the Thai border to Austin, Texas in the United States. Selected works from the final few posts of Emily’s social media project #Response365 (2021–22) are placed alongside a more recent set of photographs marking the beginning of #BeingEmily (2023–ongoing). Despite the rather distinct shift from tightly framed portraits featuring the three-finger salute to tender vignettes of ordinary life which blur in and out of focus, many of the photographs across the two projects were taken in the span of a few days. It is perhaps not so much indicative of an abrupt change in focus, but instead a recasting of perspective.

A reply from Yangon is found in Soe Yu Nwe’s photographs and screenshots of Instagram posts, which accompany her drawings responding to the coup in 2021. They capture moments of delight, frustration, fear, and confusion. We glimpse hands at work in Soe’s clay art studio, Studio Nwe, and low-quality images of flooded streets and traffic. A calico cat sleeps serenely in one picture, and another contains nothing but despairing observations of rising living costs, electricity shortages, and widespread crime. There is something oddly familiar and strikingly authentic about these cell phone pictures which hang in the hallway—it is as if they could appear at any time on our Instagram feeds—that eats away at the perceived gap between artist and viewer, between Sydney and Yangon.

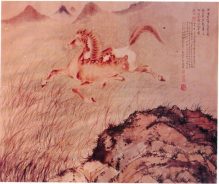

Image: Kaung Su, Untitled #4 2022, inkjet print of Ilford Galerie Smooth Pearl photo paper, 38.5 x 50 cm

This impulse to document connects the works in the exhibition. Min Ma Naing compiles and pastiches together photographs taken in the immediate aftermath of the coup in 2021 to form anonymous portraits of protestors in Faces of Change. The quotations collected from ad hoc interviews replace conventional wall texts, sustaining the life of the work as an ongoing process of piecing together, revisiting, and relaying stories and memories. And yet anger and grief does not dissipate. Red sullies Kaung Su’s Red Paint Series (2022) which documents the red paint protests of April 2021. Almost corrosively, the pigment stains the cityscape, seeping into the cracks in tiled sidewalks, thrown forcefully against barricades and roadside curbs. It conjures images of bloodshed and loss—a tension between presence and violent absence which punctures the photographic surface.

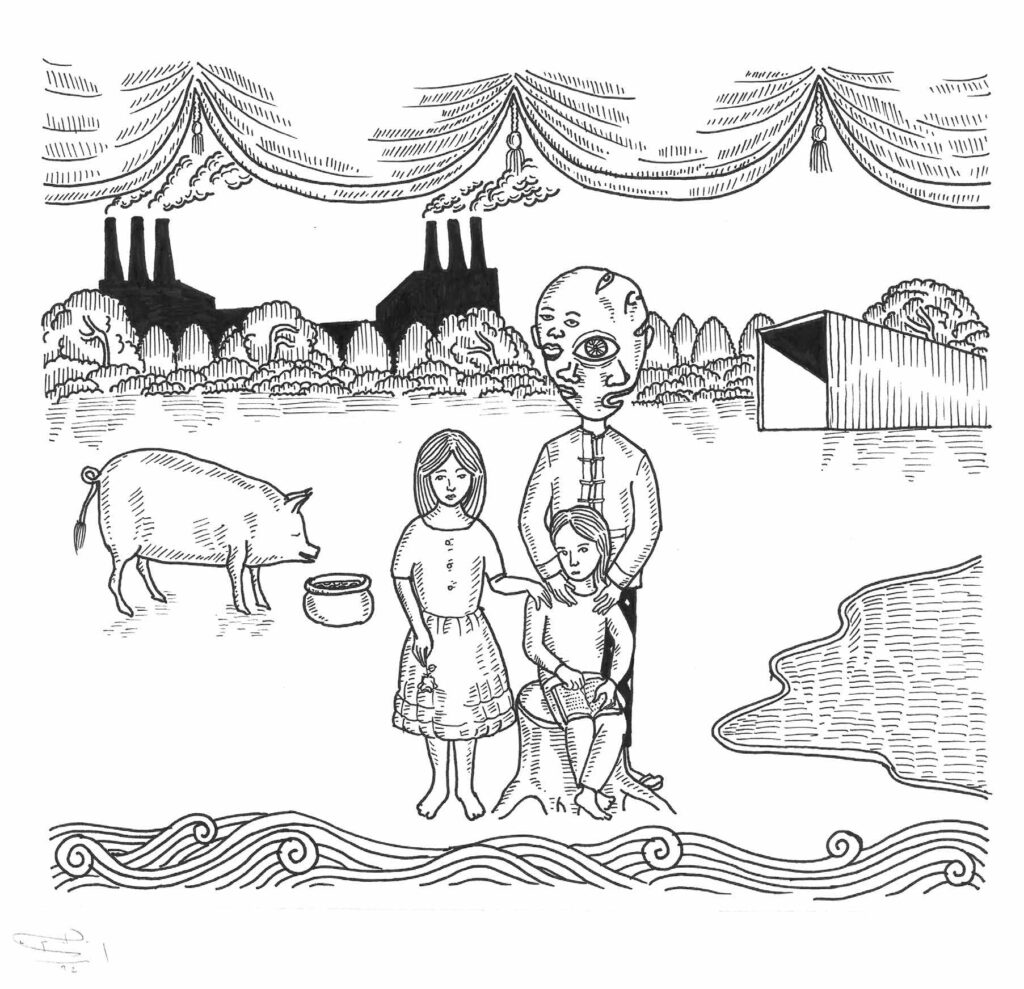

Image: Maung Day, Lost Children 3 2022, inkjet print on matte poster paper, 21 x 29.7 cm

The prominence of the photograph in Fighting Fear II, however, does not totally overshadow the array of artistic media on display. Maung Day’s small and seemingly light-hearted etchings contain and bear monumental tragedies, accompanied by sombre poems which mourn a generation lost to and haunted by years of political turmoil and violence. Bart Was Not Here’s (Kyaw Moe Khine) vivid and stylised illustrations amalgamate intertextual references and imagery to serve provocative critiques of the military regime while Richie Nath renders his haunting tribute to victims of the mass burning and looting of Rohingya villages in oils, gouache, and ink.

Image: 882021, Generational Curse 2022, inkjet print on matte poster paper, 120 x 120 cm

Next to the stairwell is the largest singular print on show, made specifically for the exhibition. The artist takes the pseudonym 882021, referencing both the hex colour #882021—a deep maroon resembling aged blood—and nationwide protests which broke out in 1988 and again in 2021. 882021’s interest in the cyclical pattern of political disturbance and trauma in Burmese history translates to his illustration of a Saṃsāra in Generational Curse. It is simultaneously a picture of suffering and an expression of hope; 882021’s invocation of the Saṃsāra intimates eventual emancipation.

Besides their interlapping themes and motives, gallery visitors may notice another commonality uniting the works on display. It is an exhibition (almost) entirely constituted of inkjet prints, with the exception of Soe’s two drawings, which were first shown as prints in 2021. This is no accident, nor is it a case of cutting corners, but rather an essential requirement. Urgency and necessity are embedded in the medium itself and the ways in which it lends itself to reproduction and dissemination. All works of art were originally assembled at Myanm/art, Yangon by the curators and artists, and then sent, downloaded, printed, and editioned in Sydney. The choice of medium is a method of survival.

Uncovering transnational and gendered experiences reveals a far richer and more multifaceted picture of Indonesian art and identity.

Forgotten art history: the art of Chinese-Indonesian women in the 20th century

My final point of praise is the exhibition’s inseverable connection to the now—a keenness and quickness to respond to real-time events that is often quashed by the slow-turning wheel of academia and institutions. Over the course of the exhibition’s six-and-a-half week run, 16albermarle hosted a series of public programs which offered up the project space to Sydney’s Burmese community. On 4 March audiences were invited to a conversation between Burmese-Australian activist Mon Zin and the Executive Officer for Union Aid Abroad-APHEDA Kate Lee, moderated by Sydney University’s Dr Susan Banki. At the exhibition’s opening, filmmaker The Khit Nay spoke to the vitality of artists in the revolution as image-makers and documentarians of resistance—as those who are the last to be acknowledged in times of political stability and the first to be persecuted in political turmoil. He is joined by cultural worker Khin Thu Thu who translates for the audience and urges for the continued support of the artists. A nearby table is generously filled with plates of lahpet thoke (fermented tea leaf salad) and other delicious foods, prepared and served by Ma Ei Nu, the owner of a grocery store called Golden Mandalay in Auburn. As we eat, talk, listen, and look, we are reminded that questions of how to protest invariably give rise to questions of how to stand in solidarity.

Fighting Fear II: It Goes Without Saying was a fundraising exhibition shown at 16albermarle in Newtown from 8 February 2023 until 25 March 2023. Artworks can be purchased on a print-by-demand basis and all proceeds will be remitted to artists after deducting print costs.

The next exhibition at 16albermarle Project Space will be Ghosts from the Past by Indonesian artists Enka Komariah & Ipeh Nur, running 15 April–20 May 2023.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss