As President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s decade in office comes to an end, the President remains a well-regarded figure by much of the international community – even though both presidential candidates seek to distance themselves from his perceived weak and vacillating leadership.

Last month SBY became the third person ever to be awarded the title of Global Statesman by the World Economic Forum on East Asia. The international media largely applauded SBY for propelling Indonesia ‘from being among Asia’s lowest-regarded states in the early part of last decade to a darling of the international community.’

It is without doubt that SBY has overseen a transformation of how Indonesia is perceived by the outside world, a result that can be significantly attributed to his own promotion. The President has provided a blueprint for an internationalist foreign policy that his successor would be wise to build upon.

When SBY assumed office in 2004 after winning the nation’s first directly elected presidential election, Indonesia was faced with weak economic growth coming out of the Asian Financial Crisis, a yet to be consolidated democratic transformation and waves of secessionist and terrorist violence; little to enthuse international partners and investors. The last 10 years have presented to the world an Indonesia stronger on all fronts; the economy is growing at a healthy rate, being upgraded to investment grade in 2011 from the junk status it held since the crisis; democracy has been consolidated, even if further progress has been lacking; and peace has been made in Aceh, with terrorist cells largely uprooted and destroyed.

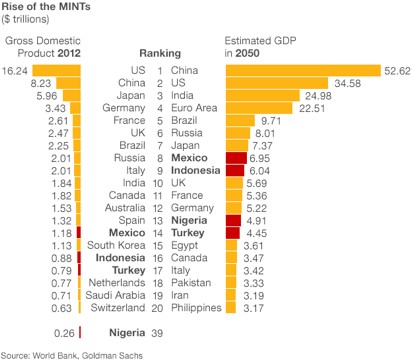

Today’s Indonesia bathes in a sea of global by acronyms, all pointing to its strength and heralding its positive future: CIVETS, EAGLE, TIMBIs, the N-11, the 3G and more recently as a member of the MINTs (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, Turkey) by Jim O’Neill of BRICs fame.

Under SBY’s watch Indonesia became a member of the G20, was instrumental in forming the East Asia Summit and created the Bali Democracy Forum, a favourite among authoritarian governments for being ‘about democracy, not of democracies’.

SBY has been far from passive in promoting Indonesia on the international stage; the US-educated, English-speaking, former general has been a regular at global summits. He has been active in the G20, as well as the World Economic Forum, was awarded the World Statesman Award in 2013 for ‘promoting tolerance and respect for human rights’ (in international affairs, often perception is more important than reality), received the Order of Australia for his role in fighting terrorism, promoting democracy and strengthening regional groupings, and more recently was named to be a co-chair of the UN’s ‘post-2015 development agenda’ commission. During his decade in office Indonesia has hosted the Asian-African Conference in 2005, the UN Climate Conference in 2007, chaired ASEAN in 2011 and APEC in 2013. SBY’s address to the Australian Parliament in 2010 was credited with improving the Australian public’s perception of Indonesia; it became favorable for the first time in 2010, a record that has been maintained this year.

SBY and his ministers have promoted Indonesia as the world’s third largest democracy, as well as it’s largest Muslim nation, seeking to carve out a bridging role between the developed and developing world and the Western and Muslim world. As a champion of the developing world, SBY has received favorable comparisons to charismatic and internationally well-regarded former Brazilian President Luiz In├бcio Lula da Silva. As a champion of the Muslim world, he has endeavored to act as a mediator in the wake of the Danish cartoon controversy and called for an anti-blasphemy law to be adopted by the UN in 2012. Adopting a foreign policy of ‘a million friends and zero enemies’, the President has seen relations with practically all countries improve. Over his ten years in office Indonesia has signed strategic partnerships with countries including: Australia, Brazil, China, India, Japan, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey and the United States. It is little surprise then that President Yudhoyono was named one of the top 100 leaders & revolutionaries by influential American magazine, Time, in 2009.

In stark contrast to SBY, this election’s two presidential contenders – former-Kopassus Commander Prabowo Subianto and Jakarta Governor Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo – both appear less capable and less likely to follow SBY in promoting Indonesia on the world stage.

Prabowo, while having spent considerable periods of his life overseas (either as a result of his economist father’s role in the late-1950s ‘Outer Islands’ rebellions or his self-imposed exile to Jordan in the late-1990s) and being a well-regarded orator with a fluency in English (a point taken up in a rather low-brow piece by Prabowo-supporter Aburizal Bakrie’s TVOne), is beleaguered by accusation of human rights abuses. These are sure to make relations with Western democracies somewhat problematic; Prabowo was denied a visa to enter the US for his son’s university graduation in 2000 and again in 2012. Although, the recent election of Narendra Modi and the revocation of his former ban reveals that the US, and the West more broadly, will act pragmatically in the case of a Prabowo presidency. In fact, the US Ambassador to Jakarta has already indicated that the ban will be lifted if Prabowo wins the 9 July election.

The vision and mission statement offered by Prabowo-Hatta spurns details and we are left with little more than platitudes. However, under a Prabowo presidency we would expect a more assertive and nationalistic Indonesia, something that Prabowo has been calling from since at least his 2012 speech in Singapore.

Jokowi, on the other hand, has little to no international affairs experience, is comparably less comfortable with English and has an oratory style which has been a constant source of criticism. The Jakarta Governor did make an attempt at bolstering his foreign affairs credentials late last year, hosting a meeting of governors/mayors of the ASEAN capitals, in which he purposely gave a speech in English.

Perhaps recongnising these weaknesses, talk has it that Jokowi’s more detailed foreign policy platform as set out in the Jokowi-JK vision and mission statement, was formulated under the guidance of well-known academic Dr Rizal Sukma, a Muhammadiyah figure and prominent ASEAN critic. With Sukma as an advisor and, a potential Minister for Foreign Affairs in a Jokowi administration, Jokowi’s Indonesia would be tempted to take a more independently minded stance on international questions.

Neither of these two men are as inclined as SBY to focus on international diplomacy or have the necessary skill sets that formed the foundation of SBY’s success. With his final term coming to an end in October, many in the international community will surely miss SBY’s presence on the world stage.

While Indonesians may look back fondly on the Thinking General’s promotion of their nation, if Indonesia’s international stature takes a tumble in the throes of a more-nationalistically inclined Prabowo or Jokowi presidency.

David Willis is a PhD candidate at the School of International Studies at Flinders University. He is currently researching the role of domestic politics in Indonesia’s foreign policy.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss