“Is Malaysia a secular or Islamic state?”

Without a doubt, this is one of the most frequently asked questions in Malaysian politics. It is also one of the most polarising and misleading questions in Malaysian politics. This is because the question itself tends accept certain premises of the government’s claim to speak for Islamic law.

In my recent article, “Judging in God’s Name,” I argue that Malaysia is not an Islamic state, but not for the reasons that are usually offered by secular, liberal rights activists. Secular activists typically look to the Federal Constitution or cite the documents of the Reid Commission to establish the secular foundations of the Malaysian state. While these sorts of arguments may be well founded, I argue that their impact will be limited if the government’s claim to implement ‘Islamic law’ is not challenged more directly.

Although Malaysia ranks sixth out of 175 countries worldwide in the degree of state regulation of religion, this should not be understood as the implementation of an “Islamic” system of governance or the achievement of an “Islamic state.” No such ideal-type exists.[1] Instead, Malaysia provides a textbook example of how core principles in the Islamic legal tradition are subverted the moment that a government claims an absolute monopoly on religious authority. The very question, “Is Malaysia a secular or Islamic state?” obscures this fact. In what follows, I provide a brief overview of the argument.

The Islamic legal tradition

The absence of a centralised authority is one of the defining features of Islam. Through the first several centuries of Islam, a pluralistic legal order emerged with dozens of distinct schools of interpretation, each with its own methods for engaging the Qur’an and other textual sources of authority. Within each school of interpretation, private legal scholars operated within a rigorous interpretive framework to perform ijtihad (the effort to discern God’s way) by issuing fatwas, non-binding legal opinions.

Diversity of opinion among jurists (ikhtilaf) was not understood as a problem. On the contrary, difference of opinion was embraced as both inevitable and ultimately generative in the search for God’s truth. Adages among scholars underlined this ethos, such as the proverb, ‘In juristic disagreement there lies a divine blessing.’ In both theory and practice, Islamic law developed as a pluralist legal system to its very core. More to the point, human understanding of God’s will was recognised as unavoidably fallible, and because of this, religious authority was not considered absolute. A fatwa was simply the informed legal opinion of a fallible scholar; it was not considered an infallible statement about the will of God.

Contrast this with how the Malaysian government has manipulated the Islamic legal tradition. The government replaced the tremendous diversity in religious interpretation with a codified version of state-enforced “Islamic law.” Government-appointed Muftis are empowered to issue fatwas that are “binding on every Muslim resident.” Fatwas carry the force of law and are backed by the full power of the Malaysian state. The Syariah Criminal Offences Act and parallel state-level enactments further consolidate this monopoly on religious interpretation. Article 9 criminalises defiance of religious authorities. Article 12 criminalises the communication of an opinion or view contrary to a fatwa. Article 13 criminalises the possession materials that contain views contrary to edicts issued by religious authorities. In sum, state officials command a complete legal monopoly over religious interpretation.

Naming as a means of claiming Islamic law

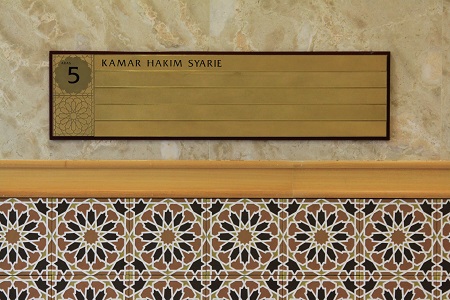

In spite of this authoritarian reformulation of the Islamic legal tradition, there was an important shift in the way that “Islamic law” was presented to the Malaysian public beginning in the 1970s. The 1957 Federal Constitution had outlined a limited role for the states to administer “Muslim law.” But a constitutional amendment in 1976 replaced every mention of “Muslim law” with “Islamic law.” Likewise, every mention of “Muslim courts” was amended to read “Syariah courts.” The change in wording soon appeared in statutory law: the Muslim Family Law Act became the Islamic Family Law Act; the Administration of Muslim Law Act became the Administration of Islamic Law Act; the Muslim Criminal Law Offenses Act became the Syariah Criminal Offenses Act; the Muslim Criminal Procedure Act became the Syariah Criminal Procedure Act, and so on.

Why is this important? In all of these changes, the shift in terminology exchanged the object of the law (Muslims) for the supposed essence of the law (as ‘Islamic’). This is a prime example of what Erik Hobsbawm calls “the invention of tradition.” The authenticity of the Malaysian “syariah” courts is premised on fidelity to the Islamic legal tradition. Yet, ironically, the Malaysian government reconstituted Islamic law in ways that are better understood as a subversion of the Islamic legal tradition. Every reference to state “fatwas” or the “syariah courts” serves to strengthen the state’s claim to embrace the Islamic legal tradition. Indeed, the power of this semantic construction is made clear by the fact that even in a critique such as this, the author finds is difficult to avoid using these symbolically laden terms. It is with the aid of such semantic shifts that the government presents the syariah courts as a faithful rendering of the Islamic legal tradition, rather than as a subversion of that tradition.

The Islamic state debate is misleading because it directs attention away from the fact that a completely new, authoritarian legal form has been created with only tentative connections to the Islamic legal tradition. Ironically, the government’s claim to religious authority rests upon the subversion of the very tradition that it claims to establish.

Liberal rights activists will continue to encounter great difficulty in confronting the rhetoric of conservative NGOs, UMNO, PAS, and the “Islamic” bureaucracy without directly challenging and disarming monopolistic claims to Islamic law. Ironically, this requires liberal rights activists to engage in religious argumentation, or at least to work closely with groups such as Sisters in Islam and the Islamic Renaissance Front, which challenge the government’s claim to “Islamic law” through the framework of the Islamic legal tradition itself.

For the full academic article from which these bits were taken, see “Judging in God’s Name: State Power, Secularism, and the Politics of Islamic Law in Malaysia” in the Oxford Journal of Law and Religion, vol. 3 (2014) 152-167.

[1] A number of scholars have advanced different versions of this argument, from the prominent Egyptian shariah court judge and al-Azhar scholar ‘Ali ‘Abd al-Raziq in 1920s Egypt to recent academic work by Sherman Jackson, Abdullahi an-Na‘im, Wael Hallaq, and others. See Sherman Jackson, Islamic Law and the State, Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na‘im, Islam and the Secular State, and Wael Hallaq, The Impossible State. Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss