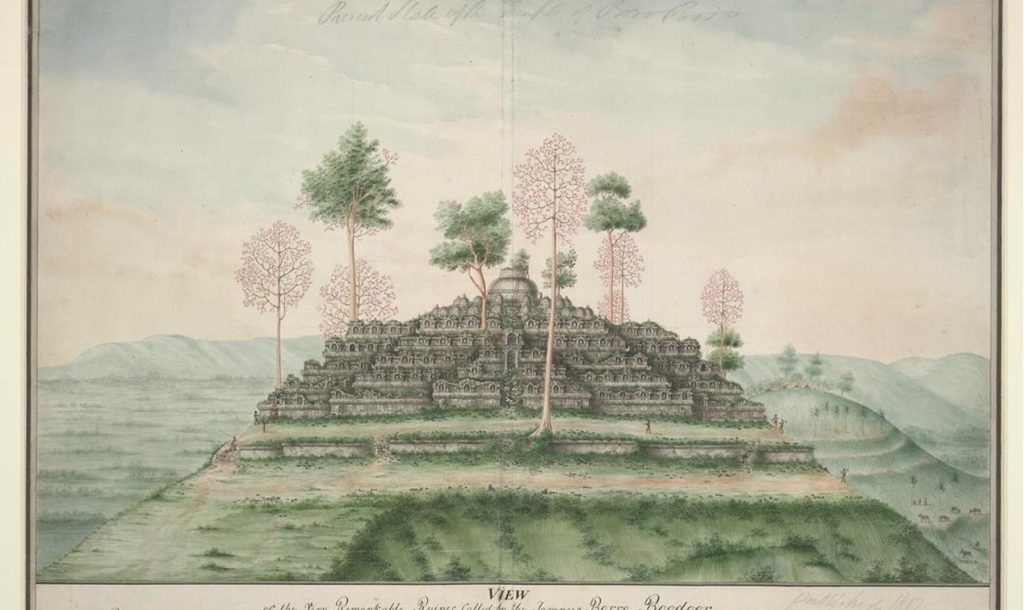

In August 2014, I helped organise a national seminar in Magelang, Central Java, that celebrated the 200th anniversary of the supposed “discovery” of the temple of Borobudur by the then British lieutenant governor-general of Java, Sir Stamford Raffles. Archaeologists, historians, and conservation experts convened to discuss what could be done to preserve Borobudur for another 200 years. Later that year, and still in the spirit of this celebration, the Indonesian Postal Service issued 20,000 unique postage stamps showing the Borobudur temple foregrounded by a painted portrait of Raffles. The stamp design was officially launched in the courtyard of Borobudur by Puan Maharani, then Coordinating Minister for Advancements of Human and Culture, accompanied by Rebecca Razavi, the British Consul General to Indonesia and Timor Leste, and Ganjar Pranowo, then the governor of Central Java.

Read any historical book on Borobudur today, and you will most certainly find this narrative of “discovery”. But while adoration for Raffles prevails, it is remarkable that—contrary to what is depicted on those 20,000 stamps—he did not personally go to see the temple in 1814. He was indeed the first European scholar to describe the ancient site in his widely recognised 1817 book, The History of Java, recently translated and re-published in Indonesian language. But this account was based on reports and drawings from the Dutch engineer Hermanus Christiaan Cornelius, whom Raffles had assigned to survey the area following a tip-off from an unnamed local official. Moreover, the description of the Javanese temples in his book fixated on the notion that Hindu and Buddhist monuments had been abandoned and lost their meanings following Javanese conversion to Islam in the early 16th century—a contested colonial narrative that continues to reverberate in Indonesian archaeology and heritage-making today.

But Raffles’s book was thankfully not the only text produced in this period to contain accounts of the ancient Javanese temples and their later significance. The 1815 manuscript Centhini Kadipaten—an exceptional version of a Javanese text broadly known as the Serat Centhini—provides dramatised accounts of visits by Javanese santri (students of Islam) to a handful of Hindu and Buddhist temples across Java during the reign of Sultan Agung of Mataram (1613–1645). Its 12 volumes and 3,500 stanzas compile and retell accounts from older court manuscripts dating back as far as 1616, interlaced with stories borrowed from other Javanese texts and oral traditions beyond the court’s walls. The Centhini Kadipaten manuscript contests the dominant colonial narratives of “abandonment” and “discovery”—and a close reading of its contents tells a different story altogether about the shifting values of ancient Javanese temples.

The colonial gaze in the archaeology of Indonesia

Authorised heritage-making for ancient sites in Indonesia often gravitates towards memorialisation of colonial narratives. In part, this has been driven by the colonial assumption of rupture in localised attitudes towards ancient monuments in Java following conversion to Islam. This assumption can be traced back to Raffles. In his own words:

The natives are still devotedly attached to their ancient institutions, and though they have long ceased to respect the temples and idols of a former worship, they still retain a high respect for the laws, usages, and national observances before the introduction of Mohametanism. [Emphasis added]

“Idols” here connotes figural representations, or statues, of gods from Hindu and Buddhist traditions, such as the tiered complex of Buddha statues at Borobudur.

Another example can be found in Penataran, a Javanese Hindu temple built in the 12th century, which is also said to have been “discovered” by Raffles in 1815 after a long period of purported neglect. This false yet pervasive impression of “abandonment” was manufactured by colonial scholars such as Raffles by ignoring Islamic (re)production of knowledge and (re)appreciation of Hindu and Buddhist monuments. Until today, accounts from local Muslim communities, particularly those recorded in early modern texts, have never been appropriately acknowledged and considered in the official historiography.

Underpinning this particular heritage construction is the field of archaeology (and, to some extent, art history), in which the primary attitude is to privilege a monument’s original functions and meanings at the time of creation. Hindu-Buddhist sites and materials are then frozen into the period when the local population is thought to have primarily observed them, between the 4th and 15th centuries. Later appropriations in the Islamic context, which may include newly created meanings for these materials, and even those inspired by past values, are mostly deemed ineligible for scientific study within archaeology.

There is a political dimension to why archaeology sustains the colonial framework, seeking to glorify ancient Hindu and Buddhist temples and their original functions. Soekmono, one of the first generation of local archaeologists and known today as the “father” of Indonesian archaeology, was convinced that:

… the period of ancient history also yields a very large number of remains, other than written documents, which are important evidence of the glory of a culture (its architecture), and it is these remains which provide inexhaustible material for archaeology.

This framework helps produce an imagination of past grandeur, especially in the service of history-writing geared towards a particular brand of national identity. Southeast Asian nations tend to engage in archaeology for identity-making by giving prominence to “monumental architecture”. In Indonesia, this architecture includes ancient Hindu and Buddhist temples. Through the process of heritage-isation, these temples are used by the nation-state to celebrate premodern cultural achievements, giving an impression of historical rootedness for the national identity.

Apart from being nurtured along by nationalistic fervour, the framework has also been perpetuated by disciplinary constructions of periodisation and specialisation, with divisions of expertise created along sectarian and chronological lines. This periodisation-cum-specialisation has driven knowledge about broader Javanese cultures to be divided into pre- and post-16th century blocs: Islamic perspectives are exclusively applied in the study of post-16th century materials, while almost never being considered in the study of the pre-16th century Hindu-Buddhist period. Due to this periodisation, rich cultural texts like the Centhini Kadipaten are largely absent from both archaeology and heritage-making for Java’s Hindu-Buddhist monuments.

Islamic stories of Hindu-Buddhist temples

The dramatised narrative of the Centhini Kadipaten manuscript retells the journeys of three descendants of Sunan Giri, one of the “Nine Saints” (Wali Sanga) believed to have introduced Islam across the island of Java, as well as a fourth figure who married into the family. Siblings Jayengresmi, Jayengsari, and Ni Rancangkapti were forced to disperse across Java after Sultan Agung of Mataram attacked their home, the palace of Giri, a theocratic city-state on the northeast coast. From ransacked Giri, Jayengresmi went on his journey and visited the ruined capital of Majapahit, the temples in Panataran, and the remains of the Padjajaran kingdom along the way. Meanwhile, his brother Jayengsari and sister Ni Rancangkapti were told stories about nearby temples while spending their nights in the Dieng plateau in central Java. The fourth figure in the tale, Mas Cebolang, travelled mainly in the southern region of central Java, where he encountered the temples of Borobudur, Mendut and Prambanan. He would later meet and marry Ni Rancangkapti.

The 1815 manuscript relates to a Javanese genre of literature called santri lelana (wandering Islamic student or scholar). The genre generally concerns a santri scholar exploring life outside the court walls in a vague geographical setting while accumulating new knowledge through encounters and debates with other spiritual figures. In a departure from this style, the Centhini Kadipaten is the first manuscript of its kind to give its stories an existent temporal and spatial setting.

It is also the first to include descriptions of Hindu and Buddhist temples in Java. Many scholars have remarked on these descriptions, yet none have considered them important sources for historical and archaeological studies on Hindu and Buddhist temples. This is partly because the narrative is set during the reign of

The destruction of centuries past should focus the region on preparing for Indonesia’s next mega-eruption.

Fragile paradise: Bali and volcanic threats to our region

Time and place details in the Centhini Kadipaten have compelled comparisons to European travel accounts, and so have attracted some scholarly appreciation. Less appreciated is that the manuscript also has much to teach us about the internalisation of local knowledge, and how it is purportedly written to showcase how the distant past of Java should have been recorded and understood. In many ways, the production of the Centhini Kadipaten became a means to perform Javanese identity against the backdrop of socio-political turmoil in early the 19th century. Its production can be understood as a moral and metaphysical defiance, creating a court-endowed Javanese history in response to then ongoing European-driven knowledge production. It was composed during a time of political disorder in Surakarta, Central Java, prompted by a four-way power contestation between the ruler Pakubuwana IV, the crown prince Mangkunegara III, the British authority in Java (led by Raffles), and the Sepoy troops employed by the British, who planned a failed rebellion in 1815. It should be noted that while Surakarta’s court scribes penned the Centhini Kadipaten, the study of Javanese antiquities by British colonial scholars, including publications such as Raffles’ History of Java, was in full swing.

Considered in this context, the Centhini Kadipaten might have a more tangible link with The History of Java than one would imagine. Foregrounding his discussion on Java’s ancient history, Raffles noted that he was indebted to accounts provided by a few local aristocrats, among them the secretary of Pangeran Adipati of Surakerta (Surakarta). It would be safe to assume that Raffles was referring to Kangjeng Gusti Pangeran Adipati Anom Mangkunagara III, a noble of the Surakarta court, and his “secretary”, or court poet at the time, Yasadipura II. According to tradition, Yasadipura II was one of the principal scribes of Centhini Kadipaten, alongside two other poets, Ranggasutrasna and Sastradipura. If this assumption is correct, then one of Raffles’ important sources for his book was actually involved in producing the Centhini Kadipaten.

Curation of knowledge

Reflecting on questions of remembering and forgetting, one specific episode in the Centhini Kadipaten manuscript can serve as a case study: when Jayengresmi visits the candhi (temple) of Penataran in Blitar, East Java. The visit happens after a sojourn in Trowulan, the capital of Majapahit, where Jayengresmi is accompanied by his two santri-servants, Gathak and Gathuk. In the complex of Penataran, the group observes the relief narrating the Ramayana story at the main temple, and the numeral inscription in one of the smaller temples, recognised today as Candi Angka Tahun (literally the Temple of the Year Numeral). This can be found in lines 29–33 of stanza 20 in Centhini Kadipaten, as below in Modern Javanese transcription and English translation:

Lepas lampahnya dumugi, candhi Panataran Blitar, neng ardi Kelud sukune, sela cemeng kang kinarya, ageng ingkang sajuga, wit ngandhap tumekeng pucuk, ingukir ginambar wayang. |

After walking far, they finally arrived at the candhi of Panataran in Blitar, at the foot of Kelud mountain. The candhi was made of black stones, each stone was big, and, from bottom to top, was carved with images from the wayang (shadow puppet play). |

Radyan gya minggah ing candhi, tundha pitu prapteng pucak, udhunira alon-alon, Gathak Gathuk barangkangan, tyas agung tarataban, tekeng ngandhap Gathuk muwus, Gathak mau gambar apa. |

Raden (Jayangresmi) immediately climbed the candhi, seven levels to reach the top, then went down slowly. Gathak and Gathuk crawled, their hearts trembling, and after they arrived at the bottom Gathuk asked, “Gathak, what were those images from before?” |

Kang ingukir pinggir candhi, lunglungan ceplok kembangan, memper wayang buta kethek, Gathuk ing pangiraningwang, gambare Rama tambak, katara ketheke brengkut, candhi alit tininggalan. |

“Those carved at the edge of the candhi, decorated by flower petals, looked like the wayang monkey giant,” Gathuk guessed, “it was a picture of Rama building a dam, as we could see from his monkey army carrying something.” Then there was a small heirloom temple. |

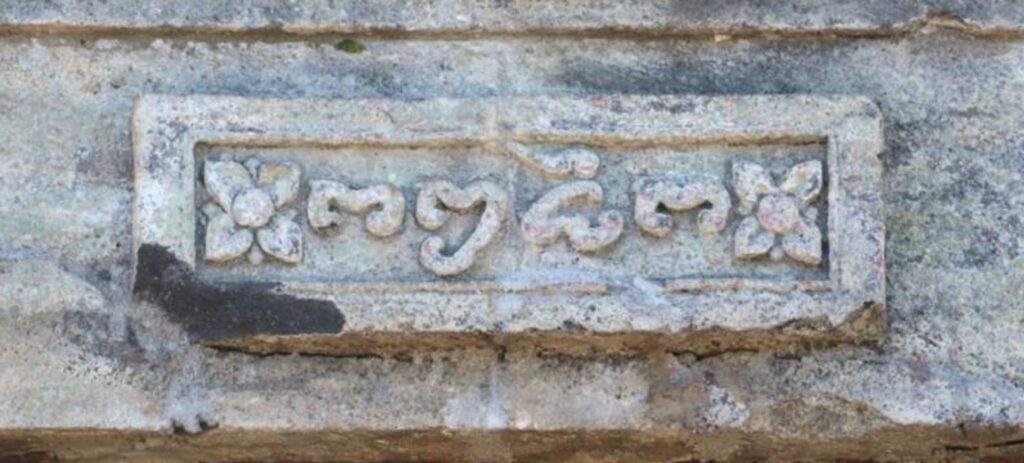

Lir cungkup wangunaneki, ing sanginggiling wiwara, sinerat sastra Budane, Gathuk matur inggih radian, punika kadiparan, kajenge sastra puniku, pating penthalit tan cetha. |

Resembling a grave’s structure, above its entrance door, the script of Buda was inscribed, and Gathuk said, “Please excuse me Raden (Jayangresmi), what is this, this writing here, jumbled and unclear?” |

Rahadyan ngandika aris, sastra Buda papengetan, sewu rongatus etunge, sangang puluh siji warsa, nalikane akarya, ing sanggar pamujan iku, manthuk-manthuk Gathuk Gathak. |

Raden (Jayangresmi) spoke softly, “this Buda script is to commemorate the temple, it is read as one thousand two hundred and ninety one, which is the year when the candhi was made.” In that place of worship, Gathuk and Gathak were nodding. |

The word candhi has been adopted by the Indonesian language (candi) to refer to ancient Hindu and Buddhist temples. It comes from the Old Javanese lexicon, primarily denoting a holy sanctuary where gods descend upon worship. Yet in Modern Javanese, the word can gloss over multiple meanings, including a cemetery, tomb, and mausoleum. In a Javanese–Dutch dictionary published in 1901, candhi is described as “the stones, between and under which the ashes of the burnt corpse of a deceased person were ordered in olden times; a cemetery or mausoleum built over the ashes of a deceased person; a stone temple of ancient times.’’ These meanings may reflect 19th-century Javanese perspectives on the remains of Hindu and Buddhist temples. A closer reading of the word candhi could then reveal how meanings were accumulated over time, with original understandings perhaps at times manifestly forgotten, even while lingering obscurely in the collective memory, which could be recollected and reinterpreted through various forms of knowledge.

Numeral inscription of 1291 of Javanese Era (1369 CE) at Candi Angka Tahun, Penataran. (Photo: author)

Another notable term from the passage above is buda, which generally signifies the distant pre-Islamic past in Java. While derived from the word Buddha, buda typically stood for the hybrid Hindu-Buddhist religion, but also at times included animism in Java. The use of this term in the early 19th century appears to signal the beginning of Javanese fascination with the pre-Islamic past. The term buda then seems to encompass all things that happened before Islam took hold of the Javanese spiritual imagination, starting from the 16th century. The term is notably used in the passage above to refer to the type of script used in the numeral inscription on the temple. We know that the script here is Old Javanese, known as kawi by later Javanese literati. Older texts like Ramayana and Bharatayuddha are written in kawi. Mastery of such texts was considered paramount for court elites to understand Islam in Java, giving one an authoritative voice within the court. This is implied in the passage above when the one who reads aloud the numeral is Jayengresmi, a prince from the theocratic city-state of Giri. We should also note that the numeral “1291” is read correctly, thus debunking the colonial presumption that 19th-century Javanese people could not read Old Javanese inscriptions.

Two panels portraying Rama’s monkey army building a dam, Penataran. Photo by Anandajoti Bhikku (CC BY 2.0)

The passage further reveals that early modern (Islamic) Javanese could understand the stories represented on reliefs in ancient temples. This may be helped by the fact that the Old Javanese Ramayana is one of the pre-16th-century texts to have been copied by the court of Mataram in the second half of the 18th century. At Penataran, it was Gathuk, one of the servants accompanying Jayengresmi, who recognised the panel describing the monkey army’s construction of a water bridge. Considering Gathuk’s lower social status, this episode may reflect the popularity of Rama’s story, frequently retold in public recitals and wayang performance. The connection between the relief and its wayang portrayals is evident in that the figures are portrayed in the carving in the style of shadow puppet figures. While other older tales might have been left forgotten, this continued remembering of Ramayana speaks to early modern Javanese and Islamic curation, in terms of what knowledge from the past is still considered necessary, despite originating from distinct sectarian practices.

Towards inclusive heritage

Keeping this reading of Centhini Kadipaten in mind, the “abandonment” narrative that has been embedded into heritage-making around Java’s Hindu and Buddhist temples becomes a more ambiguous colonial and postcolonial framework. From the early 19th century onwards, colonial administrators-cum-scholars co-opted

The destruction of centuries past should focus the region on preparing for Indonesia’s next mega-eruption.

Fragile paradise: Bali and volcanic threats to our region

Re-introducing local texts is one strand in the decolonisation of thinking about the narratives of ancient temples in Indonesia. This strand does not intend to excavate something pre-colonial, but instead aims to retrieve localised knowledge from the cracks and fissures born out of local-colonial tensions. In order to better grasp nuanced historical contexts, local texts and artistic manifestations must be read closely. By studying history in this way, with sensitivity to political, social, and cultural contexts at the time of production, we relocate and observe what is in those cracks and fissures. It is through localised knowledge, such as the stories attested in the Centhini Kadipaten, that we can see how Hindu and Buddhist temples in Java were never truly “dead”, and that local people continued, and still continue, to re-create meanings and values around them. This new understanding should engender a more inclusive heritage practice, by acknowledging the diverse ways of interpreting ancient sites.

• • • • • • • • • •

This post is part of a series of essays highlighting the work of emerging scholars of Southeast Asia published with the support of the Australian National University College of Asia and the Pacific.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss