The damage from Malaysia’s latest financial scandal runs deep. Here’s how it will impact politics in the long-term.

The beans have been counted, the (foreign) prosecutors have stripped off their gloves, and the convoluted flowcharts have been pasted across the blogosphere.

1 Malaysia Development Berhad, better known as 1MDB, has once again lifted Malaysia to the world’s front pages—as usual, for all the wrong reasons. The saga and spectacle are both terribly disappointing and terribly predictable, after decades of eroding checks and balances.

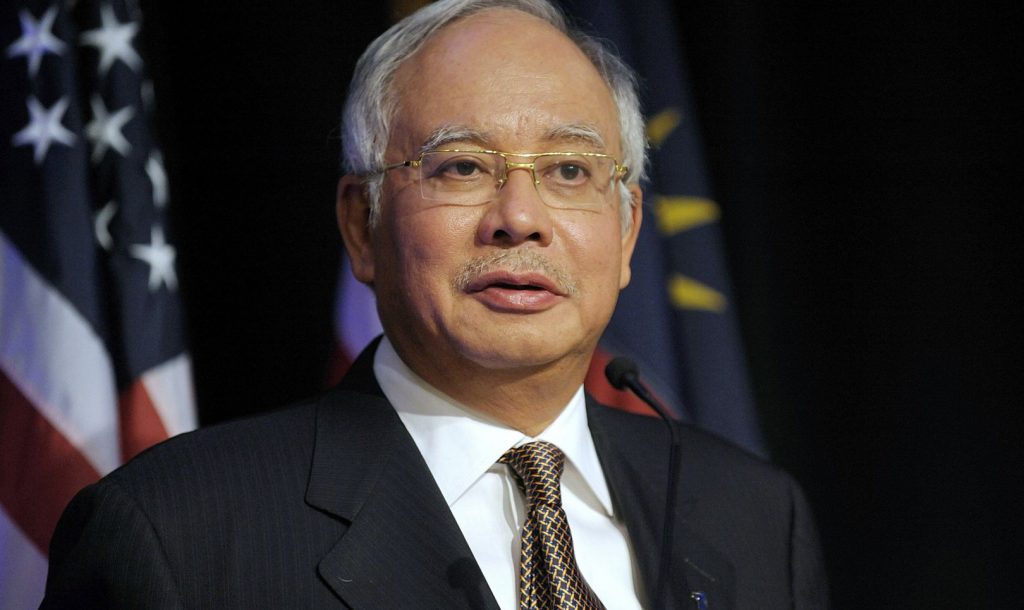

The sheer scale of malfeasance is daunting. The recent United States Department of Justice (DoJ) indictment was detailed and damning, the “Malaysian Official 1” euphemism notwithstanding. Yet 1MDB is the tip of the iceberg. Even if some losses are recouped and/or some political heads roll, the collateral damage runs far deeper and will be much harder to fix. Four aspects in particular bear attention, as we consider the longer-term political implications of 1MDB.

First, the unfolding facts reveal serious political-economic pathologies. While developmental statehood is not what it once was (or at least, aspired to be), a key legacy is the substantial role of the state in development, particularly via government-linked corporations, sovereign wealth funds like 1MDB, and similar vehicles. For such institutions to function effectively and in the public interest requires consistent, convincing probity. Beyond siphoning away funds, public sector mismanagement and opacity signal more systemic institutional weakness and corrode popular confidence in government decision-making locally, and in Malaysia as a reliable partner globally.

Second, Malaysia’s homegrown media have been sufficiently battered that it has been up to a London-based muckraking website, Sarawak Report, and the US-based Wall Street Journal to do the heavy lifting in investigative journalism. When Malaysian-based media stepped in—most notably, from the Edge Media Group—the state lashed out punitively, though without deterring independent media from continuing their coverage. We might consider this pattern as a novel form of ‘boomerang journalism’ (adapting Keck and Sikkink’s notion of boomerang activism), in which ‘contentious journalists’ outside Malaysia amplify the efforts of those inside (much as anti-corruption initiatives overseas compensate for the lassitude of domestic ones).

But that balance is unfortunate, and speaks poorly to the availability of information essential to any functioning democracy. Revivifying Malaysian mainstream media will require training new cohorts of personnel (in part, to replace those who have resigned in frustration with the constraints under which they work), regenerating a culture of journalistic integrity and vigilance, and cultivating confidence among editors and publishers. Online media play a role, but print, television, and radio are at least as important.

Third, that a financial scandal has been reframed as an ethnic contest—Malay–Muslims versus Chinese—is hardly intuitive, but likewise hardly surprising in Malaysia. Prime Minister Najib and his allies have fought accumulating allegations not by proving them wrong, but by an aggressive game of ‘wag the dog’: forget corruption; Malays have to stick together to secure hudud.

That tactic seems to be working. By all accounts, the Malay-Muslim ‘heartland’ in particular seems willing to give Najib a pass. Even if a substantial proportion rely largely on filtered mainstream news, chances are slim that many remain entirely unaware of the ongoing revelations. Rather, a combination of targeted patronage, Najib and his party’s position as communal saviour, and the abstract distance of a financial scandal render the proffered frame of Islam-under-attack effective. The resultant ethno-religious polarisation could take decades to redress, or could do permanent damage to the framework of Malaysian civic life.

The unfolding scandal has not gone unchallenged, nor are all the critics from the opposition side—although those within Najib’s United Malays National Party (UMNO), and not yet given the boot, must be particularly flummoxed.

Fourth and finally, the overall failure to translate aggravation into action indicates problematic ossification within UMNO, the opposition, and civil society alike. That ex-prime minister Mahathir Mohamad has been reconditioned in his 90s as a reformist hero is startling, and speaks poorly for the availability of younger, newer, less baggage-laden opposition alternatives. That the ‘progressive’-wing civil societal response to the DoJ’s kleptocracy charges is a fifth Bersih leaves one to wonder why this iteration of mass protests should be the charm. (Meanwhile, the right-wing plans yet another Malay-rights rally, reflecting and amplifying the communal bogey.)

Meanwhile, Najib’s government has struck back at detractors, further degrading already-battered freedoms of speech and association and complicating civil societal activism, including with a newly-enacted National Security Act. Should these laws eventually be loosened or lifted, as for the press, it will take the average citizen and voter some time to shake off the sense that speaking out is risky or inappropriate. The longer that process takes, the thinner and more tattered the fabric of social capital will become.

As a parliamentary democracy, at least in form, Malaysia should be able to put the matter to the test, through a vote of confidence in parliament. However, not only does UMNO set the parliamentary agenda, but UMNO’s many branches and their leaders face a collective action problem in coordinating against a party president, the prime minister, who controls campaign-funds and patronage purse-strings.

Meanwhile, the red cape of political Islamisation distracts the opposition as much as it does UMNO’s own mass base, leaving the opposition coalition in disarray when it most needs coordinated resolve and common purpose. The 1MDB debacle has revealed the paucity of political imagination and the frailty of participatory machinery and channels in today’s Malaysia.

At this point, enough countries are investigating 1MDB and its and Malaysia’s leaders that surely (surely?) something has to give. But the sad reality is, at this point, a court case, a criminal conviction, even a full overhaul of political leadership would not fix the problem. 1MDB has both laid bare and made worse deep weaknesses and ruptures in Malaysia’s politics, economy, and society.

As a quasi-neutral observer, my only hope is that we have hit rock-bottom—that the hat-tricks and hate-mongering will no longer work their magic; that the ranks of UMNO leaders will decide it’s worth the risk of a serious probe and full follow-up; that smart minds on both sides of the aisle will be able to revitalise political institutions; that civil society will find new ideas and fresh voices and stores of cleavage-bridging social capital.

At this point, though, optimism is about as hard to find as answers.

Meredith Weiss is Professor of Political Science at the Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy, University at Albany, State University of New York.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss