In a NM series he called ‘Starting Points’ Nicholas Farrelly attempted to prompt discussion about countries in Southeast Asia Asia by focusing on individual books, and he chose my Politics of Ritual and Remembrance: Laos Since 1975 (1988) for his ‘Starting points: Laos in 1975’. He kindly remarked that it “is still one of the crucial texts.” But he had “no doubt that even since Evans’ work in the 1990s the conceptualisation of the revolution and its pivotal year has changed significantly. There is still much to say about 1975 and all that.” Indeed, there is.

Oliver Tappe recently asked me if I had considered producing a revised edition of PR&R and I replied that he was doing a pretty good job himself in his various articles. And, I had no wish to. But if I did produce a new edition of this book about social and political memory it would now have a chapter called ‘Forgetting Socialism.’ As I remarked in the original book, by the mid-1990s almost half the Lao population had been born since the fall of the Royal Lao Government and they had no concrete memory of it. Today more-or-less half the population has grown up since the collapse of Stalinist communism around 1990, and they have no memory of restrictions on personal movement and calls to build socialism. There is no examination of this period inside the country and it has become a kind of blank space.

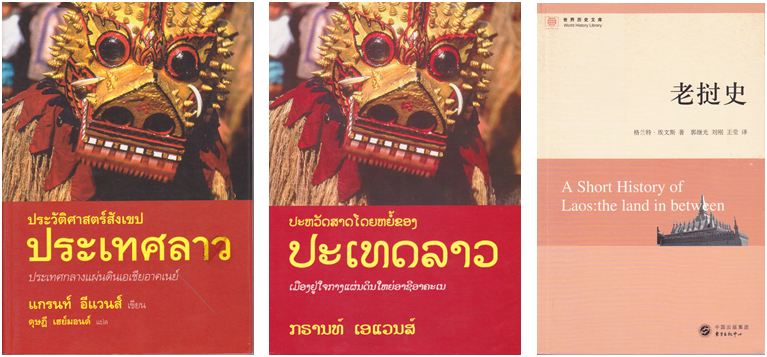

I have, however, revised my Short History of Laos: The Land Inbetween (2002) twice. First, for the editions that were translated into both Lao and Thai and published in 2006. Here the main revision involved splitting the chapter on the Lao PDR into two, with a new chapter called ‘post-socialism.’ The Lao translation did not endear me to at least some people in the foreign ministry and they refused my request for a research visa. Since 2009, however, I have had an expert’s visa through the Lao Institute for Social Sciences. (Short memories again?)

In 2011 a more thoroughly revised edition was published in Chinese by a Shanghai publisher, Orient Publishing Center, called simply Lao History.

In July 2012 the same text, plus or minus, appeared in English, published by Silkworm Books as a ‘Revised edition’. In it I have I tried to incorporate the insights I gleaned from Richard McGregor’s, The Party: The Secret World of Chinese Communism (2010) where he documents the pervasive control and influence of the communist party in China, despite liberalization. Much the same is true in Laos, and it would be nice to think that someone was working on a similar book about the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party.

Indeed, the recent reforms in Myanmar underline the differences between authoritarian and militaristic regimes and Marxist-Leninist ones. Aung Sang Suu Kyi would never have survived in Laos, Vietnam or China. It is something worth examining in depth.

Nicholas Farrelly invites further thoughts on post-1975 Laos, and in my revised edition I do just that in my final paragraph:

When the first edition of this book was written 10 years ago the collapse of global communism in the early 1990s was still fresh in my mind and it was not clear how the remaining socialist states, including Laos, would fare. In 2011 it is clear that they have fared very well, and they are likely to be with us for the next two or three decades. But one must quickly add, they are no longer recognizably socialist, while the one party state has become an instrument for the development of capitalism. People like me who were intellectually formed during the hey-day of the Cold War and at the end of almost a century of competition between revolutionary socialism and liberal democracies were unprepared for the transformation of Marxist-Leninist states into something more mainstream; merely another variant of the many paths that countries globally have taken into the modern world – for better or worse. Countries like Laos still carry baggage from the attempt to build socialism, but bit by bit it is being thrown overboard. The majority of the world’s and Laos’s population born since 1990 do not feel part of some global ideological struggle, but are simply swept along by an imperfect everyday reality. The hegemonic global mantra is ‘development,’ an often vague term promising a better future, and almost anything can be justified just by invoking it. It is a kind of modern magic, and it trumps any other card in the deck, including preservation of ‘a beautiful, ancient Lao culture,’ in the precious phrasing of the Lao Ministry of Information and Culture. Lao hope they can have their cake and eat it too; that they can have rapid all-round development that leaves their culture intact. This, however, is impossible. Lao culture and society is about to change much faster than anyone has anticipated, but just how much will remain of the culture that Lao now find so comforting and foreigners so charming, only time will tell.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss