Identifying historical traces of women’s same-sex sexuality and lesbianism is notoriously difficult in many societal and cultural contexts. Thailand is certainly no exception. Several scholars, both Thai and foreign, have written eloquent histories of Thai male homosexuality and homosocial spaces. Lesbians, however, rarely figure prominently in historical inquiries into Thai gender and sexuality.

Part of the reason for this imbalance, at least in scholarly literature, is the scarcity of empirical evidence. The few sources that do exist tend to be confined to elite groups of women and widely scattered across time. This does not mean, however, that the task of writing “Thai lesbian history” should be altogether abandoned.

The writing of history offers one way to tackle the social taboos that encapsulate lesbianism, and women’s sexuality more generally, in Thailand. Looking to histories of contemporary Thailand that pay attention to moments of same-sex intimacy, desire, or attachment between women can offer valuable insights into the operations of gender and sexuality at crucial moments in Thai history.

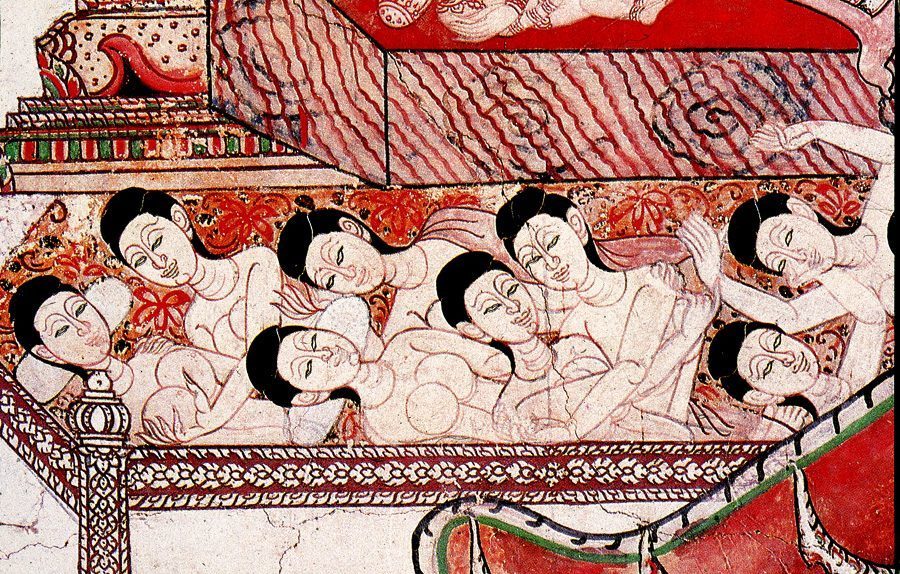

Sources concentrated at the elite level of Thai nobility indicate that the term len pheuan (เล่นเพื่อน) was used in the Ayutthaya and Bangkok periods to refer to same-sex practices among communities of palace concubines. Usually translated as “to play with friends”, the term len pheuan shows us that women’s same-sex intimacies were historically known, named, and strictly forbidden by various Thai monarchs, including King Borommatrailokkanat (r. 1448–1488) of Ayutthaya to King Mongkut (r. 1851–1868). These kinds of sources point to early forms of prescription around women’s sexual behaviour. It may also be possible to see the prohibition of len pheuan as an effort by the palace to monitor and maintain the all-important role of motherhood and royal pro-creation as a matter of state priority.

Another area worth examining is the historical trajectory of Kathoey (กะเทย), a category of identity that possesses a different set of social logics and expectations to the binary positions of “woman” and “man”—in short, Kathoey represents a third form of sexual/gendered subjecthood. Now exclusively used to refer to transgender women, or to men who identify or present as normatively feminine, the category Kathoey was historically available to either men or women who transgressed the appropriate norms of appearance and behaviour for their assigned sex. There is a wonderfully indignant quote from Anna Leonowens, the British governess who resided at the court of King Mongkut, that reads,

“Here there are women disguised as men, and men in the attire of women, hiding vice of every vileness and crime of every enormity.”

Sometime during the 1960s, the Kathoey category narrowed, and masculine-identifying women came to be associated with newer sex/gender categories, such as tom (from the English “tomboy”). More research is required to ascertain just what this period of redefinition and new category-making might mean for histories of Thai sexuality. Nevertheless, thinking about these changes is exciting, both for gender studies and Thai history more broadly, because such fluctuations in categories reveal sexual and gendered experience to be historically mutable and contested, rather than fixed.

The word “lesbian” itself has an interesting history of circulation and adoption. The transliteration of the English term “lesbian” into Thai as “เลสเบี้ยน” first cropped up in the late 1960s via pornography catering to heterosexual men. The impolite association of “lesbian” with commercial sex meant it was not immediately welcomed, with many women instead conceptualising their sexualities through gendered pairings of the more masculine-type tom and normatively feminine dee (from “lady”). Peter A. Jackson, the pioneering historian of queer Thailand, traces the first public utterance of self-defined “lesbian” subjecthood to the late-1970s and the Uncle Go Paknam columns in the magazine, Plaek (แปลก), meaning strange, bizarre, or “queer” in its older usage.

What is remembered, what is forgotten: A woman in a man’s shadow

A heroine of the Indonesian independence movement emerges from behind her husband's shadow

In conversations with self-identifying lesbian and queer feminist activists in Northern Thailand, the idea that lesbianism could stake claim to a “past” or “history” of its own was unfamiliar and, frankly, ridiculous. The notion of living openly as a same-sex orientated woman did not become a social possibility until the late 1970s (at the earliest), and it remains a subjecthood that carries significant restrictions depending on one’s class and social privileges. The documentary film Visible Silence (2015) by Ruth Gumnit shows us that “living openly” is still not an option for all, as queer women can encounter an array of social and professional consequences if their sexuality is known.

As the title of Gumnit’s documentary suggests, there is an eerie silence encasing lesbianism in Thailand. This is despite the many public gestures that are often framed as demonstrating state tolerance and social acceptance of gender difference and queer identities, including the ongoing discussions around same-sex civil unions and the recent announcement that Asia’s largest art exhibition on LGBTQ+ issues will be held at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC) late this year, to name just two examples. Writing new histories with greater attention to lesbianism, and women’s identities and roles more broadly, may help to break that silence.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss