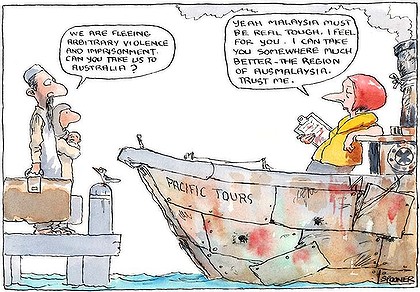

In May 2011, Prime Ministers Datuk Seri Najib Razak and Julia Gillard announced an agreement that up to 800 undocumented boat arrivals would be sent to Malaysiafor the UNHCR office to process their claims. In return Australia would resettle 4,000 registered refugees from Malaysia. Both governments, as members of the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime, saw the agreement as a win-win situation. Each claimed the arrangement would help ‘smash the people smugglers’ business model.’ In Australia, the reactions were loud and passionate, with the media making the most of each story.

But how did people in Malaysia react? The government? The opposition? Members of civil society?

Not everyone in Malaysia felt as positively as the Prime Minister about the arrangement. Opposition Leader Anwar Ibrahim called the deal a dubious one ‘whose legality must be investigated.’ In a later interview he said he did not think the Australian Government could expect Malaysia to support a program that runs contrary to the whole principle of the rule of law and constitutional rights to the sea.

When the High Court of Australia ruled the deal between the two countries to be unlawful, Home Minister Hishammuddin said that while Malaysia and Australia would respect the court’s decision they would find new ways of combating human trafficking. This means the arrangement could still be repackaged and presented as the only viable solution for dealing with Australia’s uninvited boat people.

The English language daily New Straits Times published an editorial which expressed disappointment that the Australian court decided the agreement between Malaysia and Australia ‘was not good enough,’ pointing out that it ‘is a binding contract … and has the force of the law.’

When international organisations such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Amnesty International drew the world’s attention to Malaysia’s treatment of asylum seekers, the Malaysian Government was, no doubt, embarrassed to have its human rights record exposed in such a way. In its 2010 Report Human Rights Watch (HRW) described the government sanctioned paramilitary group Ikatan Relawan Rakyat (RELA) authorised to check travel documents an ‘ill-trained, abusive civilian force’ which was arresting refugees in their homes without the necessary warrant. The independent Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) was critical of Malaysian authorities for breaking their pledge to improve conditions for undocumented arrivals.

Within Malaysia, Tenaganita (which promotes the rights of women, migrants and refugees) was among the non-governmental organisations (NGOs) protesting during the signing of the agreement. Lawyers for Liberty called the Malaysia Solution ‘scandalous.’ In March 2011 the President of the Bar Council, said that Malaysia was not up to the mark for an asylum seeker swap.

In ‘Our migrant hell-holes‘ Angeline Loh documented the deaths of detainees due to delayed access to medical treatment. She also reported that camp officials were known to confiscate medication from (e.g. diabetic) ‘inmates.’ Maternity support was said to be non-existent, food inedible, and visitors prevented from bringing medicines or soap to the detainees.

Established by the government in 2000, the Malaysian Human Rights Commission (SUHAKAM) sought to liaise with government departments, the UNHCR, NGOs and individuals to address the plight of detained children, but its impact on government policy remains limited. The human rights NGO Suaram (Suara Rakyat Malaysia/Malaysian Peoples Voices) also highlighted the plight of refugee and asylum seeker children, even though Malaysia had ratified the Convention of the Rights of the Child.

Health Equity Initiatives (HEI), committed to advancing the right to health, particularly mental health, of marginalised populations through its programs, also expressed concern over the treatment of refugees in Malaysia.

So far as the Malaysia Solution is concerned mainstream newspapers in Malaysia tended to report factual information including developments inside Australia. It was left to the social media and smaller media outlets to expose the plight of asylum seekers. Meanwhile in both countries justice for refugees and asylum seekers remains as elusive as ever.

Rita Camilleri is Adjunct Research Fellow Monash Asia Institute

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss