In May 2025 Malaysia’s Ministry of Home Affairs announced that migrant workers would be permitted to change employers across different industries. This could mean a potential break from the country’s employer-tied visa system. Yet the 13th Malaysia Plan launched two months later instead explicitly flagged tightening migrant workers’ permit conditions in ways that would limit their eligibility to change industries and employers, placing restrictions on their doing business and shortening work permit durations.

This policy change and contradiction occurred under the leadership of the Pakatan Harapan government that has repeatedly presented their administration as reformist, emphasising transparency, accountability, and concern for migrant rights. While such plans have been announced, these competing policy proposals operate within an unchanged regulatory or legislative framework.

As detailed guidelines have yet to be launched, the key question is whether to expect a meaningful shift in addressing power imbalances and debt dependency in the migration system. Will it translate into equitable labour conditions for its migrant workers, particularly as Malaysia’s rapidly ageing workforce is set to deepen reliance on foreign labour? With this current contradictory policy backdrop, it is critical to examine how employment structures shape migrant workers’ everyday realities, specifically through social exclusion and institutionalised debt.

Malaysia’s migration governance

Migrant labour has long been essential to Malaysia’s economic development, as the country has relied on migrant workers for decades to fill workforce shortages in key economic sectors. Such shortages were recently exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic which led to a government-imposed freeze on foreign worker recruitment and caused a significant dip in the number and share of migrant workers in the labour force. As a result, Malaysia continues to experience acute labour shortages, especially in labour-intensive industries such as manufacturing, plantation and construction. According to employment associations, the labour shortfall is estimated at 1.2 million, while the Ministry of Economy places the gap at 400,000 workers as of the end of 2024.

The import of low-wage foreign workers has been politically convenient: it placates owners of labour-intensive industries, sustains price competitiveness in export-oriented sectors, and provides political elites with rent seeking opportunities through the outsourcing of migrant recruitment and licensing to the private sector. The result is a migration system that institutionalises temporary, disposable labour characterised by high recruitment costs on workers—who remain cheap to hire, easy to control, are barred from social integration and are denied transparency in recruitment processes.

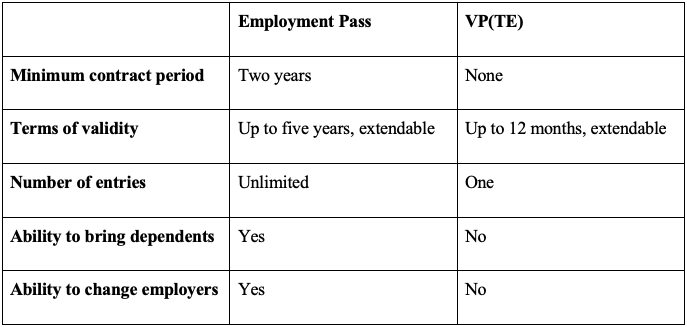

But the Malaysian government has been reluctant to reform its recruitment and visa system, even though such reforms could ease labour shortages and protect both employers’ and workers’ interests. The system is built on a worker-funded model where the financial burden of securing employment is placed largely on the migrant workers themselves. While the degree of cost-sharing varies by nationality, sector, region and company, this model disproportionately impacts low-wage workers. Malaysia has a two-tiered work permit system for migrant workers to distinguish those employed in low-skilled jobs (“foreign workers”) and high skilled jobs (“expatriates”). Low-skilled migrant workers are granted a Visitor’s Pass (Temporary Employment) (VP(TE)) / Pas Lawatan (Kerja Sementara) (PL(KS)), while mid- and high-skilled migrant workers are granted an Employment Pass (EP). The VP(TE) permits migrant workers to work in Malaysia for a maximum of 10 years, which needs to be renewed annually, incurring recurring costs.

Source: Bar Council Malaysia (2019) “Migrant Workers’ Access to Justice: Malaysia”; Immigration Regulations 1963

The migration process is guided by a “stop-go” system, with shifting quotas and frequent freezes on admissions. According to the Independent Committee on the Management of Foreign Workers, the continued demand for foreign labour highlights the domestic labour market’s inability to keep pace with industry demands—particularly in terms of the numbers of workers required. In the absence of a long-term labour force strategy, migration policies are often made reactively and under pressure, resulting in inconsistencies.

Reform attempts since the election of the Pakatan Harapan government in 2018 include the establishment of the Independent Committee on the Management of Foreign Workers by the Ministry of Human Resources (MOHR). Besides that, the Private Employment Agencies Act was amended in 2017 to regulate private employment agencies and terminate outsourcing of foreign worker recruitment services. In tandem to this, there was the introduction of a zero-cost recruitment model with Nepali workers in 2018, shifting to an employer paid model where migration costs would be covered by employers to prevent workers being debt bonded. There were also plans to extend this model to other countries such as Bangladesh. However, these reforms have not fully translated into better recruitment practices and working conditions for migrant workers.

Efforts to reform this migration governance run into the same political barriers.

First, employers in low-wage sectors oppose any cost shift from workers to firms, arguing it would undermine competitiveness and spur relocations abroad. Earlier iterations of moving towards an employer-paid model include the Employer Mandatory Commitment (EMC) policy, which holds employers of foreign workers responsible for paying applicable foreign worker levies. But by 2013, the system reverted to requiring migrant workers to pay levies due to pressure from employers.

Second, state rent-seeking practices. The migration brokerage chain is a lucrative revenue stream for politically connected actors. As key public sector responsibilities are outsourced to preferential private companies that play a major role in both recruitment and in-country administration of foreign workers, this creates an environment conducive to rent-seeking practices throughout the recruitment chain. Inflated fees, hidden charges and collusive practices raise the overall cost of migration, which is often passed on to both employers and migrant workers.

Indonesia’s killer commodity

The kretek cigarette industry and its devastating public health impacts are sustained via a huge apparatus of labour, and appeals to cultural nationalism

Layered onto these structural factors is the political narrative surrounding Malaysia’s migrant workers. Public attitudes towards migrant workers have become even more negative over the past decade, often attributing the higher volume of migrant workers to social threats linking them to crime rates and believing they have a negative effect on the economy. Political parties have amplified these sentiments, at times instrumentalising migrant communities for electoral purposes or religious identity campaigns.

Against this backdrop, there are two structural conditions of VP(TE) employment that shapes the lived experiences of migrant workers in Malaysia: social exclusion and institutionalised debt. VP(TE) holders are explicitly prohibited from marriage or cohabiting with their spouses or families in the country, reinforcing a narrow, extractive model of temporary migration. At the same time, debt is not incidental but integral to the migration process that facilitates control and exploitation. Meaningful reform should account for a migration policy that reflects actual labour conditions and social realities of its labour force.

Uprooting the social foundations of plantation life through VP(TE)

The current visa system poses challenges across many sectors, but its consequences are especially profound in the palm oil industry. In palm oil plantations—particularly in Sabah, Malaysia’s largest palm oil producing state—the scheme fails to adequately address migration and labour issues. Its implementation reveals weaknesses, particularly in the lack of clear information provided by employers, both regarding the policy’s requirements and the costs involved. Workers we interviewed often say they are unaware of what is covered by the VP(TE). All they understand is that they must renew their work permits annually, with monthly wage deductions ranging from RM100 to RM150 (US$23 to US$35), which often continue for over a year.

But most importantly there is a context that is often overlooked: palm oil plantations are highly remote and isolated. It is difficult to imagine workers sustaining themselves in such an environment without performing essential functions of social reproduction (i.e. work that is necessary to reproduce their labour power). This contrasts, for instance, with the urban service sectors, where workers can live with fellow workers and have access to recreational spaces. This isolation prompts workers to bring their families with them. Typically, men migrate first and, after securing employment on the plantation, send for their families or marry other migrants who are already working there.

Previous studies have shown that plantation life, whether on palm oil, tea, or coffee estates, is often organised around family units rather than individual workers, a pattern common across plantation economies in Southeast Asia. On many palm oil plantations, both spouses work; in some cases, wives take on domestic responsibilities, while children help out during their free time. Yet the VP(TE) scheme prohibits migrant workers from marrying or living with their families, even as it depends on the logic of family labour. This structural contradiction effectively criminalises the survival strategies that keep plantations running.

The World Bank estimates that between 2018 and 2020, Malaysia hosted up to 5.5 million migrants, with half of them undocumented. Official data states that around 337,000 migrant workers are employed in Malaysia’s palm oil sector, but some estimates suggest the actual number exceeds one million and the majority are undocumented. In other words, one of Malaysia’s key economic sectors depends heavily on undocumented labour. In porous border states like Sabah and Sarawak, undocumented migration occurs daily. Yet rather than managing this flow in ways that protect workers, immigration policies (including the VP[TE] scheme), reinforced by the logic of deportability, have contributed to the illegalisation of migrant workers, leaving them with little choice but to end up in undocumented enclaves such as palm oil plantations and semi-urban areas, where they become cheap labour and easily exploited.

VP(TE) and reproducing debt dependency

The VP(TE) is key in shaping Malaysia’s migration system, structurally embedding debt dependency among migrant workers, which reinforces forced labour vulnerabilities. The pass is tied to one employer and must be renewed on an annual basis, imposing recurring administrative costs estimated at RM7,500 (US$1,826) per year—often externalised to the worker. These costs compound on already substantial pre-employment recruitment fees, creating a cycle of debt and dependency that traps workers in their jobs.

Pre-employment costs routinely exceed legal limits. IOM reported that pre-employment costs for Indonesian migrants’ legal ceiling was supposed to be under RM1,631 (US$357), yet reported averages reach RM1,828 (US$401). Meanwhile, Bangladeshi workers, whose ceiling was RM8,599 (US$1,885), reportedly pay up to RM14,089 (US$3,090) on average. These inflated costs paid by migrant workers can sometimes be up to 6 times the legal ceiling, taking more than a year for workers to repay. The result is a workforce wedged in perpetual debt, with limited alternatives before they arrive in Malaysia. Between 2018 and 2023, a study surveying 500 Bangladeshi workers in Malaysia found that 96% of them had fallen into debt due to recruitment fees.

Crucially, this recurring cost structure is not incidental but systemic, reinforced by the outsourcing of key public sector responsibilities—once handled by the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Ministry of Human Resources (MOHR), and other agencies—to preferred private companies. These private actors play a major role in both recruitment and the in-country management of migrant labour, resulting in an increasingly fragmented, inefficient and opaque system conducive to rent-seeking practices. Inflated fees, hidden charges and collusive practices raise the overall cost of migration, which is often passed on to both employers and migrant workers.

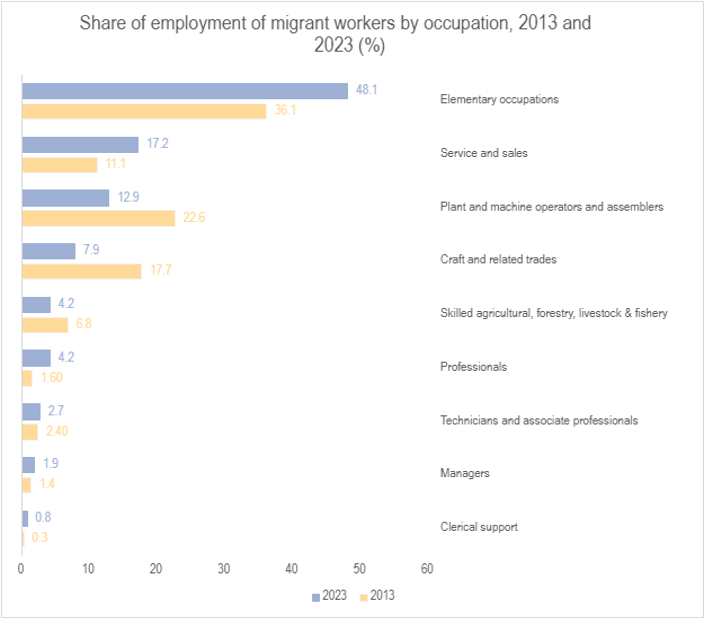

This debt-based model is compounded by Malaysia’s employer-tied visa restrictions that trap workers in their jobs. VP(TE) prevents movement between employers or better jobs even within their own sector, unable to seek better opportunities or when working conditions deteriorate. Malaysia Standard Classification of Occupations (MASCO) classifies employment structure as 10 major groups with Group 9 as “elementary occupations” defined as “requiring skills at the first level” with sub-major groups under this category including cleaners and helpers; agricultural, forestry, farming and fishery labourers; and mining, construction, manufacturing and transport labourers. Figure 1 shows that 48% of migrant workers are employed in “elementary occupations” in 2023, with the remainder concentrated in service and sales (17%), and plant and machine operation (13%). With the steep increase of elementary occupations (33% over the last decade), this reflects restricted mobility and labour market rigidity. This occupational clustering is not coincidental but rather a product of enforced labour market rigidity. Most workers in these roles earn below the minimum wage of RM1,700 (US$399), further reducing their ability to quickly recover their debt. In this context, debt bondage is structurally produced as the norm, not the exception.

Figure 1: Elementary occupations make up almost half of Malaysia’s foreign workers, increasing over the last decade. Source: Department of Statistics Malaysia, Labour Force Survey 2013 and 2023

Debt repayment is not merely a background concern but also a central obstacle to effective implementation of labour mobility reforms. With MOHA and MOHR’s announcement on granting employer and sector mobility to those who hold VP(TE), the policy shift should also look to redesign rent-seeking incentives within the current migrant labour brokerage to ensure the shift is substantive. Comparative evidence from the region reveals the potential and limitations of employee mobility reforms. In the case of South Korea and Thailand, the criteria to change employers for migrant workers is legally allowed but is often too challenging to meet, especially when a migrant worker has debt repayment obligations or seeks to leave an exploitative workplace for better working conditions.

Designing employer and sectoral flexibility can significantly dismantle the debt bondage pathway if the legal possibility of mobility translates into migrant workers’ actionable agency. Protection mechanisms should be in place to ensure migrant workers would be able to leave abusive employers without fear of retaliation or deportation. A transfer policy that allows workers to seek new employment without their current employer’s consent—and without re-triggering the cost cycle—would mark a meaningful move. This policy was once adopted by Singapore, which allowed workers to change employers without seeking approval from their present employer and would be enrolled in retention schemes where industry associations facilitate job-matching, which is now adjusted.

Malaysia’s labour migration model reflects broader trends in South–South temporary migration systems, where predominantly male workers are managed through brokerage chains. These processes are shaped not only by regulatory intent but by commercial incentives, prioritising short-term labour supply over sustainable labour management.

Moving forward

What is needed is a migration policy that accommodates the specific characteristics of the labour force in the palm oil industry and other key sectors, while taking into account the different geographies of labour migration across Sabah, Sarawak, and Peninsular Malaysia. The current model prohibits family-based labour

Indonesia’s killer commodity

The kretek cigarette industry and its devastating public health impacts are sustained via a huge apparatus of labour, and appeals to cultural nationalism

In the context of Sabah, some activists have even proposed developing border infrastructure to support cross-border commuter migration as a realistic solution. Many migrant workers do not intend to settle permanently in Malaysia: they long for their home villages, work to save money, and envision a future back in their places of origin. Some have even managed to return home after working for decades. If such aspirations were supported by policies that enable legal, temporary mobility, there would be little reason to view migrant workers as a threat or a burden.

Meanwhile, undoing the employer-tied visa provides an opportunity to address the triad of rent-seeking, debt burden and social exclusion, or otherwise risk reshuffling the country’s migration system rather than transforming it. Withosut such steps, the VP(TE) will remain a vehicle for redistributing the production of debt and dependence, rather than ending it.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss