There is an anecdote told among close acquaintances of the late Tun Dr Ismail Abdul Rahman, Malaysia’s feared and respected Deputy Prime Minister and Home Affairs Minister in the early 1970s, that he once in confidence said that he felt he was at heart a greater racist than in his actions, unlike most of his politician colleagues, who were more opportunistic and were racists in words and deeds, but not at heart.

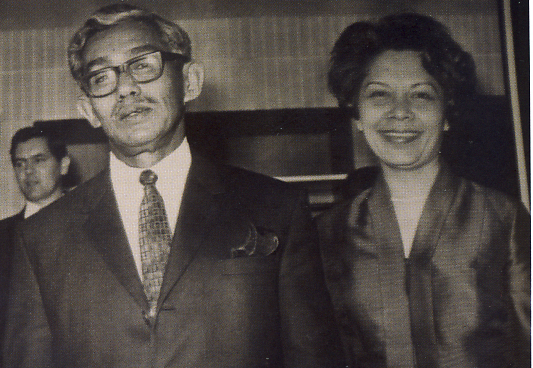

And yet, he was the Malay leader that Chinese Malaysian leaders of his day trusted. In fact, even Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore has often reiterated that Tun Dr Ismail was the only Malaysian leader he had faith in.

As a reflection of the Malaysian culture prevalent during his time perhaps, many of his best friends throughout his life were non-Malays. When Tun Dr Ismail was growing up in Johor Bahru, among his family’s closest friends were the Cheahs, the Kuoks and the Puthuchearys.

Dr Cheah Tiang Eam was a medical doctor who was very close to Ismail’s father, Abdul Rahman Yassin. Ismail’s elder brother, Suleiman, later a member of Malaya’s first Cabinet, was sent to the Cheah home to learn English manners from Mrs Cheah, who was an English lady. Ismail was especially fond of the youngest Cheah daughters, who later married the Kuok brothers, Philip and Robert. The Kuoks would be among Ismail’s closest friends in adult life.

The painful process of securing independence and negotiating a workable path of nation building in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s seared the ever-present issue of race onto the political foreground, where it has stayed until today. Racial issues submerged consciousness of the inter-ethnic exchanges and cultural hybridisation, which continued nevertheless. Understandably, in many Malaysians, strong ethnocentric emotions were stimulated for a time, something that the ensuing politicking would not allow to dissipate.

What went wrong, of course, when we look back over the last few decades, was that they allowed themselves to be manipulated into seeing themselves exhaustively in racial terms and not in citizenship terms. The political establishment grew to depend on this discourse, and turned it into a chronic pathological state.

The golf handicap

Where policy making was concerned, Tun Dr Ismail saw racialism as a technical issue, and not a matter of rights. An unhappy and unacceptable historically given socio-economic condition had to be rectified for the country to move on–and that condition happened to have an extremely strong ethnic element to it. That was the reason why Malaysian politics had to have such a strong racial slant. It was a historical contingence.

One of his more memorable ideas was his famous use of the golf handicap metaphor to explain affirmative action for the Malays –the NEP.Having the handicap system is meant, firstly, to allow those weaker in the sport to participate, and secondly to provide these newcomers with opportunities to improve their game and to lessen their handicap successively. The aim is for as many players as possible to have as low a handicap as possible.

Realising the danger that the NEP could devolve into an exercise in Malay entitlement if not properly handled, he pushed for a twenty-year limit to be put on it.

The poignant point in Tun Dr Ismail’s admission about his feelings–and it is one that forces all of us to be sincere at least to ourselves–is that what makes a man good and a leader great is not what his innermost feelings are but how he rises above them.

As the celebrated scholar Prof Wang Gungwu once told me: “We are all racially biased in our feelings at some level; but what is essential is how we rise above them in our actions”.

This attempt at rising above his feelings was what enabled Tun Dr Ismail to reach across ethnic divides. It was also well-known that he strongly disliked the term “Bumiputera” and feared that it would disunite Malaysians. He felt it best not to confuse the issue by lumping Malays with other groups.

Tun Dr Ismail enjoyed widespread respect from all who knew him and instilled awe in his subordinates because he could not stand fools. That trait is more important than one might think. If one takes the duties of leadership as seriously as he did, then subordinates or peers who did not feel a sense of urgency in what they did actually undermined his labours.

In fact, he was feared as a medical doctor as well, never tolerating patients who showed signs of self-pity and who were psychosomatic. As his Johor Bahru neighbour Robert Kuok would later say, “Doc would not have fared well running a medical clinic”.

Politics became Ismail’s calling instead, and self-discipline, practical wisdom, and a strong ethical sense would mark his career. He could not stand corruption either, as was seen in how he with a shouted threat of prosecution sent away a Chinese vendor who had delivered vegetables and other goods to his home as gifts for his family.

Despite being Home Affairs Minister, it was nevertheless Tun Dr Ismail’s vision of a neutral Southeast Asia which came to define the country’s foreign policy that has remained so successful and consistent till this day.

As Tun Abdul Razak’s main confidante, he exerted a greater influence over the early years of Razak’s premiership than is normally assumed. When news of his demise in September 1973 reached Razak in Ottawa where the prime minister was attending a Commonwealth meeting, the latter practically collapsed and had to be medicated. Tun Razak later lamented: “Whom shall I trust now?”

Tun Dr Ismail has been dead for 40 years now, and Malaysia has changed greatly. But his legacy of inclusion and moderation, and honest and honourable leadership, is unforgettable and can yet inspire new generations of Malaysians from both sides of the political divide to lead with wisdom.

Perhaps we will yet see a Malaysia that strives to unite its people; that spontaneously celebrates its diversity; and that acts on universal human principles instead of demeaning opportunism.

I would venture that that was the Malaysian Dream from the very start.

Ooi Kee Beng is the author of the award-winning bestseller The Reluctant Politician: Tun Dr Ismail and His Time (ISEAS 2007). He is the Deputy Director of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss