Toshihiro Yoshida’s journey into northern Burma in 1985-1988

There have been numerous Japanese tales in Burma’s periphery. Some Japanese even participated in cross-border combat activities with ethnic minority armed groups, and a few of them published written accounts. Takazumi Nishiyama, the author of the book mentioned by Andrew earlier in these pages, was one of them. I have not read his book (as it is not easy to get hold of a copy). But Nishiyama’s writing left on the internet is remarkably thoughtful, showing that he made the decision to join the Karen army as once-in-a-lifetime commitment. The book is well-known among the Japanese who are interested in the contemporary Karen situation on the border, but outside this rather small circle it is not a widely recognizable title. It was never re-printed and is out of print today.

The best-known Japanese cross-border adventure into Burma in English is Hideyuki Takano’s outrageous misadventure to the Wa land. The Shore Beyond Good and Evil: A Report from Inside Burma’s Opium Kingdom presents a story of a young Japanese man’s seven-month life in a Wa village (from October 1997 to May 1998). There he grew – and in the end was hopelessly addicted to – opium. Despite the grandiose English title, Takano is a humor writer and this book is self-consciously hilarious. Unlike Nishiyama, Takano was driven not by political commitment but by shameless curiosity. While he routinely gets drunk with fellow Wa villagers until he passes out, Takano turns out to be an honest and acute observer, and his book gives such a rare glimpse into day-to-day life in a Wa village. (It is said that Khin Nyunt found out about this book from the Japanese ambassador and he had it translated into Burmese. In recent years Takano has been visiting Burma legally. It is remarkable that the Burmese government grants him a visa!)

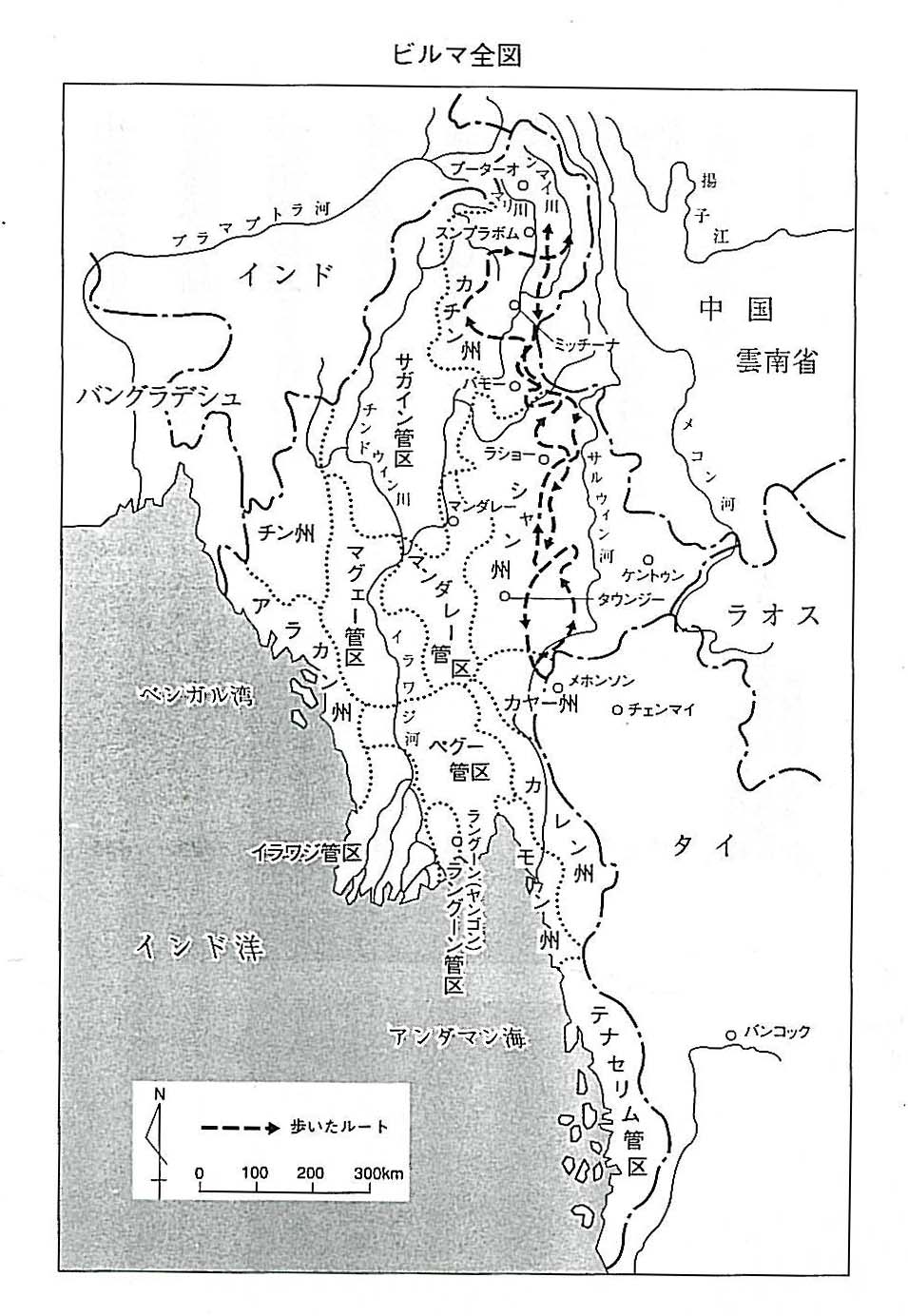

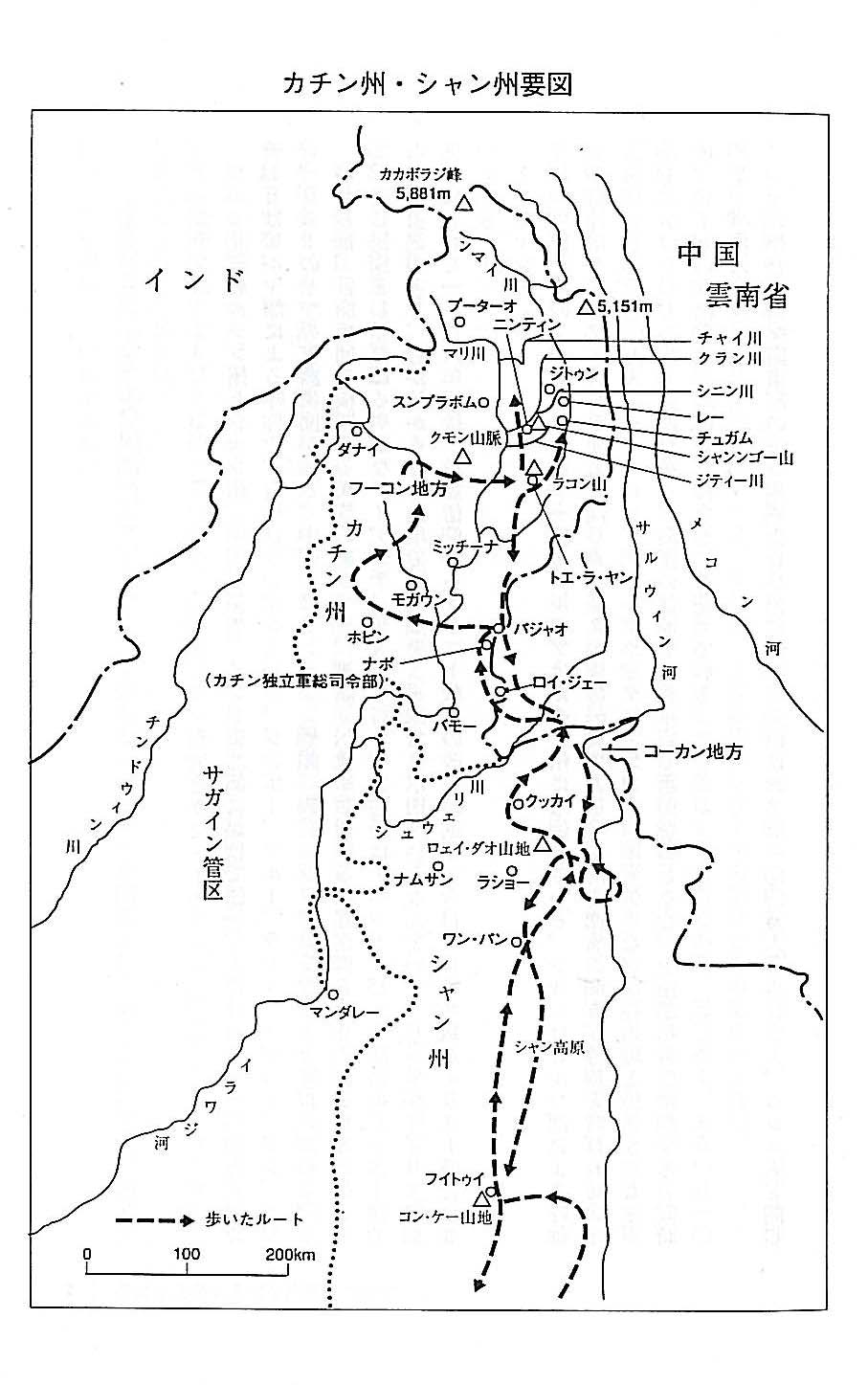

Of all the Japanese cross-border journeys into Burma’s periphery, however, those by Toshihiro Yoshida are regarded as the most valuable. Yoshida started visiting Shan villages in 1977 when he was a college student. In January 1985 Yoshida crossed the border from Mae Hongson to Burma, and in March he left the KNPP headquarter with KIA troops going back to Kachin State along the Salween River and then through the Shan Plateau. Until October 1988 – that is, for three years and seven months – Yoshida crisscrossed northern Burma, primarily Kachin State, with KIA soldiers. (Incidentally this is also the time that Bertil Linter was traveling in the same part of the country-a journey resulting in his Land of Jade.) Here are two maps of his journeys:

Nishiyama died from malaria he got in Karen. Takano developed a hideous skin disease in Wa. In Kachin, Yoshida too suffered seriously from malaria and it appeared that his life was ending there, until a shaman miraculously saved his life. He returned to Japan with 31 notebooks and 2800 photos. It took another seven years until he managed to publish his first book. (It won the major non-fiction award in Japan in 1995.)

Yoshida learned to speak Jingpo fluently and in the books he offers exceptionally detailed descriptions of what he saw and heard in parts of Shan and Kachin States. He wrote in detail about remote villages and villagers-their houses, clothes, farming methods and tools, food, animals, plants, music, myths and legends, festivals and rituals, language, kinship structure and naming rules, etc. Yoshida writes about atrocious acts by the Burmese army. He also squarely speaks about the Japanese cruelty during WWII. (One day he came across a village that had been recently bombed by the Burmese air force. Then a village elder told him that the village had been bombed by the Japanese forty years ago.)

Yoshida’s interest in the end, however, is not in military or political affairs. What enthralled him most in northern Burma were the deep, mesmerizing forests, in which he saw the villagers skillfully conducting swidden farming. Despite the many deaths he encountered, Yoshida found dignity and richness in the lives of trees and humans in northern Burma’s deep forests. And he succeeded in capturing these qualities in beautiful, evocative prose.

What distinguishes Yoshida’s writing is the humility and respect with which he writes about the living and dying of ordinary people in northern Burma. I hope it will be translated into English. I am sure that his writing will be translated into Burmese (and hopefully Jingpo) when people there can read freely about their own country.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss