Bali’s largest volcano, Mount Agung, is showing signs that it may well erupt. Seismologists have reported frequent and intense tremors within the volcano since mid-September. The emission of steam puffs from the crater and swelling of the volcano’s surface indicate rising magma. Despite a comprehensive level of scientific monitoring, no-one can predict if or when volcanic material will begin to emerge.

[February 2018 update: in late November 2017, Mount Agung entered an eruption sequence, and small non-explosive emissions of volcanic material have been occurring on and off since then]

View of the summit of Mount Agung from the Besakih temple complex. (Photo: CEphoto, Uwe Aranas)

This uncertainty makes life difficult for people who live in the danger zones around the summit, because they have been compelled to evacuate with little control over their movements and no knowledge about how long they will have to wait before it is safe to return home. The Balinese community has been active in supporting these evacuees, but the humanitarian burden is very heavy, with around 140,000 people displaced by mid-October. The prospect of months of waiting for an eruption has prompted many residents to return to danger zones during the day in order to continue making a living.

The Long-Term Behaviour of Mount Agung

In anticipation of the eruption, many people have looked to Mount Agung’s past activities to understand the events to come. Most people talk about the eruption of 1963–64, because it is still within living memory. This was Indonesia’s most explosive eruption in the 20th century, classified as a large VEI 4 eruption with 0.8 km3 of ejected material. It was tremendously harmful to Balinese people living in the eastern part of the island, with widespread destruction of homes, agricultural land and wilderness, reaching the coast at several places. Bali’s major temple complex Besakih narrowly escaped damage from lahar flows, which came in repeated waves throughout 1963 and into early 1964. Over 1100 people were killed.

Depiction of the 1963–64 eruption by leading Balinese artist Ida Bagus Nyoman Rai (c. 1915 – 2000). This painting is privately owned. Source: The Virtual Museum of Balinese Painting

Fragile paradise: Bali and volcanic threats to our region

The destruction of centuries past should focus the region on preparing for Indonesia’s next mega-eruption.

A recent study of tephra deposits produced by Mount Agung have found that this volcano was particularly violent between the 14th and 20th centuries, with an estimated four VEI 4 eruptions and one VEI 5 eruption in this 700-year period. In this context, the 1963–64 event appears not as a freak occurrence, but one of a series of major eruptions that Mount Agung has experienced for the better part of a millennium. According to volcanologist Karen Fontijn, “Agung has a repeated history of volcanic eruptions that are very similar in style to the 1963 eruption”.

The Eruption of 1710–11

In this article, I focus on one such eruption that took place between October 1710 and February 1711, as it was recorded in Balinese historical texts. I look at three commemorative documents that were probably written within a few months of the eruption. These sources are brief but detailed, and they are attached to Balinese manuscripts that were copied and collected in the 1920s and 1930s. In obtaining the texts, I have relied on the publications of scholars such as Hans Hägerdal and Sugi Lanus who brought these manuscript sources to light.

One of the texts gives a breakdown of the eruption sequence, which began on 21 October 1710 when the summit “began to burn”. This can be interpreted as the emergence of lava spilling out from the crater. The note goes on to say that “ash rain fell on 2 December”, followed by “a torrent of fire on 12 December” and “a downpour of little stones on 16 December”. Later in that month, there was “a flood of large stones and mud”, and the earth was so disturbed that “ravines became hills and hills became ravines”.

These descriptions are consistent with an explosive phase, where volcanic material is erupted in a large column and then falls back to earth as ash, lapilli and volcanic blocks. The texts describe the destruction of villages, forests, rice fields, fruit plantations, and irrigation systems in the vicinity of the volcano. It is mentioned that over 600 people were killed in the coastal village of Tianyar, directly north of Mount Agung’s summit.

| Date | Event |

| 21 October 1710 | Lava flow |

| 2 December 1710 | Ash fall |

| 12 December 1710 | Explosive phase |

| 16 December 1710 | Lapilli fall, lahar flow |

| 1 February 1711 | Pyroclastic and lahar flow |

Timeline of the 1710–11 eruption sequence, reconstructed on the basis of textual sources

The Danger of Pyroclastic and Lahar Flows

The notes indicates that the explosive phase of December 1710 was followed by even more destructive phenomena: pyroclastic flows down the volcano’s flanks and the lahar floods that resulted from the mixture of pyroclastic material and rainwater. Since the 1710–11 eruption occurred during the rainy season, lahar seems to have been produced almost immediately. Lahar flows after 16 December 1710 affected villages to the southeast and the southwest of the summit.

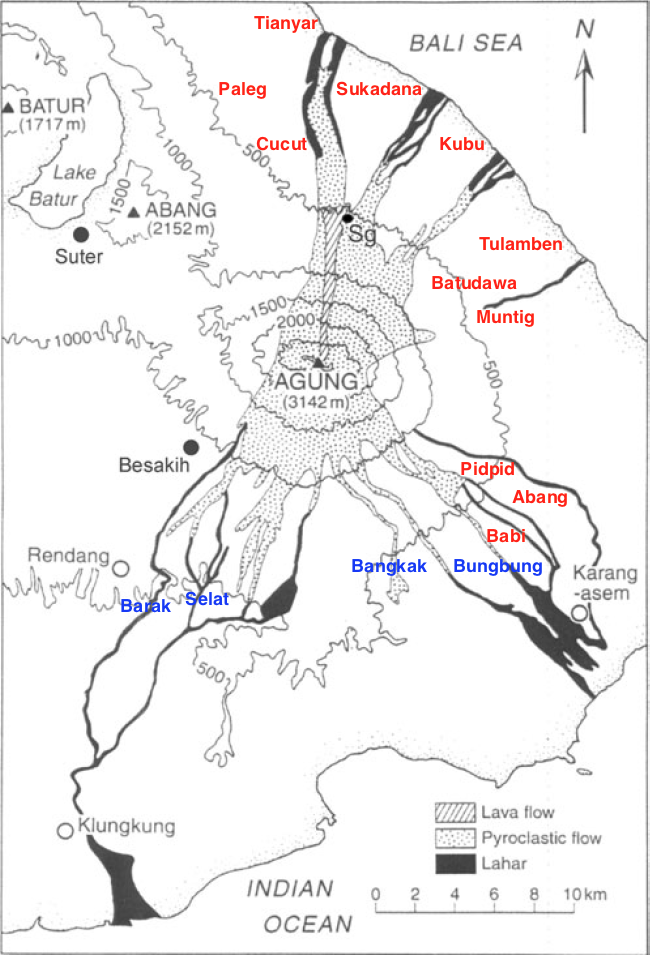

Further lahar flows occurred on 1 February 1711, seven weeks after the main explosive phase. These lahar flows are described in the notes as “a flood of hot water” that severely damaged settlements on the north coast in the present-day districts of Sukadana and Kubu. Mount Agung is surrounded on three sides by elevated land, which channel the pyroclastic and lahar flows into narrow river valleys radiating from the summit towards the north, the northeast, the southeast and the southwest. These are precisely the directions in which lahar flowed in 1963–64, and the same areas are currently designated as the most serious danger zones by the Volcanology Centre and the National Disaster Management Authority.

This map, adapted from a figure in Self & Rampino’s 2012 article, shows where the 1710–11 eruption caused damage to settlements (red) and river valleys (blue). The grey shaded areas indicate the directions of flows from the 1963–64 eruption.

The notes on the 1710–11 eruption describe how the pyroclastic material turned the rivers themselves into destructive lahar flows, destroying the paddy fields in the valleys of Bungbung and Yeh Lajang (southeast), Bangkak (south), and Selat and Barak (southwest). Irrigation was severely disrupted: springs were ruined, aqueducts were knocked down, and bathing places filled up with volcanic material. It is the pyroclastic and lahar flows that seem to have been the most damaging products of the 1710–11 eruption, just as was the case in the 1963–64 eruption.

The Use of Volcanic History

It is useful to study past eruptions of Mount Agung, even though it can be distressing. Descriptions of the human suffering caused by an 18th-century eruption may be traumatic for Balinese people who survived the 20th-century one, and they can frighten people whose lives and livelihoods are currently under threat. However, the evacuees and others affected by Mount Agung’s activity rely on access to accurate, timely and complete information about every aspect of the volcano. Its geological history can provide important context for people to understand how eruptions have affected Balinese communities in the past, and how best to minimise the damage in the event of another eruption.

If you would like to provide material assistance to the people affected by Mount Agung’s current activity, you can donate to an NGO called Kopernik, which is providing the most urgent amenities for evacuees. Up-to-date and accurate information in English about the volcano is available at Ubud Now & Then and Mount Agung Daily Report.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss