Myanmar is still in turmoil with more than eight hundred civilian deaths and five thousand imprisoned since the military (Tatmadaw) overthrew a democratically elected government on 1 February. After the evaporation of dialogue and political solutions, the role of groups with armed forces became more prominent. The post-coup stances of Myanmar’s nearly two dozen ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) that have fought against the military regime will be a determinant in the country’s future.

In my report for the SEARBO project, I outline the stances of eighteen ethnic armed organizations and their coalitions in Myanmar. In the first 100 days after the military coup began on 1 February, the EAOs diverse positions have been revealed through their public statements, activities and relationships with the military. Has the coup has brought these groups closer together against their common enemy? Or has the coup deepened their disunity, and the likelihood of the formation of the federal army?

Click on the cover image below to download the full policy brief.

Coalitions of the Ethnic Armed Organizations

Generally, the eighteen active EAOs in Myanmar can be divided into two categories: those that signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) in 2015 and those that did not. The NCA agreement was the first multilateral ceasefire agreement in Myanmar’s history. It is often described as hybrid agreement, as it also included political agreements such as a roadmap for political dialogue and a guarantee of amending, repealing, and adding to the constitution and other existing laws.

Signatories to the NCA formed the Peace Process Steering Team (PPST) in 2016 and it is now made up of ten EAOs. Four EAOs that had not signed the NCA formed a military coalition, the Northern Alliance, in 2016. A year later, these groups and another three non-NCA signatories formed the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC). These seven members of the FPNCC reportedly make up 70 percent of the troop strength of all EAOs in the country.

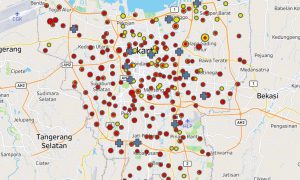

Mapping the stances of the Ethnic Armed Organizations

In order to identify the post-coup stances of the EAOs, this report reviews their individual and group. The EAOs’ statements, activities and engagement with the military can be analysed through a framework based on two dimensions: political and military. The political dimension focuses on two main questions: whether a group has publicly condemned the military coup and whether a group has endorsed or supported the coalitions that stake a claim to the legacy of the democratically elected government deposed by the coup. These coalitions are the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), and National Unity Government (NUG). Whether a group has publicly met with military delegates since the coup is another point of analysis.

The military dimension emphasises whether a group has ongoing clashes with the military and whether these clashes are minor (threats and infrequent clashes between ground troops), or major, where clashes involved multiple offensives, seizure of military posts, artillery and airstrikes.

Mapping of the EAOs’ positions indicates that their positions can be broadly divided into four categories. There are: groups that are in open armed conflict with the military; groups that condemned the coup publicly but are reluctant to endorse military means; groups that want to take advantage of a military that is overstretched by domestic and international pressure; and groups that maintain the status quo by remaining silent. However, it is important to note that due to the rapidly changing political situation, some groups’ stances may shift overnight—but not significantly.

The two-dimensional analysis suggests that the coup has deepened the EAOs disunity despite the widespread public expectation that it would unite different forces facing a common enemy and enable the formation of a federal army. EAOs responses toward the coup and post-coup stances no longer depend on their coalition, nor on whether or not they signed the NCA. The EAO’s contradictory positions have diverged from the prospect of a new armed alliance or a federal army, which the anti-coup protesters longed for at the beginning of the coup.

Despite the joint condemnation of the coup and demand for the release of the political prisoners, members of the PPST have taken different approaches to dealing with the post-coup era. With the exception of the KNU, PPST members are avoiding armed confrontation with the military. It became obvious that there is neither strong political nor military coherence among the members of the PPST when some members reportedly attended the Armed Forces Day ceremony in Naypyidaw on 27 March, and held separate meetings with the Tatmadaw’s National Unity and Peace Coordination Committee (NUPCC) in Naypyidaw in April and May.

Members of ethnic minorities standing against the military are concentrating on institutional change, while majority Bamar NLD supporters focus on the release of party leaders and the formation of government.

Myanmar’s coup from the eyes of ethnic minorities

Similarly, the stance of the FPNCC is most ambiguous after the coup – having groups at both ends of the spectrum. While three members of the FPNCC, including the United Wa State Army (UWSA), have remained silent in the wake of the coup and maintain the status quo, fighting continues between the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the military on daily basis in the country’s north. Another three FPNCC members, also known as the Three Brotherhood Alliance, are attempting to take advantage of Tatmadaw’s stretched capacity to retake lost territory.

New ceasefire agreement or a federal army?

As before the coup, NCA signatories continue to accuse each other of violations. But it is certain that none of the signatories will declare the annulment of the historic multilateral ceasefire agreement, which has been recognised by the international community and Assembly of the Union (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw). Rather than pushing other EAOs to sign the NCA before the coup, the military will continue to use informal or biliteral ceasefire agreements in order to ease pressure on its forces, as it has been doing with the AA in Rakhine State.

However, the ongoing clashes are more likely to intensify as majority of the groups currently in talks with the military’s delegates are either groups that have not had any clashes with the military before the coup or groups that only have a handful of soldiers. The military is more likely to assert both political and military pressure on pro-NUG armed groups, regardless of their troop strength and relationships prior to the coup. In addition, the scale of the military-induced violence is pushing anti-coup protesters into armed resistance as evident in many highland areas and urban cities where protesters are taking up traditional hunting rifles, homemade firearms, and bombs against the military.

Taken together, the stance of the ethnic armed organisations over the first 100 days of the coup is neither based on previous coalitions, nor on whether or not they signed the NCA. Groups have chosen different political and military positions despite the widespread belief that the coup has unified different forces against a common enemy.

Despite the EAO’s contradictory positions—having groups at both ends of the spectrum, a federal army is not impossible in the future. The idea originated with the now-defunct United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC) comprised with fourteen EAOs during the previous military regime in February 2011. The UNFC stood as one of the strongest EAO coalitions in the history of ethnic armed resistance in Myanmar.

After the coup the role of the KIA has grown substantially, both within the coalition and in engagement with the NUG. Despite the PPST’s call to form a coalition with the non-NCA signatories, the damaged relations between its acting leader and some members of the FPNCC contest the practicality of this proposal.

The prospect of a Federal Army is most likely if the KIA and/or the KNU decide to arm and sustain the NUG-led People’s Defence Force, or if they can come together to lead the other EAOs in forming a Federal Army, regardless of their previous disagreements.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss