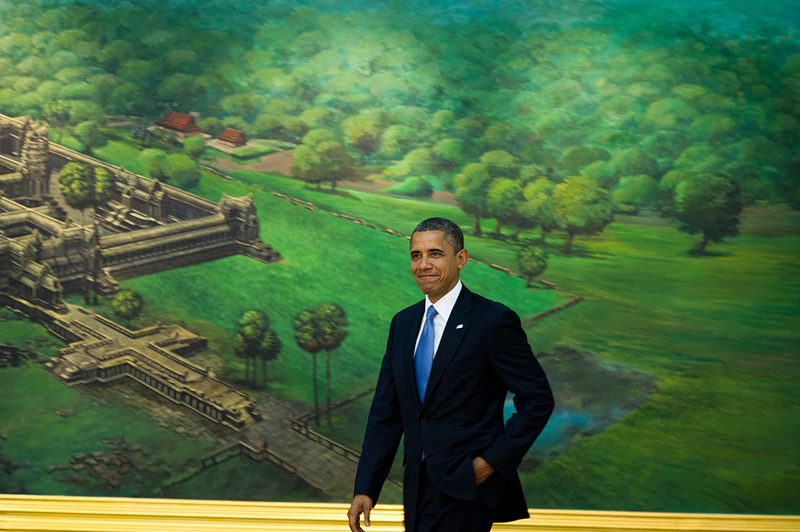

US State Department photo

President Obama just concluded visit to Southeast Asia, which has sparked considerable media comment and criticism from human rights activists. Some of them claimed that the visit sent the wrong signal to repressive governments in Myanmar and Cambodia.

In Myanmar, the visit was designed to highlight progress toward democratic reform made by the new nominally civilian government headed by Thein Sein since it replaced the military junta that had governed the country since 1972. Actions by the Myanmar government have included the release from house arrest of opposition activist and 1991 Nobel Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, the freeing many (but not all) political prisoners, relaxation of strict controls on the media and the holding of a largely free and fair by election to ямБll some 40 parliamentary seats rendered vacant when the incumbents were appointed to senior government positions. Most notably Aung San Suu Kyi was allowed to participate in these elections, winning a parliamentary seat and thus becoming the leader of the opposition.

These dramatic developments have won widespread praise from the international community and the US government, which has responded by relaxing economic sanctions against the military regime and sending an Ambassador to Myanmar for the ямБrst time in over twenty years. More rewards are promised if the new government continues on its current reformist course, including the release of all remaining political prisoners and opening of the country to outside investment. Obama’s visit was intended as part of this gradual tit for tat process toward democracy and openness to the outside world.

The visit was scheduled on rather short notice, it appears, because the President was making a visit to the region to attend the ASEAN and East Asia summits being held in Cambodia and it was convenient to make an additional short stop in Myanmar. Many in the human rights community have complained that the reform process in Myanmar is not yet irreversible and that leaders of the former military junta continue to lurk in the background, possibly still pulling the strings. In addition, the new constitution drafted by the generals, which guarantees military control over the parliament, remains in force and could still be invoked to bring the reform process to a halt at any time.

Furthermore, there is no indication that any of this will change before the next scheduled general election in 2015, which could thus be managed to assure a military controlled parliament similar to the one returned by the last election in 2010, which was condemned by the international community. Thus, despite much progress toward democracy, there are many remaining uncertainties about how far the reform process will go and whether it might be reversed at some point.

Despite these uncertainties, President Obama apparently decided on the Myanmar stop because this ямБts well with the administration’s pivot to Asia designed in part to balance out Chinese influence, upon which Myanmar became increasingly dependent after being shunned by the West. Myanmar is now a poster child in this new Asia focus, going so far as to halt a major hydroelectric dam project funded by the Chinese.

Myanmar’s opening is also a success story – the only one so far – in the Obama policy of reaching out to rogue states, which he announced at the beginning of the administration. The President made this point while in Yangon.

By all accounts the visit went very well, as crowds lined the streets to greet Obama and his speech at the University of Yangon (shuttered for most of the past 20 years to avoid student protests against the military government), in which he outlined his hopes for a democratic future in Myanmar, was well received. He also was able to make the now obligatory stop to visit Aung San Suu Kyi at the lakeside home where she was held in house arrest for much of the past two decades, providing a colorful photo op. How all this will stand up in the future remains to be seen, especially in light of the question marks hanging over the 2015 elections.

Uncomfortable in Cambodia

The visit to Cambodia was more complicated. During the weeks preceding the trip there was a barrage of statements by the human rights community arguing that in light of the Hun Sen government’s poor record in this regard President Obama should not go there. Human Rights Watch pointedly published a long report detailing the numerous politically related murders attributed to the regime over the past twenty years. This apparently made Obama so uncomfortable that he declared publicly that he was visiting Cambodia only because of the summit meetings being held there, in the absence of which he would not have done so.

In addition, Obama’s staff told the media that his meeting with Prime Minister Hum Sen on arrival was “tense” because he had strongly criticized the Cambodian leader for his human rights record, including forced expulsion of peasants from their land to implement development projects, intimidation, including imprisonment, of opposition leaders and other critics, and failure to conduct free and fair elections. These points seemed to track closely with charges made in a recent report by the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights for Cambodia.

However, such reportedly strong words were seriously weakened by the fact that Obama made no public declaration of his own on these points, leaving this entirely to his staff. A number of international media reports highlighted the so called scolding of Hun Sen on human rights but the impact in Cambodia itself was limited because there were no quotes from Obama himself to back this up. According to the media brieямБng by the Obama staff, Hun Sen defended his actions and hoped to maintain a close relationship with the US despite the Obama criticism.

In fact, over the past 20 years the Cambodian leader has become accustomed to strong statements like this by foreign leaders, followed by business as usual in terms of foreign assistance and other prerequisites. In other words he knows that there is almost never any “bite” following such “barks.” In any case, if necessary, he can fall back on aid from China, South Korea, Vietnam and others who place no conditions on their assistance and do not bother him with irritating statements on human rights or elections. He has said this publicly on many occasions.

The reality is that the US seems to want a close relationship with Cambodia more than Hun Sen does. This stems in part from the same reason that America is pursuing an opening with Myanmar – China. Cambodia is another link in the pivot to Asia strategy and the US has pursued this through naval ship visits, joint military exercises, counter terrorism training, cooperation on human trafficking and other similar areas, including the presence of a Peace Corps contingent in the country for the past ямБve years.

Although rarely stated publicly, one US concern in Cambodia seems to be possible radicalization of the Muslim Cham minority and programs have been devised to reach out to them, largely through military channels it appears. Hun Sen is a wily politician and he understands very well that, given these conditions, the US is unlikely to confront him in more than words. Meanwhile, he has been able to bask in the presence of Obama standing beside him during group photographs at the summit meetings, all displayed prominently on Cambodian TV. This is clearly a situation in which photos speak much louder than words.

Don Jameson is a retired Foreign Service Officer who worked at the US embassy in Cambodia during the early 1970s, and in Myanmar from 1990 to 1993. He speaks Khmer.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss