As a political sociologist by training, I find it interesting to analyze the local discourse on democratization processes in different transitional societies in East and Southeast Asia. I have lived in Taiwan for almost ten years and during that time I have frequently visited Thailand, South Korea, Mongolia and Japan for research purposes.

In political science there is the question of whether a transitional society succeeds in coping with the pitfalls of democratization or whether it regresses to authoritarianism. From this perspective, Thailand and other transitional societies in the region are worth studying and may help us to gain a better understanding of what policy makers could do to prevent the collapse of democratic institutions in other newly established democracies.

From my observations, South Korea has best overcome the difficulties of dealing with the pitfalls of democratic development among the new democracies of Asia, whereas other countries, especially the Philippines and to some worrisome extent Thailand and Taiwan, have put their political achievements at risk. Developments in the later two transitional societies have striking similarities, although the general settings of these two polities are fundamentally different.

In this brief photo essay, I would like to address those similarities in order to stimulate further discussions among members of the scientific community. I believe that more extensive comparative research is necessary and would benefit the global discourse on democratization and the consolidation thereof.

Emergence of unprecedented corruption

During the last few years, Thailand as well as Taiwan experienced the emergence of what is frequently termed “new democracy movements.” Growing dissatisfaction with the policies adopted by incumbent political leaders, the perceived government’s attempt to destroy the very foundations of the state, and the wide-spread perception of unprecedented corruption and misuse of state authority sparked off anti-government demonstrations and debates about the apparent shortcomings of democratic elections.

In Taiwan, Chen Shui-bian has been the prime target of the self-proclaimed new democracy movement since his presidential inauguration in 2000. In Thailand, the protectors of democracy targeted Thaksin Shinawatra for about the same period of time. The accusations are strikingly similar and so is the (academic) discourse.

The protectors of democracy and the right to kill opponents

At the height of the local discourse, the protectors of democracy raised two fundamental questions: First, is a comparison between those two leaders and Adolf Hitler justified? Second, under what circumstances is the execution of political leaders necessary and fully justifiable?

As to the first, intellectuals agreed that there is enough evidence to claim that both leaders deserve to be listed as the regional version of Adolf Hitler.

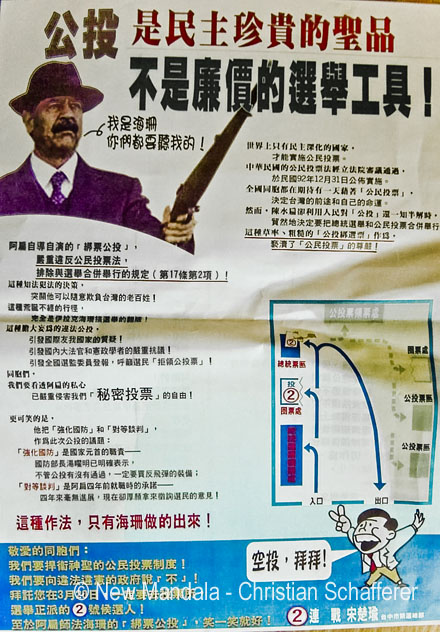

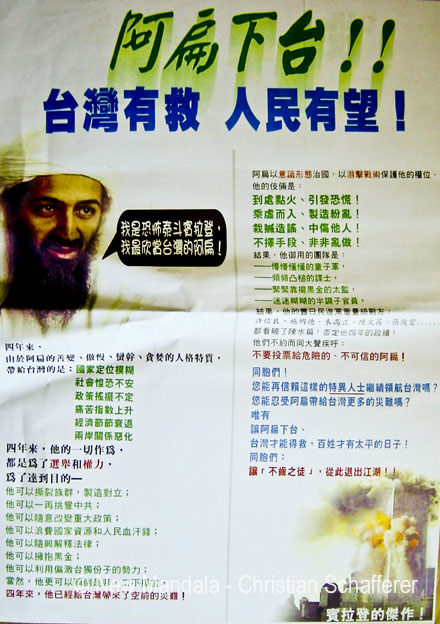

In Taiwan, the political wing of the new democracy movement distributed posters that likened President Chen Shui-bian with war criminal Saddam Hussein and terrorist Bin Laden during the 2004 presidential election. Although some people failed to comprehend what Bin Laden and Saddam Hussein had to do with President Chen Shu-bian, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) insisted that their posters were extremely inventive and refused to stop their circulation.

Image 1: Saddam Husein poster, official campaign material, presidential election, March 2004

Image 2: Bin Laden poster, official campaign material, presidential election, March 2004

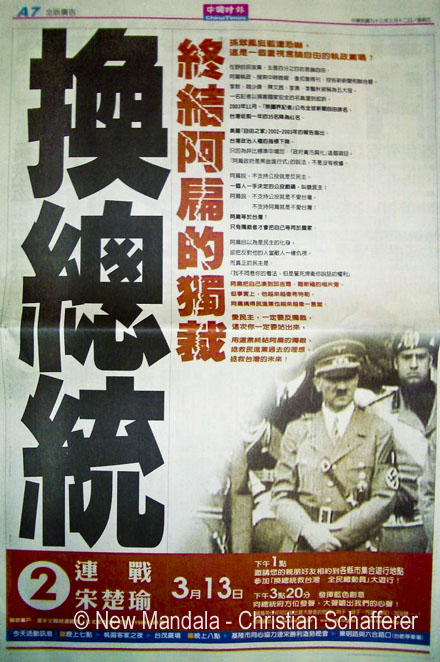

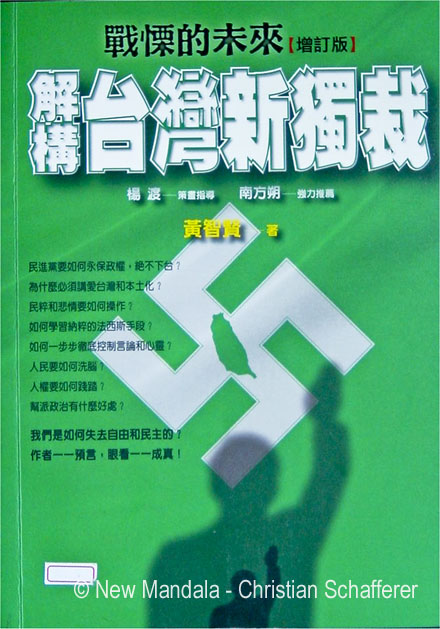

The chief campaign strategists at the KMT headquarters in Taipei considered the posters a belittlement of President Chen’s real character and decided to look for a more appropriate comparison. Soon, the people of Taiwan were taught in newspaper advertisements that President Chen Shui-bian is Taiwan’s Adolf Hitler. It did not take long and bookstores around the island were filled with publications about Hitler Chen. One of the most popular books at that time was Shuddering Future: Dismantle Taiwan’s New Dictatorship.

Image 3: Hitler Chen ad in leading newspapers, March 2004

Image 4: Cover of popular Hitler-Chen book, 2004

In Thailand, PAD protestors distributed pamphlets depicting Thaksin as the Thai version of Hitler, who forced his fellow citizens to raise their arms to the Nazi salute. More recently, artwork likening the activists’ enemy to Saddam Hussein and Adolf Hitler could be seen on the newly occupied territory of the PAD.

Image 5: Reincarnation of Adolf Hitler, pamphlet distributed during PAD rallies (Source: Srithanonchai)

Image 5a: Reincarnation of Adolf Hitler, picture posted on website of influential Thai NGO (Source: Srithanonchai)

Image 6: Reincarnation of Saddam Hussein and Adolf Hitler, PAD territory, 26 September 2008

As to the second question whether one has the right to kill a dictator like Thaksin or Chen. Intellectuals in both countries answered this question in the affirmative.

In Thailand, supporters of the new democracy movement openly called for the execution of Thaksin, whereas other influential activists also wanted to see Thaksin’s daughter become a whore infected with venereal diseases. During my last visit to the PAD occupied territory, death wishes against the opponents are still in evidence among the protectors of justice.

Image 7: Political opponent hanged, PAD territory, 26 September 2008

In Taiwan, the leader of the political wing of the new democracy movement openly declared Chen Shui-bian an outlaw who should be hunted down, whereas other intellectuals, especially one outspoken law (!) professor of the prestigious National Taiwan University, repeatedly demanded the death penalty.

Emergence of new democracy movements and markets

In 2006, Taiwan’s new democracy movement gained new momentum. President Chen’s wife was accused of corruption and his son-in-law of insider trading. Shi Ming-de, a former victim of the KMT dictatorship, called on the people of Taiwan to wear red shirts to symbolize disapproval of Chen Shui-bian. Soon, the red movement covered the streets of Taipei. Shi’s revolutionary speech lasted for a mere 5 minutes, repeatedly claiming that Chen was corrupt and should step down immediately. Despite the disappointing speech, Taipei had a new tourist attraction for the weeks to come. Buses packed with “protesters” arrived at the site of the revolution, especially on weekends. The streets of Taipei were crowded with yelling people and making thumbs-down gestures. The media spoke of a great moment in the nation’s history. Justice would come soon; the unscrupulous, ferocious, corrupt president would soon be gone. The period of the Red Movement was a time of enormous intellectual discourse. University professors dressed in red showed their unlimited support for the new leader, the protector of democracy.

Why not be part of a revolution? After all, participants could enjoy artistic performances while sharing free food and drinks. Everybody was curious to find out what would be next on the programme. Not only artists could perform there, intellectuals from all walks of life could express their opinion. Students joined the programme, too. Some of them repeated their leader’s opinion that Chen was corrupt and should step down. Others were more intellectual and rephrased songs and poems. All of them were extremely excited because they were live on TV. They were the heroes of a great revolution. The world would remember them as the true fighters for justice and democracy. It was simply in vogue to be on TV and to attack Chen Shui-bian. Even primary school kids learned their anti-Chen poems and presented them at school or on TV. T-shirts, banners, books, cups and other merchandise were sold as souvenirs. Photos were taken so that the participants could prove with pride to future generations that they defended democracy at high personal risks. It did not take long before media reports referred to the protests as the “carnival in Taipei.”

When I visited the PAD’s newly occupied territory around Government House in Bangkok, many things seemed familiar. Brand-new expensive cars parking around and inside the territory, kids voicing their concerns, abundant souvenirs, free food, and the sale of products that nobody would seriously associate with a revolution.

Image 8: Street market, PAD occupied territory, 26 September 2008

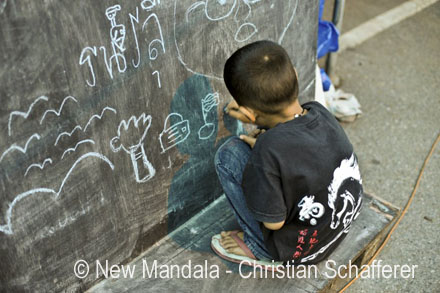

Image 9: A concerned young activist expressing his opinion, PAD territory, 26 September 2008

Image 10: Another concerned young activist expressing his opinion, PAD territory, 26 September 2008

Image 11: A revolutionary designing shopping bags for the PAD night market, PAD territory, 26 September 2008

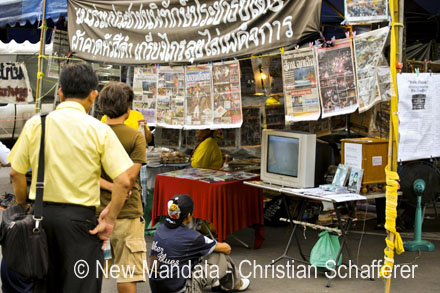

The PAD occupied territory looks more like a market than a place where serious social and political issues are discussed. Remove the English protest signs, and the PAD occupied territory easily sells as a new tourist spot besides the floating market and other attractions in Bangkok. They offer bags, T-shirts, CDs and framed photographs featuring famous people and historic events, such as the 1976 Thammasat Massacre and the 1992 anti-government demonstrations.

Image 12: Sale of plastic hand clapping tools for the revolution, PAD night market, 26 September 2008

Image 13: Sale of food, bags, shoes and other tools for the revolution, PAD night market, 26 September 2008

Image 14: A king-loving woman selling items featuring Che Guevara, PAD night market, 26 September 2008

Image 15: A Thailand-loving woman selling boot scrapers featuring the enemies, PAD night market, 26 September 2008

Image 16: A Bob Marley activist selling souvenirs featuring the revolution, PAD night market, 26 September 2008

Image 17: Information booth exhibiting and selling documentaries of this and previous revolutions. PAD night market, 26 September 2008

Image 18: Special collections of modern Thai soap operas. PAD night market, 26 September 2008

For the younger visitors, cosmetics and other commodities, such as milk powder and instant coffee are available for sale.

Image 19: A young activist buying cosmetics for the revolution, PAD night market, 26 September 2008

Image 20: Condensed milk and instant coffee for the revolution, PAD night market, 26 September 2008

In case you get lost on the PAD occupied territory, free tour guides are available.

Image 21: PAD tour guides, PAD night market, 26 September 2008

Moreover, there are live performances featuring concerned democracy activists reading poetry and novels, and of course presentations of new PAD products. And for those who want to stay overnight free accommodation is also available.

Image 22: Concerned upper-class citizens attending the PAD Friday night show, PAD night market, 26 September 2008

Image 23: One of the keynote speakers at the PAD Friday night show, PAD night market, 26 September 2008

Image 24: The same keynote speaker signing autographs and chatting with fans, PAD night market, 26 September 2008

Image 25: New product presentation at the at the PAD Friday night show, PAD night market, 26 September 2008

Image 26: Free accommodation available, PAD occupied territory, 28 September 2008

Image 27: WC facilities, PAD occupied territory, 28 September 2008

The new tourist spot is already famous, visitors travel long distances to get hard evidence of their active participation in the revolution.

Image 28: Young part-time activists taking pictures together with a PAD veteran, PAD occupied territory, 26 September 2008

Image 29: Tourists taking pictures, PAD occupied territory, 28 September 2008

While walking through the PAD territory, I could not but notice that most participants were middle-aged women. When I told one of the PAD supporters about my observation, he noted that PAD defends women’s rights and seeks gender equality. Asked whether this equality was also represented in the composition of PAD’s leadership, the supporter started to talk about the injustices Thaksin and his followers had imposed upon the poor people of the country.

On the PAD territory, I also saw a branch office of the Young PAD. One of the students talked to me in English and I asked him why he had joined the movement. He responded by saying that in Thailand few people were rich and the rich controlled the political and social lives of the masses. At the same time, one of his colleagues arrived in a brand new car.

Image 30: Youth division of the revolutionaries, PAD occupied territory, 26 September 2008

Image 31: Car of a Young-PAD functionary parking outside the Young PAD branch office on PAD occupied territory, 26 September 2008

In Taiwan, I have hardly heard that a student joined the movement out of his concern over the poor. They would usually tell me that their borough chief or some other politician offered them NT$ 2,000 (US$ 60) for taking a weekend trip to the carnival in Taipei.

What’s the difference?

Street protests and the call for justice are nothing new. They have occurred numerous times in Thailand as well as in Taiwan. So, why should the so-called new democracy movements be classified as mob rule and be considered a threat to the future development of democratic institutions in the region?

In the past, the opposition took to the streets, sometimes with violence, just like the participants of the new democracy movements. In this respect both generations of democracy activists share similarities. But that is the only thing they have in common. Everything else was fundamentally different to what the situation is in today’s Thailand or Taiwan.

During the martial law period in Taiwan, there were great injustices. Political opponents were imprisoned, tortured and many disappeared. The media was strictly controlled and publications critical about the regime were banned. There was no opportunity for the opposition to address their issues of concern publicly without facing dire consequences. The political system was de-facto authoritarian with gross human rights violations. The concerns of the democracy activists were more than justified. I do not see the existence of such a situation in today’s Thailand or Taiwan, though. They do not have to fear about their personal safety, when they speak out against their opponents. In addition, they do have legal means of communication. When I started to do comparative research on Taiwan’s democracy movements there was one critical difference I noticed. Previous movements not only addressed injustices but they also tried to communicate with ordinary people and what is even more important they looked for ways to help the people overcome their social difficulties and to defend their rights. At the end of the 1970s, for example, democracy activists set up legal counseling offices around the island, where workers and others affected by the government’s policies could get free legal advice and other practical help. University professors were invited to give lectures on what is wrong with the current policies and what could be done to overcome these difficulties. There was a meaningful intellectual discourse, which brought about many powerful social movements in the late 1980s. These movements in turn made incumbent governments aware of the need for new legislation improving the rights of the people.

The new democracy movements, on the other hand, have abundant ways to deal with their concerns, but they do not make use of them. Today’s activists voice their concern about the widespread corruption of Thaksin, Chen Shui-bian and their followers. They believe that once they have toppled those “criminals,” their country will be freed from corruption and injustices. But, are they really concerned about corruption? What steps have they taken to fight corruption in their countries? How many seminars on corruption prevention has the intellectual wing of the new movements organized? How many local initiatives have there been? How many legislative drafts has the political wing of the movements submitted to parliament for discussion?

Instead of seeking feasible and meaningful solutions, they are opposed to any conversation with their critics. They have opted for isolation and unnecessary violence. Critics are simply condemned and vowed to be replaced. The creation of the Ratchadumnoen University serves as an example here. Academics critical of their approach were declared incompetent. The new democracy activists ascertain that only those who joined their protests at Ratchadumnoen Nok Avenue are qualified to speak about democracy, Thailand and the people.

Image 32: PhD diploma signed by PAD leaders and authorizing people to speak about democracy, available for 100 Baht at PAD night market, 26 September 2008

The new democracy movements have failed to practice democracy; they have just consumed it. And that is why the movements constitute a threat to the future development of democracy and humanity in the region. In the early 1990s, the global academic discourse focused on the question of whether democracy is a universal value or whether there should be regional interpretations of what democracy is and what not.

The new democracy movements in Thailand and Taiwan are likely to be used in the near future to back up the so-called Asian values theory, which will seriously endanger human development in the region.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss