Malaysia’s 14th general elections (GE14) will see an intense and dynamic battle for the Malay electorate, but also continuity of the extensive, embedded, and often misconstrued, pro-Malay ethnic preferential regime.

Tapping into widespread economic discontent and anxiety, particularly in the Malay population, incumbent Barisan Nasional (BN) and opposition Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalitions both offer populist-flavoured menus, with varying signature dishes. BN will try to differentiate itself by drawing attention and emotion to the pro-Malay, and more broadly pro-Bumiputera, policies that it founded and continually implements.

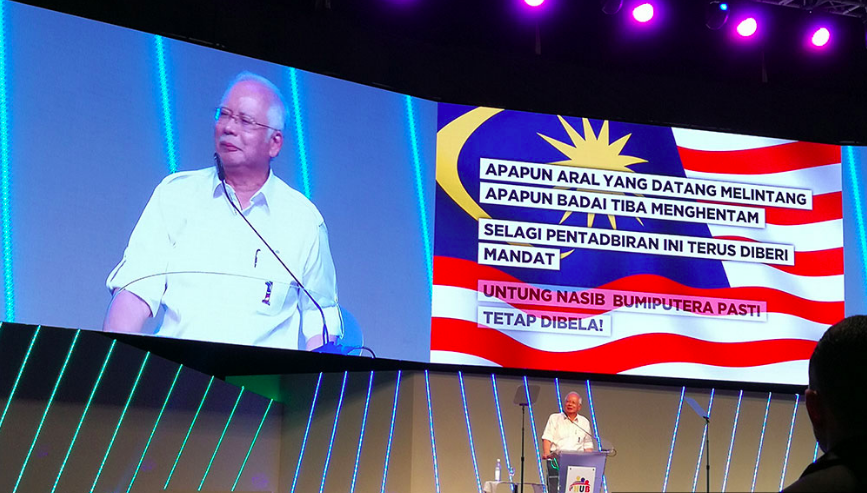

The political rhetoric around Bumiputera policies will escalate in the coming weeks – and recycle simplistic and convenient stances. With polling day set for 9 May, the BN under the hegemony of UMNO and dependent on Malay vote bases, increasingly kindles notions of Malay unity and Malay interests, and stokes anxieties of purported erosion of ethnic primacy and privilege. Expect caretaker prime minister Najib Razak to sell the Bumiputera Economic Transformation Programme (BETR) as a big deal, and seek a mandate to stay the course.

But the policy may not make that much of a difference; PH broadly agrees with keeping this ethnic preferential system. The newly reconstituted coalition, with a Malay-based party led by former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad, decidedly affirms the goal of Bumiputera empowerment. It minimally specifies how its approach differs from BN’s. Assuredly, as happened prior to the 2013 elections, Pakatan will decry the patronage and cronyism recurrent in various Bumiputera-favouring programmes, while taking care to avoid alienating the multitudes that benefit from the policy, as we can discern from its alternative budget.

Thus, Malaysia’s Bumiputera preferential regime muddles along. Both coalitions have mellowed their stance compared to a few years ago, when there was more forthright talk of replacing Bumiputera preferential programmes, also termed race-based affirmative action, with “need-based” and “merit-based” affirmative action. Now the discourses imply all the above vaguely coexist, while occasionally accepting that perpetual ethnic preference is undesirable.

Clarity and precision are urgently needed, presenting coherent policy alternatives and workable solutions anchored to the objective of promoting Bumiputera participation in higher education, high-level occupations, enterprise and ownership. Policy objectives and instruments must be acknowledged, their breadth and depth grasped.

A systematic and viable roadmap for phasing out the existing Bumiputera preferential regime must lay the groundwork by broadly cultivating capability, competitiveness, and confidence. The different policy spheres also present different conditions. Higher education holds out a broad scope for “need-based” assistance for the poor and disadvantaged, through admissions policies, scholarships and financial assistance. For Bumiputera empowerment in employment and enterprise, “merit” considerations are paramount. The principal objective in these spheres is the cultivation of capable and competitive professionals, managers and enterprises – who are poised to graduate out of preferential assistance.

So-called needs-based and merit-based selections serve to complement and reinforce the Bumiputera preferential regime. Pronouncements to replace or systematically reform race-based affirmative action with such alternatives are premature and misplaced, lacking in systematic analysis. Emphatically, Bumiputera empowerment must be effective and broad-based before systemic reforms can take shape credibly and feasibly.

The regime has registered substantial achievements in promoting Bumiputera upward mobility, but shortcomings remain in terms of the ultimate goals of capability and competitiveness. By 2013, 28.4% of the Bumiputera labour force had acquired tertiary educational qualifications, compared to 26.6% of Chinese and 25.8% of Indians. However, graduate unemployment is a more acute problem among Bumiputeras.

The Bumiputera share of managers steadily rose to 45% in 2013, from 24% in 1970 to 35% in 1985. The public sector and government-linked companies considerably contribute to these figures, and among private enterprises, micro and small-scale establishments. In 2015, among Bumiputera SMEs, 88% were classified as micro, 11% small, and only 1% medium, while the corresponding figures in non-Bumiputera SMEs were 70%, 26%, and 4%. Bumiputera-controlled companies account for only 25% of the 800,000 registered companies in Malaysia.

The Bumiputera population at large must be adequately equipped before Malaysia can truly reform and roll back the system. As things stand, there is scant analysis of policy outcomes and mostly tacit acknowledgement of policy inefficacies, and no formulation of exit strategies for facilitating the graduation of Bumiputeras out of overt ethnic preferential treatment.

To be fair, the BETR, introduced in 2011, does modify policy objectives and methods. It is distinguishable from preceding policies, through the ways it reaches out to disadvantaged students and strives to cultivate capability and competitiveness in private enterprise. But these interventions are selective, not systemic. They leave swathes of the ethnic preferential regime untouched.

Indeed, the policy spheres with extensive outreach and potential to empower Bumiputeras – in pre-university programmes, university admissions, government contracting, microfinance and public sector employment – scarcely appear in long-term development plans. There is no commitment to apply lessons from the BETR’s focused interventions, let alone any intention to execute systemic reforms.

And yet Malaysia arrives at an historical juncture, with GE14 determining who governs into 2020, the nation’s hallowed destination. Articulated by Dr Mahathir in 1991, Vision 2020 loftily aspired for Malaysia to be a “fully developed nation” economically, socially, politically, and culturally. More specific aims include the “creation of an economically resilient and fully competitive Bumiputera community so as to be on par with the non-Bumiputera community.”

Vision 2020, charismatic albeit flawed especially in neglecting education, enterprise development and democratisation, secured a place in the hearts and minds of Malaysians. So firm is the hold on the public imagination that even as the Vision’s progenitor Mahathir now assails Najib, the latter cannot forsake the brainchild of his new nemesis. Rather, Najib postures his administration as building on Vision 2020, merely implying there is some incompleteness in Mahathir’s treatise.

Beyond 2020, a new 30-year mission is being crafted under the TN50 (National Transformation) banner. This project adopts a more “bottom up” approach of compiling popular aspirations and engaging in public consultations. The templates and priorities already laid out are wide-ranging, sanguine and opportune – but conspicuously steer clear of the question of ethnic preferential policies.

It has to be acknowledged that reforming Bumiputera policies is a colossal project, and the bi-partisan reluctance to deal with it partly stems from a desire to look beyond ethnic identity and to pursue non-ethnically delineated policies. But the political consensus, while striving to transcend ethnic policies in rhetoric, misconstrues and ignores the embedded ethnic preferential regime.

Resistance to change is often blamed on the political establishment, but this is too simplistic. On the ground, societal forces are also deeply apprehensive and resistant to change. Bumiputera households are not simply being played by politicians; they materially benefit from the policies. Why and how would any people rationally, willingly surrender privilege? There are no easy answers. But Malaysia’s political dispositions and policy discourses preclude candid, honest and rigorous engagement on these crucial issues.

Election campaigns will deservedly dwell on livelihood concerns such as cost of living, social assistance, housing and jobs, and developmental concerns like infrastructure, transportation, education and health provisions, and matters of governance and morality, including social justice, inequality and corruption.

Of course, politicians will stick to simple and straightforward promises, not complex and nuanced propositions. Consistently, candid and critical discourses appear neither during elections, when new visions and mandates might be projected, nor between elections, when necessary but inconvenient reforms might be pursued. For example, in making pre-university matriculation programmes more rigorous to better prepare university entrants, or in imposing greater demands and incentives for government contractors to raise work quality and scale up operations.

However, any grand quest to take Malaysia to the next stage must address the current state and future prospects of the Bumiputera preferential regime. Instead of suppressing such questions, or entertaining misguided notions that full-fledged transformation is already in progress, a true mark of Malaysia’s progress on this issue will be its capacity to appraise how effective it has been in promoting Bumiputera empowerment, while rekindling the intent – and audacity – expressed in the past for pursuing capability, competitiveness and self-reliance.

(published in collaboration with RISE: T.wai)

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss