Did the Internet predict the Indonesian election results, asks Ross Tapsell.

“I was wrong. The media was wrong. The polls were wrong.”

So wrote veteran Indonesian political analyst Wimar Witoelar, after the Indonesian legislative elections resulted in the vote for PDI-P reaching just over 19 per cent.

The nomination of Jokowi as PDI-P presidential candidate in March was supposed to enable his party to gain well over 20 per cent of the vote. In some experimental polls, IndoBarometer thought PDI-P would gain over 35 per cent, while CSIS March polling predicted PDI-P would gain around 33 per cent of the vote.

Could Paul the Octopus have done a better job in predicting the elections than some of Indonesia’s polling companies?

For around a century, methods of political polling have been based around surveying a random sample of adults, usually highly targeted and well defined, asking them who they would vote for. It’s worth highlighting that polling figures aren’t just space filler for the media.

In any electoral democracy, political parties spend millions of dollars to gain an idea of who is ‘leading’ the polls and what issues would affect voters to sway from one candidate to another. Twenty-first century polling has become increasingly pervasive in political decision-making. In Australia, despite winning the election in 2007, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd was ousted by his party in 2010 in part because he was seen to be underperforming in all the polls. In the Indonesian election, Jokowi’s significant dominance in all the polls led the PDI-P to choose him as Presidential candidate, despite being relatively ‘green’ as a national figure and not from the elite party cadre.

Tom Pepinsky sensibly explains that polls have margins of error and “are not censuses”. As he explains, the margins of error are rarely reported. In the wash up of the elections, the main story has been why PDI-P failed to gain this predicted vote. Jokowi has been forced to answer questions about this ‘disappointing’ result. Certainly, the problem is more to do with how the polls are being read. But leading pollster Burhanuddin Muhtadi wrote that “Jokowi fell back to earth”, perhaps it is the pollsters themselves that have received the biggest reality check after the recent legislative elections.

While polls are not censuses, it is worth exploring if one polling group is closer to the actual result than some of the others.

Enter “digital democracy”; a new form of predicting elections based around the idea that, overall, what people say on the Internet is actually a very reliable indicator of how they will vote.

Skeptical? Join the club.

But read on, because in Indonesia, a new company which uses this method is making ‘waves’ in Indonesia.

‘Politcawave’ (www.politicawave.com) was established in and bases its results on millions of data generated from almost 400 online news sources (such as Detik.com, VivaNews.com, Kompas.Com etc) as well as conversations on social media platforms Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Kaskus, DetikForum and many more. It puts all this data together through an advanced algorithm to predict election results. There are no additional questionnaires nor sampling as done by traditional surveys – it’s all based on ‘big data’ from the Internet.

Over 44 million Indonesians have a Facebook account, the fourth highest amount by country in the world, while Jakarta is considered the world’s most ‘active’ Twitter city. Politcawave is taking advantage of all this data to predict the result of Indonesia’s elections.

It claims to have correctly predicted eight out of ten regional elections (or pilkada) prior to the legislative elections. During the 2012 Jakarta Governor election, they were remarkably accurate. The new Jakarta governor, Joko Widodo, now likely the next Indonesian President, apparently spent two hours with them in the aftermath of his victory, wanting to know how they whole system worked and if he could use it to his advantage.

For the legislative elections, Politicawave predicted PDI-P would gain 24 per cent of votes, less than almost all other traditional polling companies. Yet their prediction of PDI-P was still higher. Director Sony Subrata says this was “probably because there was an element of hype, because after all there was a Jokowi element in the conversations in social media”. He adds that when they announced the predicted figure of 24 per cent in the week before the election, “many of our pollster friends said that our prediction was too low”.

While there are many questions surrounding the reliability of this new method, recent Indonesian legislative elections seem to have reinforced the advantages of predicting election results through analysing ‘big data’. So, does this mark the end of traditional polling companies?

Using and analysing ‘big data’ is a burgeoning new method of polling. In the US, researchers have used Twitter to examine the trends in a political race and claim that “in the future, you will not need a polling organisation to understand how your elected representative will fare at the ballot box. Instead, all you will need is an app on your phone.”

Malaysian organisation Politweet (www.politweet.org) is using social media and the 2013 election results to try and gauge what direction the electorate is heading. In the 2008 Malaysian General election there were 800,000 Facebook and 3,429 Twitter users. By 2013 these numbers had increased to 13,220,000 for Facebook and over 2,000,000 Twitter users. In short, as these numbers grow, the reliability of the data increases.

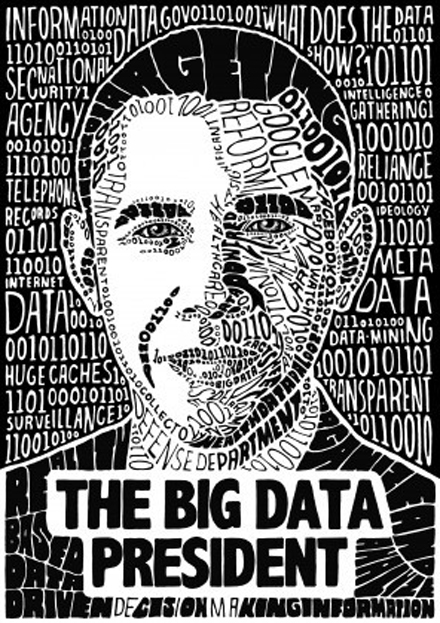

Barack Obama has been described as ‘The big data President’. Will Jokowi follow suit? Jokowi is very much a ‘numbers man’ – staff in the Jakarta Governor’s office give him daily reports on what is being said in social media. (Image credit Sarah A King for The Washington Post).

But it’s not just niche market entrepreneurial companies that are testing the water. Google now has a ‘politics & elections’ page, including for Indonesia. Check out the ‘trends’ link and ponder how eventually Google will use this information to adequately predict elections. In the current Indian elections, global companies Ebay and CNN are partnering with Indian media IBN and examining social media data.

It’s easy to overestimate the impact digital media will have in shaping our lives and in creating political change, but don’t underestimate the potential for Internet data to transform traditional ways we collected information. Earlier this month, Newsweek ran a piece stating: “Banks are about to get blown up because they don’t realize that data, not money, is their most valuable asset”.

Internet and tech companies in Asia are going into banking because by finding precise algorithms to analyse their increasing data they can know more about their users than banks, particularly in developing countries where a person’s credit history is not always clear.

If ‘big data’ companies are threatening the banks, do we really expect that traditional polling and survey companies will be exempt from this technological change? Of course not.

There will always be a place for political analysts and political scientists, not least because these people do more than just predict election results.

At present, people are still needed to analyse data to make sure various forms of manipulation, such as “fake” Twitter accounts, are not used. But as Subrata says: “PoliticaWave’s algorithm becomes smarter and smarter as it is tried and tested time and again”.

Perhaps the ‘polls’ in the 2019 Indonesian legislative elections will be analysing results solely through these methods. It would seem “digital democracy” is here to stay.

………

Dr Ross Tapsell is a lecturer in Asian Studies at The Australian National University’s College of Asia and the Pacific. He researches the media in Indonesia and Malaysia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss