This submission was written by an anonymous contributor to New Mandala.

In August I took a weekend trip to Narathiwat and Pattani to do research for a piece I am writing. I stayed in Narathiwat and Pattani city and ventured into villages for two brief stops. I am a consultant by trade but have done field social research and written articles during my career. I am a conversational Thai speaker and have spent time living in Thai villages. I have put together three separate posts for New Mandala in the hope that it will paint a picture of the people and the places that are so often in the news. This series of posts are meant only as observations – readers can draw their own conclusions.

On Security

I am not an expert on military matters but believe explaining some casual observations from my trip will elucidate some of the trends that drive the larger security issues in the south. For detailed explanations of militia and military issues in Thailand I highly recommend reading Desmond Ball and David Scott Mathieson’s Milita Redux.

Video I took of military units responding to a village roadside killing are posted on Youtube (Warning: Viewers may find this scene distressing):

Although I expected a heavy military and police presence in Narathiwat and Pattani I was immediately surprised at the extent and variety of soldiers in the Deep South. In Narathiwat I met and spoke with volunteer forces, the Queen’s special guard, normal enlisted soldiers called down from Krabi, and numerous local militias with various colored bandanas indicating their units. Some of the soldiers I spoke with were in Narathiwat on special duty for the visits of Queen Sirikit and Prime Minister Surayud. Indeed numerous locals told me that the number of troops had increased because of their visits.

Most soldiers seemed relaxed while on the job while one soldier expressed his unease on as we waited to get off the plane in Narathiwat. All smiles, he looked straight at me and said “This place is scary, better to be back home”.

The only airline that flies to Narathiwat is Air Asia and my flight was 80% full. During arrival and departure the Narathiwat airport terminal is full of soldiers in various uniforms. The best outfitted, with grenade launching guns, body armor and helmets were waiting in pickup trucks on benches laid down lengthwise on the bed so that three soldiers would face either side of the road as they traveled. At the front of their heavily armed caravan was a Humvee, with a gun turret manned by a soldier. When I arrived another passenger got into a cream colored Mercedes – the same color and make royalty use in Bangkok – and very swiftly left the airport accompanied by the caravan. A few minutes later two Germans I met in the baggage area – the only other westerners on the plane – were loaded into a van and given a smaller military escort out of the airport. I never did learn what the Germans were doing there. After leaving the airport’s lightly armed and razor wired checkpoint I felt as nervous as I would the entire trip.

During the ride from the airport I noticed troops stationed on the side of the road every 100 meters. This reminded me of a recent trip I took in March to

I stayed at the Tanyong Hotel in downtown Narathiwat and it was buzzing with Police. Highway patrol cars (the brown and white variety) were parked in front of the hotel all day and night and when I came back very late at 2 am on my first night there were 10 police officers sitting on sofas and talking in the lobby.

It was common to see convoys of Humvees and large SUVs driving down the main streets in Narathiwat. Some major intersections had pairs of armed soldiers standing around. On my first day Surayud’s convoy drove down the main road by the Imperial Hotel. By my estimate there were 20+ vehicles each traveling 120 km/hr on the four-lane street. Most soldiers however rode on motorcycles in pairs or in the back of unmarked pickup trucks. From an inexperienced eye it was often difficult to tell who were members of the Thai Army and who were part of local militias.

The end of Friday sermons was another time of intense activity. At 1 pm there were four or five passes by a Blackhawk helicopter with its doors open and soldiers peering down below. They flew low and made sweeping loops around the town center near the mosque by the city clock tower.

As the helicopters were passing over my head I met and talked with three soldiers from Krabi led by 49 year-old Jaisbek Pramot. Pramot told me he had worked in East Timor six years ago with the U.N. “I feel much safer here” he said, “Here they set a bomb and then vanish, it’s like they don’t have bodies”.

The military presence in the sky was outdone by the Navy. There were numerous naval ships from small patrol boats to large 50+ meter ships patrolling the beach and river. One person I met said the beach had various troops driving ATVs back and forth early in the morning.

On another occasion I was interviewing the owners of a local shop that sells candles and tubs of supplies to give to Buddhist monks on the main road in Narathiwat when a white Land Rover pulled up. My friend, a local Thai journalist who was with me at the time quietly mentioned there were men standing in the middle of the street with guns. I turned around to see soldiers referred in Thai as Mahatlik laksaa phra ong (Pictured below – their eyes have been obscured per their request).

Dressed in matching Adidas jumpsuits and wearing tennis shoes and bulletproof vests; these soldiers were serious. Young and muscular, three of them hurriedly walked to the store and bought lottery tickets while one stayed on guard by the car. Friendly and talkative but withholding their names I asked them how they felt working under such dangerous conditions and one replied with a laugh “I have a vest on, everything’s fine”. Five minutes later after they arrived they loaded up in the Land Rover and drove off.

By far my most chilling experience came during my drive to Pattani. Originally we had planned on going to Pattani during the day and returning to Narathiwat at night to conduct a few interviews at a reunion for famous Prince of Songklha alumni who had returned to boost support for the university as it struggles to recruit students from other provinces.

For various reasons we were not able to get a car until late in the afternoon on Saturday. As dusk approached and we finally got the car, a few women at Pong’s Café (the local journalist restaurant and bar) where we were waiting urged us not to drive on the road. Their worries were, however, overridden by the assurances of others at the café that told us it was safe, “nothing has happened there in two years” said one patron casually. Still a parting comment from the cook at the cafe caught my ear as we left, “Beware of spikes on the road”.

Slightly spooked at the prospect of getting to Pattani and returning in time before sunset we hopped in the car and sped off, driving 150 km/hr past razor wired and sandbagged checkpoints with few or no soldiers present. Even at the Krue Sae Mosque the checkpoint had only a few soldiers sitting down behind rows of sandbags and razor wire. Even later when my friend strangely decided to drive the opposite way on the street by the mosque to allow me to get a good picture none of the soldiers showed any sign of wariness.

People drive fast between those two cities and we were expecting the trip would take an hour. Smooth and well-maintained, the road has an attractive tree lined median and small villages on either side. It was in that median that I first saw something unusual.

A car on the other side of the road was wrapped around a tree and twenty locals were standing nearby either assisting or staring at the recent wreckage. I didn’t have time to analyze the incident because we were speeding along the other side; we had no intention of stopping. Besides car accidents are very common in Thailand, I had no reason to be suspicious.

But then ten minutes later in Sai Buri, a small town twenty minutes outside of Narathiwat, we noticed a Humvee up ahead on the left side of the road with various vehicles parked and people walking around. As we slowed down to pass we noticed the body of a man who had just been shot. We quickly parked the car and walked up to the scene. Soldiers, villagers, and local militia wearing purple and red bandanas were all standing around the body, some were radioing in the license plate while others were quietly standing by.

The man, a Muslim leader from the nearby village had been shot to death approximately ten minutes earlier and his body was lying in a ditch with his motorcycle by his side. We were told that there was a possibility there was a bomb under his body and were requested after a few minutes to move away. There was seemingly no clear organization about what to do with the body and there seemed to be no immediate military response from the twenty or so uniformed soldiers. As I watched the bystanders and soldiers staring off into the nearby fields by the body I felt as though it was possible that the shooter was still there somewhere in the bushes starting at us.

We did not stay long and quickly got back into the car and sped off to Pattani. After arriving at the CS Pattani Hotel and trying to relax with a cup of their famous tea and roti we heard news that the road we just had traveled on was spiked by insurgents. Ten minutes later the cell phone lines were all shut down. I walked into the empty lobby and booked a room. I questioned myself whether the crash I had seen earlier was a normal accident or the result of spikes.

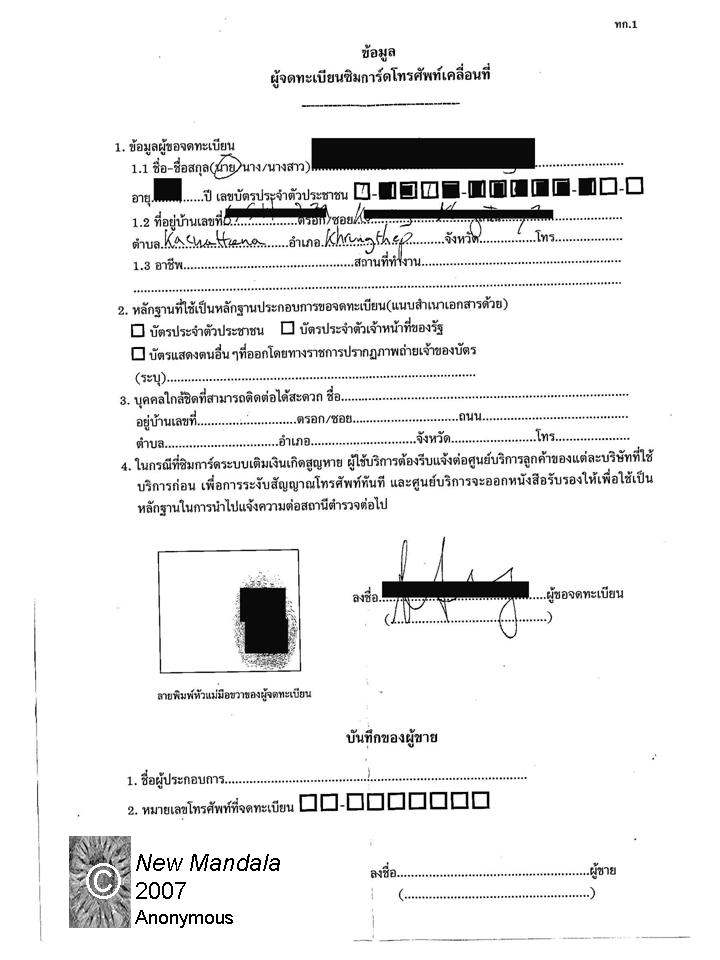

One of the main security measures the military has established in the southernmost provinces are restrictions on cell phone use. While I was able to get cell phone reception from my DTAC service after I landed, my travel companion’s AIS was immediately cut. When traveling to the Narathiwat or Pattani you must register your cell phone with your ID card and fingerprint. In my case it turned out that since I was a prepaid DTAC subscriber they already had paired my ID with my account. Insurgents almost universally use cell phones to detonate their bombs. So now the military requires all cell phones to be officially registered. When insurgents hit multiple places at one time the military will shut down all service for a period of time. On Saturday after we finished our tea the phone lines were cut. We didn’t get service until late the next morning. A picture of my cell phone registration card is below:

While the vast majority of soldiers I saw were reasonably equipped with M-16’s, I was most surprised at two soldiers in particular on my flight out on Sunday morning. One was about six feet two and very fit. He wore an earpiece, body armor, full fatigues, straps, and had a machine gun I hadn’t seen any other soldiers carrying. He stood for an hour quietly in the corner of the Narathiwat airport terminal observing the crowds. I didn’t seem him again until I felt a hand on my back while waiting at the back of the line to board the plane. He was there again with another soldier in similar fatigues and weaponry. They were escorting an elderly woman in traditional Buddhist monastic clothing to the door of the plane and politely pushed me aside to let her pass.

In summary the military presence was large, varied, and it was difficult to see clear coordination in their efforts. Soldiers and to a lesser extent some police seemed to fit into very clear hierarchies based on uniform and equipment. Their presence in the big towns was, in my observation, exponentially greater than on the roads in the rural areas. Judging by my experience seeing the shooting victim, the response time for military is fast but that could have been because the incident occurred on one of the most important and major roads in the Deep South.

With all of the traumatizing and paralyzing confusion in the Deep South surrounding exactly who and how many insurgents there are – I wonder if local people are asking the same questions of the Thai military. Both insurgents and the military seem to be everywhere and yet the outside observer can’t tell the villager from the terrorist or the trained soldier from the volunteer militia. It was the confusion and uncertainty of it all – rather than the actual fear of violence that unsettled me the most.

More photographs from my trip are posted on flickr.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss